Advertisement

Remembering Emmett Till And America's 'Disappeared'

You've likely heard of "the disappeared" (los desaparecidos) under 20th century dictatorships of Chile and Argentina. But what about America's disappeared? Law professors Margaret Burnham and Margaret Russell wrote about them in a recent op-ed in The New York Times.

They were referring to hundreds of black Americans killed in racial violence from 1930 to 1960 – cases that were ignored or mismanaged by a biased justice system.

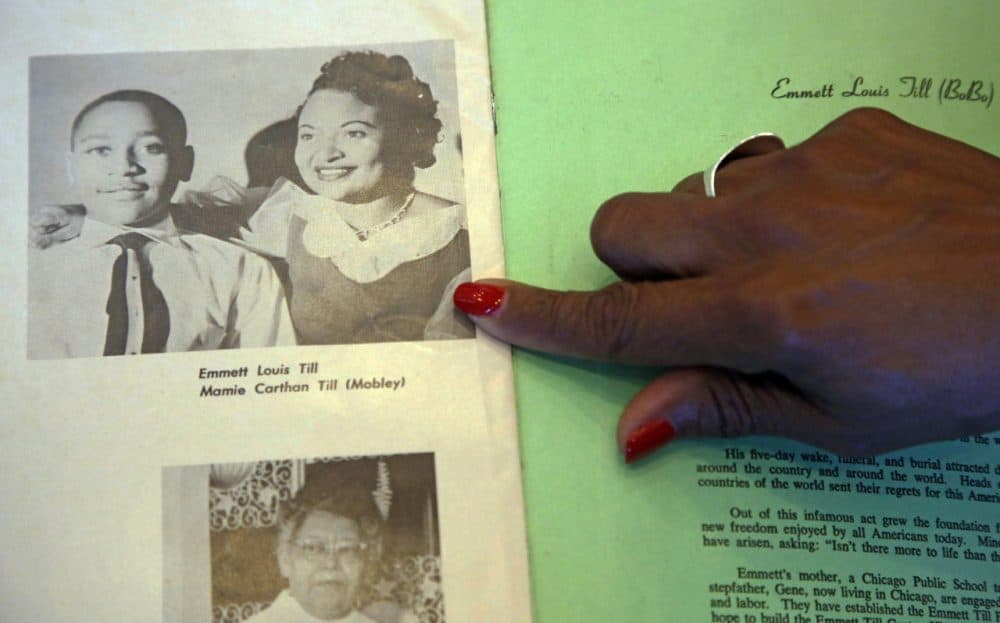

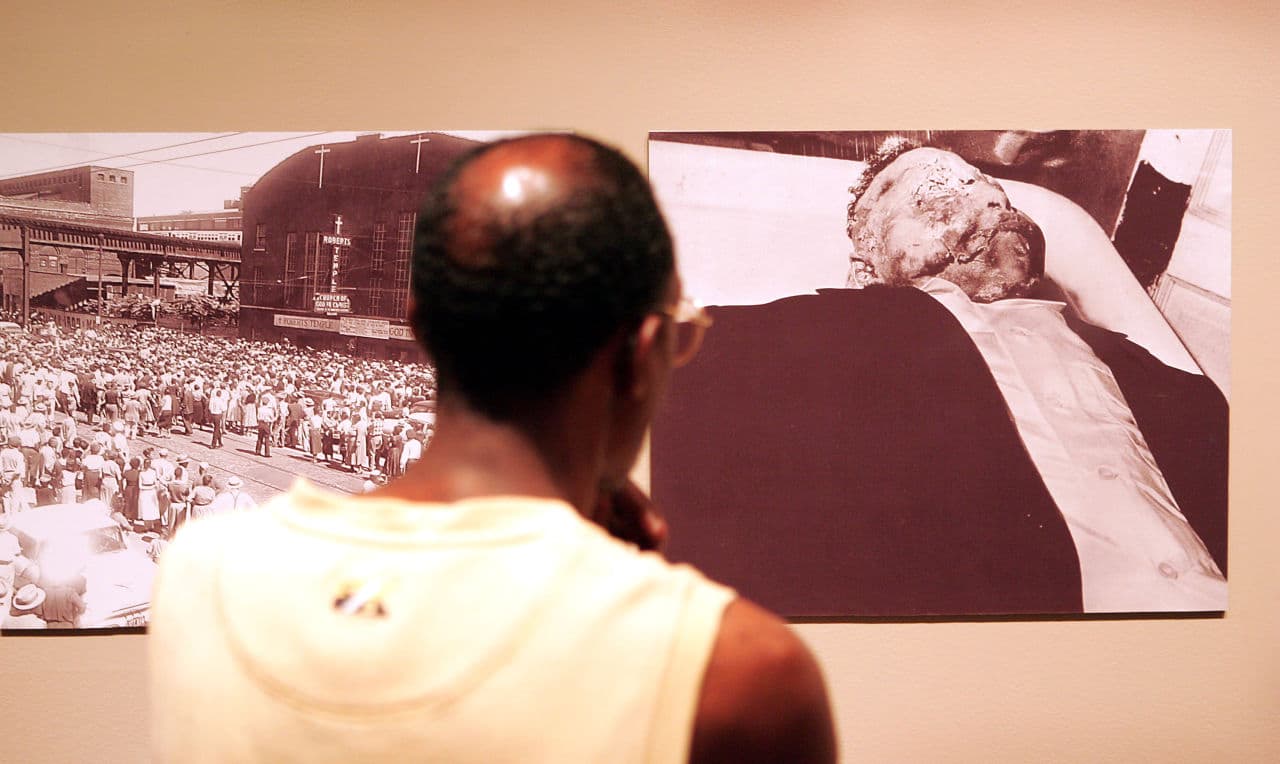

It's been 60 years since one of the most famous of these murders - Emmett Till, the 14-year-old who was pulled from his bed in Mississippi, tortured, shot and thrown in the river. His killers, who reportedly targeted him for whistling at a white woman, were let off.

Margaret Russell joins Here & Now's Robin Young to discuss her research into the Till case and others.

Interview Highlights

Why write about this now?

"What’s different now is that time is really running out. We’ve said for 25 years that time is running out to actually locate witnesses, to collect evidence. Witnesses are dying, memories are fading and evidence is disappearing. And so, over the last number of years since the federal law - the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act - passed, the emphasis has been on prosecution. I think now the realization is that fewer and fewer prosecutions can actually be brought, because of the passage of time. So our focus is on additional remedies that really look toward broader community-based, community-generated solutions that help restore a sense of justice and truth telling."

Did the passage of the 2008 Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act help?

"Yes it helped, but it didn’t go far enough. The funding did not get allocated, the members of the Justice Department who were investigating, along with the FBI, uncovered 105 files they opened, 126 victims and three prosecutions resulting in convictions. However, the law is very prosecution-focused and there are additional tools to prosecution that aren’t covered by the act. And in the collaboration that exists between local communities and law enforcement, I think we now have the opportunity to explore additional tools such as truth-telling commissions."

What do you say to people who say, 'this has nothing to do with me? I’m so removed from this, why should I be involved in commissions or reparations?'

"It’s a complex and ongoing comment. And I don’t want to disparage it, but I think we know very well from everyday events, particularly in the weeks and months since Ferguson, Missouri, that our society is suffering from very deep racial wounds. And they don’t have to do, literally, with anybody who’s not involved in Ferguson or any other city involved, but this is our country. And we have seen communities that have been ravaged over the last couple of generations because of racial hatred that really was not so long ago. Emmett Till’s death was in 1955 and I think the poverty, the segregation, the conflict between police authorities and communities, and the distrust and lack of awareness and even friendship among races in our nation is really a sign that we need to look at this more broadly and systemically."

Civil rights lawyer Bryan Stevenson has a project to note the site of every lynching in America with a marker. Do you have anything like that, are you hoping to mark it in anyway?

"As I said, teenagers were lynched, and for Ernest Greene and Charles Lange in Mississippi, they were lynched in 1942 at a place that afterwards was long called the hanging bridge - it might still be called that - but that sight is now the place for commemorative gatherings, remembering them. Another example comes from Live Oak, Florida, another teenager, a 15-year-old Willie James Howard was tossed into the Suwannee River in 1944, and now that is a marker, a site for community members to come together, not just to remember him and his life lost but what it was like in that community and to really honor the suffering of the people there."

Note: The photo below may be distressing to some viewers.

Guest

- Margaret Russell, law professor at Santa Clara University in California.

This segment aired on September 4, 2015.