Advertisement

Life After Hockey For Bobby Orr

Bad knees forced Bobby Orr out of the NHL in 1978 after only 12 years, but he's arguably the best who ever played: a defenseman who stayed by the net, but also soared down the ice to score.

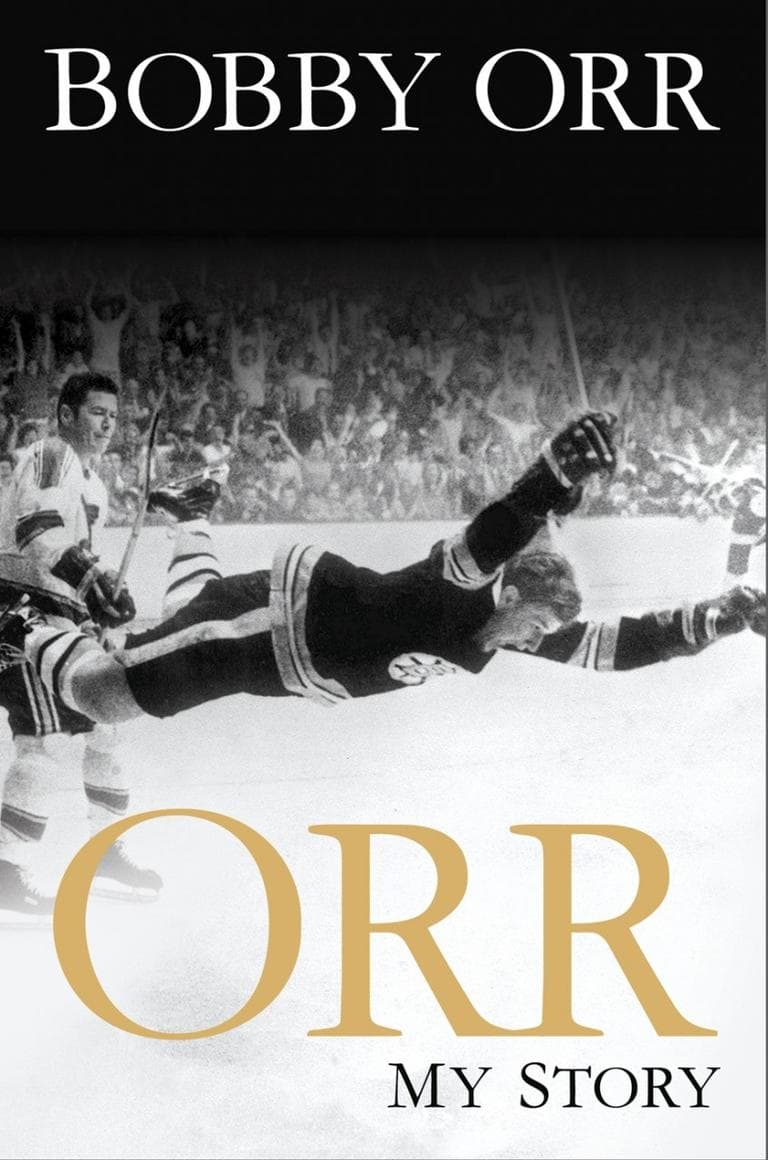

He led the Boston Bruins to two Stanley Cups including 1970 with his game-winning goal in overtime — a play immortalized in a statue outside the TD Garden based on the iconic photo of Orr flying through the air (above).

Orr’s new memoir, "Orr: My Story," tells of his career, his work with kids as an agent and as head of The Grr group.

Book Excerpt: 'Orr: My Story'

by Bobby Orr

Three: Oshawa

My hockey story is not unlike that of many kids who dream of playing in the National Hockey League, though I suppose my journey started a little bit earlier than most.

One of the hardest parts of becoming a hockey player is leaving home. Think of yourself as a fifteen- or sixteen-year-old packing a suitcase and heading off to a strange city. You end up billeted in the home of a complete stranger, attending a school you’ve never heard of. The group of friends, the pack of wolves, you’ve grown up with suddenly vanishes. The safety net of friends you’ve come to depend on is replaced by strange faces in the hallways of your new high school.

You’re playing for a new hockey team, in a huge, unfamiliar rink, being cheered or booed by people you don’t know. You’re traveling from town to town. You’ve got bigger, older guys needling you night after night, trying to get you to drop your gloves, trying to see what you’re made of. Being plucked from one place and dropped somewhere else is going to be difficult for anyone, let alone a young teenager.

Advertisement

Or, if you have children of your own, think of it from a parent’s perspective. Think of giving up a son at such a young age in order for him to pursue his goals somewhere else. That boy of yours, still just a baby in your eyes, is snatched from you and taken in by someone else. That is exactly the scenario my parents had to face, and countless other parents are confronted with the same situation at the end of every summer. I know very well just how difficult it can be for parents to see their kids go, because I was in the room when my mother wrestled with the decision over whether to let me go off to play junior hockey.

In a sense, the most remarkable thing about my rookie season in Oshawa was that it happened at all that year. I was only fourteen and hadn’t yet left elementary school, but that was a minor speed bump compared to the fact that my mother was against it. I wanted nothing more than her permission right then, and I knew from experience that cajoling and negotiating were all but useless once she’d made up her mind. So, while she was deliberating, the question of where I would play hockey in the fall of 1962 was entirely in her hands.

I hardly dared speak while my future was being discussed. But my father made my case with his usual persuasiveness, as did another gentleman who played a very important role in my career: Wren Blair.

Back when I was playing minor hockey, there was no such thing as the NHL Entry Draft. Until 1963, NHL teams could control players’ rights, even at a very young age. (In fact, the first draft was for sixteen-year-old players, and two of the six teams in the league, Detroit and Chicago, didn’t bother picking in the fourth and final round, as most sixteen-year-olds’ rights were already wrapped up.) Teams wanted to lock up the playing rights to any player who might

possibly cut it five or six years down the road, and the terms needed to retain those rights were definitely in the team’s favor. Teams could ask players to sign what was called an A Form, which committed the kid to trying out with the club; a B Form, which gave the team the right to sign the player without actually committing to him; or a C Form, which completely assigned the player’s rights to the team. Once you had signed one of these, you lost any negotiating leverage you might have had with the team. But then, players didn’t really negotiate in those days anyway. After all, there were a whole bunch of prospective players but only six teams in the league, so supply exceeded demand. Kids who dreamed of suiting up in the NHL were often all too happy to commit to a team that showed interest in them.

All the teams had “bird dogs” in minor hockey rinks across the country, appraising young talent and guaranteeing a steady supply of it. And without a draft to ensure that talent was distributed evenly across the league, there was a real advantage to getting to young players first. That’s one of the reasons the Canadiens were so consistently represented by the very best French-Canadian players. They had the best scouts in the rinks of Quebec—and they had a steady stream of young Québécois players who would give just about anything to sign a C Form with the team they grew up worshipping.

The Toronto Maple Leafs had all the glamorous appeal of the Canadiens back then. Every kid in Ontario grew up idolizing the Leafs (as I did), so the Leafs could count on a reliable supply of starryeyed young men, and an equally steady supply of tips from minor hockey rinks in far-flung towns. Parry Sound was no different.

Adapted from ORR: MY STORY by Bobby Orr, published by G.P. Putnam’s Sons, a member of The Penguin Group (USA) LLC. Copyright (c) 2013 by Robert Orr.

Guest

- Bobby Orr, former Boston Bruin and author of "Orr: My Story."

This segment aired on October 15, 2013.