Advertisement

New Horizons Mission Leader Explains Pluto's Ice Mountains And More

Resume

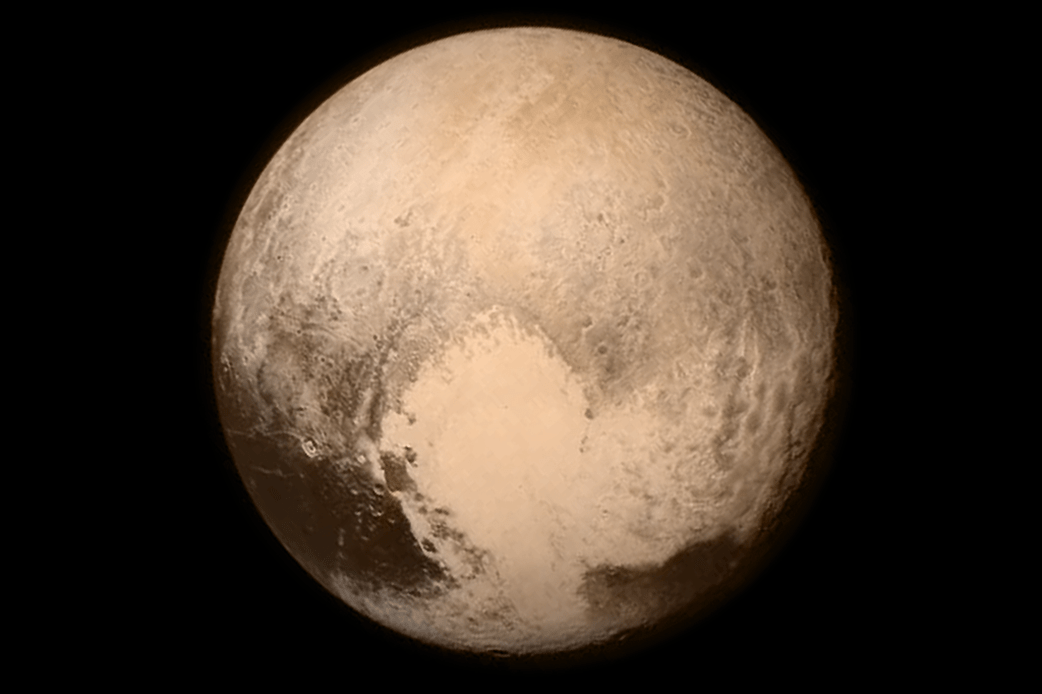

Just days after NASA's New Horizons space probe flew past its primary target Pluto, scientists are already re-writing the old planetary textbooks.

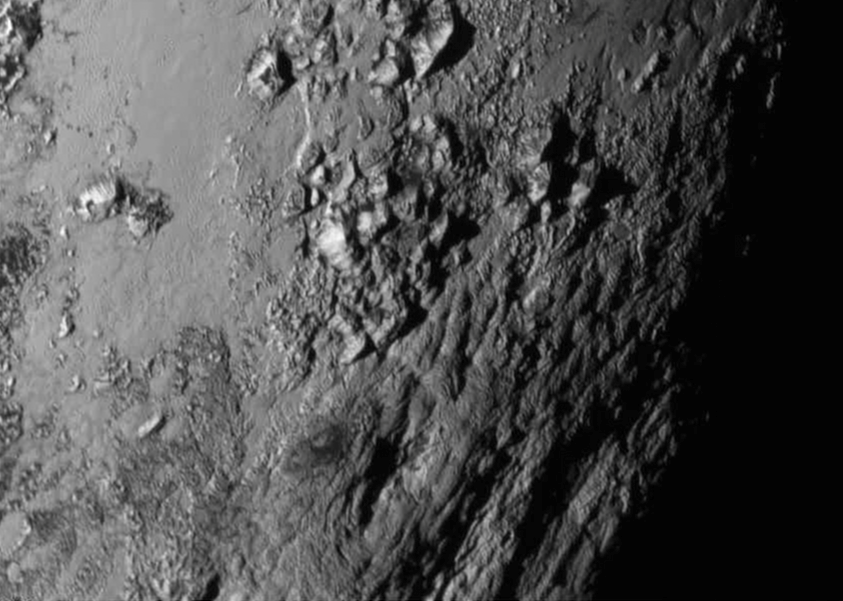

The first images from the mission have revealed ice mountains about the size of the Rockies and a surface devoid of craters. Both comes as surprises to those involved in the project and have significant implications regarding Pluto's history and make-up.

Here & Now's Jeremy Hobson speaks with New Horizons mission leader Alan Stern about the latest discoveries and what's next for the space probe.

Interview Highlights: Alan Stern

On the team's biggest discovery about Pluto (so far)

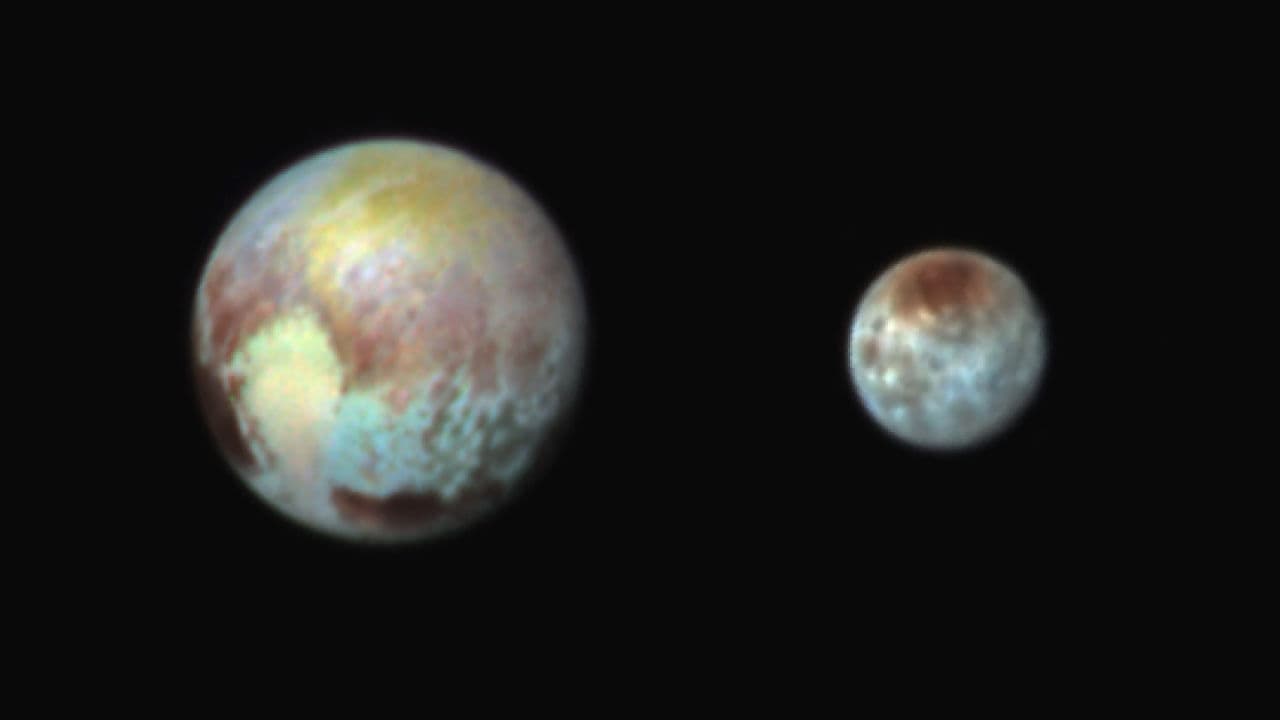

"Let me emphasize that we have very little data back, so I don't know that this will be the biggest discovery. But it is a big discovery. We discovered that Pluto and its moon Charon are still geologically active after all this time, after 4-plus billion years since they were born. That really changes some very deep-seated concepts in planetary science, because the small planets are expected to cool off in much less time than that, so they shouldn't have an energy budget that allows them to drive active geology after so much time. So our discovery, which flies in the face of that, will cause a big rethink of how planetary engines work."

Discoveries about Pluto's surface

"When we look at Pluto's surface, and measure it's composition, which we've been able to do from the Earth and from Earth orbit with instruments like the Hubble [Space Telescope], we know that the surface composition is dominated by snows of nitrogen. And it's the same stuff we're breathing right now in the air, but on Pluto, it's frozen as a snow on the surface. And the thing about nitrogen is that it's a very weak material, so just like sand or other things that we could think of as examples of weak, if you try to pile it up in a big mountain, it'll just collapse or slump under its own weight. So you can't have nitrogen mountains. So the discovery of mountains on Pluto means that the nitrogen layer is thin like a frosting on the surface, and that the substrate that lies beneath the nitrogen - which makes the mountains - much be something much stronger, and we're pretty certain it's going to turn out to be water ice."

On whether or not there could be life on Pluto

"That water ice is frozen at 400 or so degrees below zero, so not life as we know it in that ice. But down below, deep in the planet, where the heat is sufficient, the water ice could melt, and there could be a liquid ocean inside of Pluto... Even in our deep ocean there are ecosystems at work with no light whatsoever down in the deepest portions of the oceanic abyss. So light is not what's critical. What's critical is energy, but there is a source of energy deep inside planets. It's the heat from the overlying pressure burden of rock and ice above. So if it's warm enough to create liquid water, that itself is the same energy source that could ultimate power biology. Whether there's even an ocean on Pluto deep inside is a question I hope New Horizons can address in indirect ways. And then this sort of speculation about biology would be more serious."

What comes next for New Horizons?

"Our fondest hopes and wildest dreams are that we fly on further into the Kuiper Belt as the National Academy of Sciences charged this mission to do, and make a flyby of a much smaller object, something also very old but one of the building blocks of planets like Pluto that's out there. We found our target - we found multiple targets, in fact, with the Hubble Space Telescope - and the spacecraft has the fuel to do it, and it's perfectly healthy after the Pluto flyby. It has the power to do it. If we're approved to do that, then that flyby would be in about three-and-a-half years, in early 2019."

Guest

- Alan Stern, New Horizons mission leader. He tweets @AlanStern and @NewHorizons2015.

This segment aired on July 16, 2015.