Advertisement

Does Anyone In The GOP Carry Jack Kemp's Torch?

Resume

As today's Republicans struggle to broaden their base and promote reform, some are longing for Jack Kemp, the former pro football player who devoted his career to tax reform and the working class and minorities. Kemp pushed supply side economics and was really the pioneer of the ideas that helped President Reagan's economic reform of the 1980s.

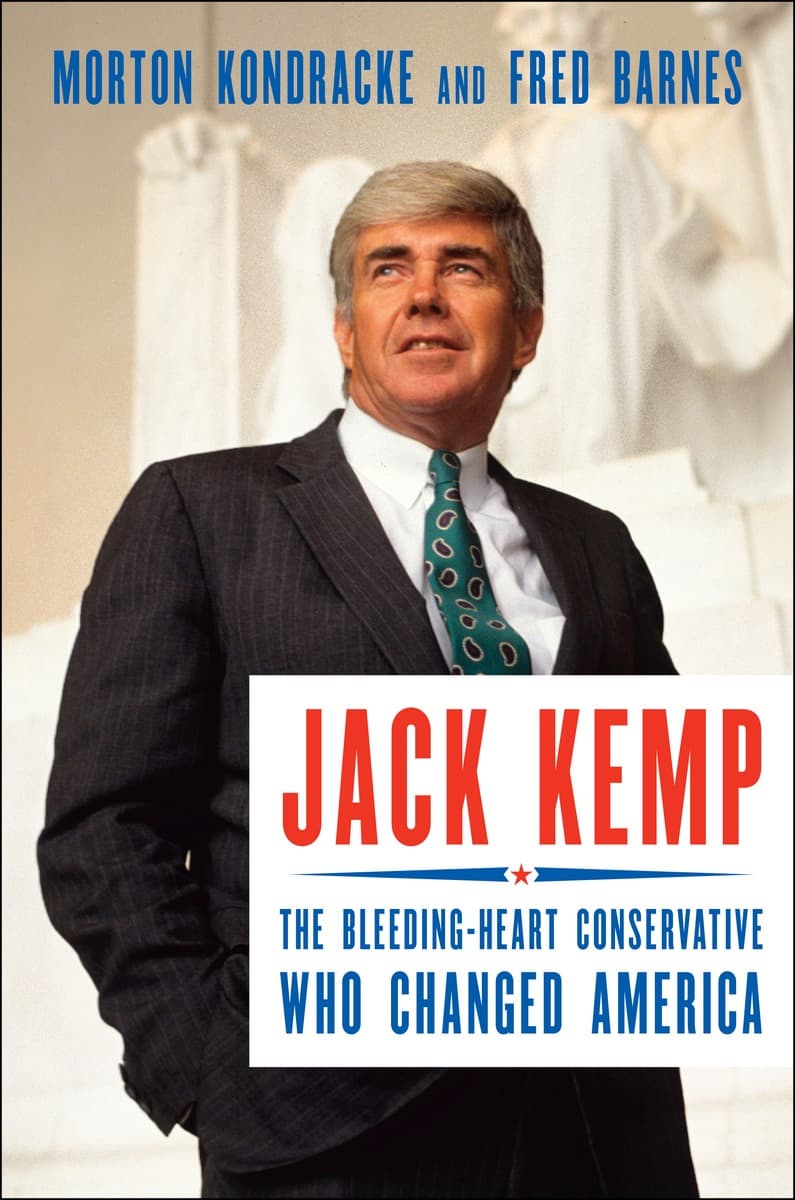

A new book, "Jack Kemp: The Bleeding-Heart Conservative Who Changed America," argues that Kemp was the most important Republican of the 20th century who was not president. The authors, Fred Barnes and Morton Kondracke, join Here & Now's Jeremy Hobson to explain why.

Book Excerpt: 'Jack Kemp'

By Fred Barnes and Morton Kondracke

Introduction

Jack Kemp was the most important politician of the twentieth century who was not president, certainly the most influential Republican.1 No one has yet written the story of his impact on America and the world. His life and legacy need to be recognized—and that’s starting to happen. In this era of political bleakness, both Republicans and Democrats are citing him as a model of what politicians ought to be. That is one of the four reasons why we have written this book.

Above all, Jack Kemp merits a prominent place in American political history because he was Congress’s foremost advocate for supply-side economics and the man who steered Ronald Reagan toward adopting it. Hence, he deserves partial credit for not only pulling America out of the deep malaise of the 1970s but also for helping to win the cold war and convert much of the world to democratic capitalism.

The ’70s were a dismal decade. It was the era of stagflation— simultaneous high unemployment and soaring inflation. And also of geopolitical reverses: it was the post-Vietnam era, when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan; its Cuban allies advanced in Africa and Central America; and revolutionary Iran held Americans hostage for 444 days. And it was an era of bottomed-out national morale—its nadir when President Carter blamed the acquisitiveness of the American people for the country’s seemingly incurable ills.

In the 1980s it all turned around. The “misery index” (unemployment plus inflation) fell from 23 in 1980 to 7.7 in 1986.2 The Soviet empire retreated, tried to reform itself, and then collapsed. Among American citizens, satisfaction with the condition of the country rose from a low of 12 percent in July 1979 to 69 percent in June of 1986.' And around the world – especially in Eastern Europe, but also in Latin America and Asia-democratic capitalism was deemed to be "the end of history."

Jack Kemp was at the center of the great turnaround. He did not invent supply-side economics: the combination of lower tax rates, particularly on individual income, and a stable dollar. That was the work of two young economists, Robert Mundell, later a Nobel Prize winner, and Arthur Laffer. But once converted by journalist-agitator Jude Wanniski, Kemp became the leading political evangelist of the supply-side movement. Lowering tax rates, he argued, would create incentives for work, savings, and investment-and produce booming growth in a way that Keynesian public spending programs had not. His tax bill Kemp-Roth, a three-year, 30 percent across-the-board cut borrowed from John F. Kennedy's 1962 proposal-became the vehicle for the supply side revolution.

Kemp's enthusiasm for supply-side economics was contagious, and he spearheaded a national movement that amounted to both a political and intellectual revolution in economics. In Congress, senior Republicans resented the presumptuous backbencher, still in his forties, who was treading on tax turf. They also doubted his economics. But junior Republicans unhappy with their party's lack of vitality joined Kemp's campaign-among them the future Speaker Newt Gingrich, the future Senate majority leader Trent Lott, future senators Connie Mack and Dan Coats, and longtime party leader Vin Weber. Kemp forged links with policy intellectuals in Washington and New York, including Irving Kris tol and Robert Mundell. Kemp's office and living room became scenes resembling graduate seminars where the Washington-New York nexus came together for debate, but with major policy change as its aim. That aim was achieved; Kemp-Roth became official party policy in 1978. Even GOP graybeards who had previously scorned him signed on.

Then he recruited Ronald Reagan, who made Kemp's proposal at the top rate from 70 percent to 50 percent, then 28 percent—set off an economic boom that lasted into the 2000s.

The achievements of the 1980s were mainly Reagan’s, but their economic underpinning was Kemp’s. No Republican politician of the twentieth century who was not president transformed the country the way he did—not Henry Cabot Lodge, Robert Taft, or Nelson Rockefeller. Earl Warren did, but as chief justice, not as governor of California. Nor did any Democrats except Hubert Humphrey, the leading early advocate for civil rights, and Edward Kennedy, author or bipartisan coauthor of dozens of health, education, and civil rights laws.

Our second reason for writing about Kemp is that he embodied a spirit sorely missing in today’s politics—in both parties. Kemp was positive, optimistic, idealistic, energetic, growth- and opportunity- oriented. He was incapable of personal attack and negative campaigning, even when it cost him. “The purpose of politics,” he said, “is not to defeat your opponent as much as it is to provide superior leadership and better ideas than the opposition.”4 He criticized liberals and Democrats, but also, “green- eyeshade,” austerity-minded, “Herbert Hoover” Republicans. His criticisms were always based on their ideas and policy proposals, never their motives or personal flaws. He believed—as he said again and again—that “ideas change history.” He wanted to change history for the better.

He wanted his own party to once again be “the party of Lincoln.” Even before very conservative audiences, he argued that the GOP should again become the “natural home of African-Americans,” as it had been from Lincoln’s time to Franklin Roosevelt’s. He insisted it could happen if Republican policies brought growth and prosperity to inner cities. It was unrealistic, probably romantic. But it was sincere. It was famously said of him that as a pro-football star, he’d “showered with more African-Americans than most Republicans had ever met.” He lamented that his party had been largely absent from the civil rights movement and regarded the “Southern strategy” to win white votes at the expense of blacks a “disgrace.”5

Kemp believed in what he called the American idea-that the Declaration of Independence was a universal document, that everyone every where deserved the right to advance as far as his or her talent and effort would lead. The American idea was Kemp's version of Lincoln's bedrock principle that the "right to rise" was the central idea of the United States and applied to black slaves as well as white workers.' And like Lincoln, he believed it was the job of government to enable people to achieve their aims and remove obstacles-especially, in Kemp's view, high taxes.

We hope this book will inspire-or embarrass-present-day politicians to see there is a better way to conduct their business. To fight, yes, but over ideas for making America better. And to search for common ground to solve America's problems and secure a future for every citizen.

Our third reason for writing this book is simply that Jack Kemp led a fascinating, inspiring life. His father, Paul, was his model of entrepreneurial capitalism. His well-educated mother, Frances, was his cultural and intellectual spur. They both were Christian Scientists, which produced in Kemp a lifelong optimism, a faith that thinking positively can change the future, that failure is never final, that "when one door closes, another opens."

Kemp grew up a sports fanatic, deciding at age five that he wanted to be a professional quarterback. By will and determination, he overcame repeated obstacles and became one, a star quarterback, first for the San Diego Chargers, then the Buffalo Bills. He remained a quarterback in mentality all his life. He was a natural leader, the captain of nearly every team he ever joined and president of the American Football League Players Association. In the turbulent 1960s, he fostered racial integration of AFL teams and cities. He never stopped applying lessons from football to life and politics-quarterbacking as capitalism, the huddle as cooperative endeavor, booing as no big deal, the next play as the chance to win.

Deeply read in economics, an expert in defense and foreign policy, and an avid consumer of history books, especially biographies of his heroes Lincoln and Winston Churchill. After Reagan won the presidency, Kemp became the number three leader of House Republicans. He was a Reagan loyalist but had the courage to oppose his president—and took heat for it—when he thought Reagan was being led astray on economic and foreign policy.

In 1988, he was deemed by many to be Reagan’s natural political heir. He ran for president urging voters to join him in “the progressive, conservative, radical, revolutionary Lincoln Emancipation wing of the Republican Party.”7 He finished a distant third behind conventional Republicans George H. W. Bush and Bob Dole. As Bush’s housing secretary, he fought a losing battle to make the plight of the urban poor a national priority. He also could not resist meddling in foreign and economic matters not in his portfolio. His fellow cabinet members were not amused.

After Bush lost to Bill Clinton in 1992, Kemp started out as the clear favorite of the party faithful for 1996. But he lost support by opposing California’s anti-immigrant Proposition 187 in 1994 and otherwise flouting conservative Republican orthodoxy. He passed on running. Then he was plucked from near obscurity by Dole, his long-standing foe, to run for vice president. But he couldn’t do what number twos are expected to do—attack the opposition. Bill Clinton’s ethics, personal and political, were a ripe target, but in debate with Vice President Al Gore, he whiffed.

The Dole-Kemp candidacy was doomed in any event because the president was popular and peace and prosperity reigned. But Kemp made a statement late in the race in Grand Rapids, Michigan, that summarized his experience and mentality:

“Wow, almost forty years ago, I started my professional career with the Detroit Lions as their third-string quarterback. And they said I would never make it. I came from the wrong schools. I was too short. I threw too hard. I was too optimistic. I didn’t have it. I tell you what. I never gave up. I got traded, sold, hurt, cut, booed, knocked out, but I never gave up. Bob Dole in his career never gave up ... Bob Dole and Jack Kemp are fighters. We believe in the American dream."

Personally, writing this book has given us the opportunity to revisit our experience as journalists. Barnes, who became a conservative in the 1970s and was a close friend of Kemp's foremost journalistic booster, columnist Bob Novak, got to know Kemp in 1981. Curious about what supply-side economics was all about, he traveled with Kemp to Buffalo for a weekend and scarcely got to ask a question. Kemp talked nonstop, determined (as always) to make a convert. Thereafter, Barnes interviewed Kemp numerous times, got close to his staff, and wrote dozens of articles about him, his favorite issues, and his political prospects, first in the Baltimore Sun, then in the New Republic. He and his family became friends of the Kemps as well. His wife, Barbara, still attends Joanne Kemp's weekly Bible study meetings, and his daughter, Karen, was a member of Kemp's youth delegate slate for the 1988 Republican National Convention, though she didn't make it to the convention because Kemp lost the state's primary.

Kondracke, once a liberal (though not very), was pitted every week against Bob Novak on TV's McLaughlin Group and was a longtime supply side skeptic who thought Reagan's admitted economic successes were the result of Keynesian deficits, not tax cuts. Kondracke knew Kemp, admired his "bleeding heart" predilections and obvious sincerity, and wrote about him intermittently for the Capitol Hill newspaper Roll Call. Then, in 2011, he was retained by the Jack Kemp Foundation to conduct more than a hundred recorded interviews for its Oral History Project. He then spent two academic years holding the Jack Kemp Chair in Political Economy at the John W. Kluge Center for Scholars at the Library of Congress researching Kemp's career. He's read Kemp's words and seen him through the eyes of fellow football players, staff

Kemp’s courage in bucking his party and even his president, his inclusiveness, and his refusal to see politics (in Newt Gingrich’s phrase) as “war without bloodshed.” Kondracke asked numerous interviewees how it was that this competitive star, playing one of America’s most violent sports, wouldn’t “hit” a political opponent. The repeated answer was: “Because he was a quarterback!”

Finally, and most important, we have written this book because we believe that America is in trouble, perhaps more deeply in trouble than in the 1970s. And we think that Jack Kemp’s spirit— and his policy ideas—could again help the country turn around.

The American Dream is dimming. Workers have the right to rise, but they are not rising. The median income of American households in 2013 was 8.7 percent below what it was in 1999 after climbing by 20 percent during the ’80s and ’90s.10 At the same time, workers’ contributions toward health-care premiums have risen almost four times faster than their wages.11 People born in the lowest fifth in income distribution have just a 9 percent chance of reaching the top fifth, showing no improvement over the past thirty years. And there has been no progress in fifty years in closing the wealth gap between whites and minorities.12 As the economy recovers from the Great Recession, 95 percent of the nation’s income gains have been reaped by the top 1 percent of earners.13 Meantime, while the official unemployment rate has dropped, the underemployment rate has recovered much less.14 And millions have dropped out of the labor force.

The slowing of economic opportunity has deleterious psychological, social, and political effects. In 1992, 41 percent of Americans were confident that their children’s lives would be better than theirs; in mid-2014, only 21 percent were optimistic. A CNN/ORC (Opinion Research Corporation) poll showed 59 percent believed “the American dream has become impossible for most people to achieve.”15 Whether it’s a cause or an effect, America’s social capital is also flagging. The out-of-wedlock birthrate, heavily correlated with a life of poverty, has doubled since 1980.16

In a speech to the 1979 International Longshoremen's Association convention, Kemp said that "in a stagnant or contracting economy, politics becomes the art of pitting class against class, rich against poor, white against black, capital against labor, Sunbelt against Snowbelt, old against young."17 The increasingly savage polarization of American politics today is at least partly the result of citizens' fear and anger that "others"-"the 1Percent" or "the 47 percent"-are profiteering at their expense.

This polarization makes it impossible for Democrats and Republicans to solve other deep problems: an immigration system that every one agrees is "broken"; an education system that costs double per pupil what it did in 1981" yet produces high school graduates only a quarter of whom are ready for college;19 infrastructure ranking nineteenth in the world;20 a health-care system that costs more per capita than any country in the world except Switzerland's/1 and a gross federal debt already 103 percent of GOP, nearly as high as at the end of World War II,22 and destined to climb as the baby boom generation ages."

We do not doubt that poor leadership is heavily to blame for the country's condition. Good leadership turned a bad situation to good in the 1980s. But it's not obvious who can provide it today. We hope today's would-be leaders will try to follow Kemp's example.

Conditions are different from those in the Kemp era. Kemp could be careless about the size of the national debt and he opposed nearly every effort to reform entitlements or reduce benefits. For much of his career, he thought the supply-side formula-reducing marginal tax rates and returning the dollar to the gold standard-would guarantee growth, prosperity, and hope. Until he was HUD secretary, he believed in john Kennedy's dictum, "A rising tide lifts all boats." Then he became convinced that "some boats are stuck on the bottom" and can't rise without government help.

We suspect we know some of what Kemp would favor now-for certain, "family friendly" tax reform; lowering rates for individuals, capital gains, and corporations; eliminating special interest loopholes but earned income tax credit for the working poor. At times he called for making workers’ payroll taxes deductible from their income taxes. He was and would be for education vouchers to give families maximum choice in selecting their children’s schools. He did and would favor comprehensive immigration reform that offered a path to citizenship to illegal immigrants with clean records. He always backed expanded free trade. He would continue advocating a new gold standard.24 He would have persisted in favoring enterprise zones and vouchers to enable the poor to find housing in the private market. He would certainly urge his party to promote growth, not austerity, and be concerned with the advancement of all Americans, not just the GOP base. He was a “big tent” Republican, ever urging expansion of the party’s appeal.

He would surely oppose the big government, Keynesian drift of the increasingly liberal Democratic Party, which deems high-tax, rich- benefit, and highly regulated European social democracies as model societies in spite of their chronically high unemployment rates.25 Kemp said that the goal of Lincoln’s Republican Party was not “the construction of a safety net under which people should not be allowed to fall, but . . . of a ladder upon which people can climb.” He said, “Yes, we need a safety net, but it should be a trampoline, not a trap. And, right now, it’s a trap.” The measure of compassion of the party of Lincoln, he said, “should not be how many people need help, but how many people do not need to be on government assistance because they’re now on that ladder of upward mobility that Lincoln called the desire to improve one’s lot in life.”26

Kemp opposed the impulse of liberals to redistribute wealth rather than create it and to disparage those who get rich rather than see them as entrepreneurs and job creators. But he was equally dismayed at the tendency of some in his own party to exclude blacks, Hispanics, union members, the poor—and the tendency to award subsidies and tax breaks to wealthy interests while imposing austerity on the less favored. When Reagan’s deficit-obsessed budget director, David Stockman, sought to raise taxes on beer and gasoline, Kemp demanded, “Dave, if we truly face a ‘budgetary Dunkirk,’ why are food stamps, AFDC, Medicaid and Head Start touchable, but not Exxon, Boeing and Gulf Oil?"zl Had he been alive, he would have asked the same in 2014 when House Republicans attempted to reduce food stamp spending but maintained crop subsidies for rich farmers.

Kemp had his flaws. He was undisciplined and impatient. He could not force himself-or be forced by aides-to make a short speech, and it hurt him politically. He mystified audiences with references to obscure historical figures and lost them with lectures on the gold standard. He over promised when asked to help GOP candidates, driving his schedulers crazy. He was chronically late and sometimes reckless behind the wheel trying to make it to events or airports. He barked at aides and blamed them when something went wrong, then made up (usually without apologizing). He played one staff member off against another-evidently to maintain control. His loyal congressional staff worked around it.

He was mistaken on some key issues, especially foreign policy. Reagan, much wiser than nearly every international affairs "expert," understood that the Soviet Union was fundamentally weak and could be defeated if pushed hard enough. He also wanted to bargain with adversaries, though only from strength. Reagan proved more of an optimist than Kemp, and also more of a pragmatist. And he won the cold war.

But Kemp's virtues far outweighed his faults. He was passionate about ideas-relentless, in fact, to the point that members of Congress sometimes hid to avoid his lectures and importuning. He held no grudges and had no enemies, thinking there was no one he couldn't convince if he worked on them long enough. On the football field, he looked at opponents-"the people who tried to knock my head off on Sunday"-as friends. His political adversaries were "opponents, not enemies." A close friend, ex-education secretary and drug czar Bill Bennett, once told him, "jack, if you believed in original sin, you'd be president." Kemp did not believe anyone was a hopeless sinner.

Above all—and this is the main reason we have written this book— he was positive, optimistic, and in the best sense of the words he used to describe himself, “progressive,” “populist,” “radical,” “conservative,” and “liberal minded.” He thought large: about changing the whole basis of U.S. economic policy, fiscal and monetary; about government as “the Good Shepherd” leaving no lamb to be lost; about spreading freedom and prosperity around the world. His was a spirit that barely survives in the mean politics of the present day. We hope this book will help change that.

Excerpted from Jack Kemp: The Bleeding-Heart Conservative Who Changed America by Morton Kondracke and Fred Barnes with permission of Sentinel, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © Frederic Wood Barnes, Jr. and Morton M. Kondracke, 2015.

Guests

- Fred Barnes, political commentator and executive editor of The Weekly Standard. He is co-author of "Jack Kemp." He tweets @FredBarnes.

- Morton Kondracke, political commentator and journalist. He is co-author of "Jack Kemp."

This segment aired on September 29, 2015.