Advertisement

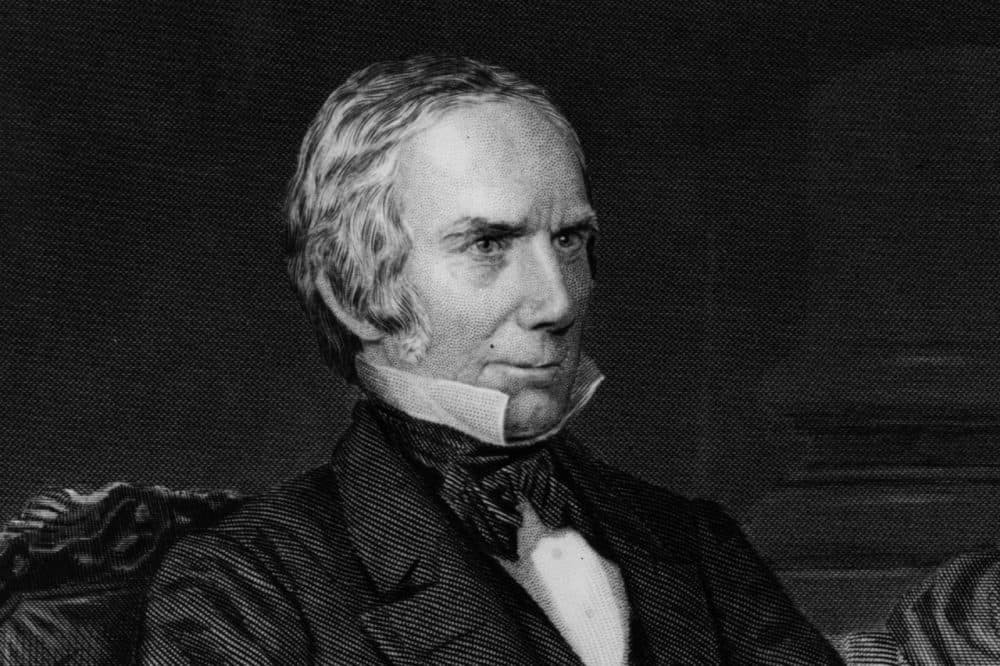

Lessons From Speaker Henry Clay, 'The Great Compromiser'

A new book argues that Henry Clay, a Kentucky lawmaker, was America's greatest statesman. Clay served under 10 presidents during his long legislative career, which included many years as speaker of the House.

Throughout his time in Washington, he worked with bitter political foes to reach compromise on difficult issues like slavery. Historian Harlow Giles Unger says Clay helped to preserve the union in the half-century before the Civil War.

Unger discusses Henry Clay and his new book, "Henry Clay: America's Greatest Statesmen," with Here & Now's Jeremy Hobson.

- Harlow Giles Unger: Congress Needs a Speaker Who Can Compromise

Book Excerpt: 'Henry Clay'

By Harlow Giles Unger

In January 1816 Speaker Clay startled Congress by proposing the reopening of the Bank of the United States, whose closure he himself had engineered only five years earlier before the start of the War of 1812. Chartered in 1791 at the behest of then secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton, Congress had created the Bank of the United States as the federal government’s own bank to deposit and withdraw funds for day-to-day government operations. The bank also printed currency and sold bonds to the public when the government needed extra cash.

By 1811, when Congress needed to renew the bank’s charter, English bankers rather than Americans had snapped up two-thirds of the bank’s outstanding bonds and stock—just as sentiment for war against Britain had reached explosive proportions. Adding to resentment of British control over the national bank was the growth in the number of state and local banks—more than one hundred—each printing its own currency. Few had enough specie—if any—to back their currency and compete with the Bank of the United States.

Advertisement

Henry Clay had used every power of his House speakership to defeat rechartering the national bank, even leaving the Speaker’s chair to argue—as Jefferson had in 1791—that the national bank was unconstitutional and that the Constitution did not give the federal government power to establish its own bank or any other private corporations. Brilliant orator that he was, Clay triumphed.

Five years later he reneged. For anyone but Clay it would have been a public humiliation. By then, however, eighteen state banks had flooded markets across the nation with various currencies—all of them worthless on international markets—and without a bank of its own to issue a national currency, the Treasury defaulted. Rather than risk ridicule and hear his own earlier arguments against a national bank hurled at him, Clay remained aloof during the House debate and let one of his original war-hawk allies, South Carolina’s John C. Calhoun, lead the struggle to reestablish the national bank. Unlike Clay, the stern-faced Calhoun had favored rechartering the First Bank of the United States in 1811, and he now won the day in establishing the Second Bank of the United States.

Like Clay, Calhoun was born a country boy, growing up on a prosperous 2,000-acre farm in western South Carolina, one hundred miles from the nearest settlement. Thirty slaves tilled the corn and wheat fields and tended the cattle, hogs, and sheep. Calhoun’s father died when the boy was still in his teens, but at six-feet-two inches and with the strength of someone twice that height, John joined his brothers in running the farm. Eighteen years old in 1780, he came under the influence of a brilliant itinerant teacher and, with financial support from his older brothers, traveled north to New Haven, Connecticut, to enroll at Yale College. After earning his degree he went to Litchfield, Connecticut, to study law at Tapping Reeve’s law school—the first such school in America. Unlike Clay, Calhoun was blunt and direct in his speech, whether to an individual, a jury, or his colleagues in the House. An intimidating figure with an intimidating face, he never relied on histrionics and rarely smiled. He was a perfect political ally for the theatrical Clay, whose wide mouth seemed locked in a perpetual grin.

Clay tried staying aloof during the debate, but so few House members understood the financial complexities of a national bank that they demanded an explanation for Clay’s change of heart. With his usual bravado, Clay insisted that, as a senator in 1811, he had had no choice but to follow the Kentucky legislature’s instructions to vote against rechartering the bank to protect the state-chartered Bank of Kentucky against competition by the national bank. Furthermore, as Thomas Jefferson had claimed when Congress chartered the first national bank in 1791, the Constitution had not authorized the federal government to create a corporation nor did it authorize Congress to continue the bank in 1811. But in one of the most important declarations in congressional history, Clay now insisted that the Constitution gave Congress “implied powers” unmentioned in the actual language of that document. Alexander Hamilton had presented the same argument nearly forty years earlier.

Hamilton had cited Section 8 of the Constitution giving Congress power “to make all laws . . . necessary and proper for carrying into execution” its constitutional powers. “A bank is . . . an essential instrument in the obtaining of loans to government,” Hamilton insisted.

Clay now expanded Hamilton’s argument:

The Constitution vests in Congress all powers “necessary and proper” . . . to put into motion and activity the machinery of government which it constructs. The powers that may be so necessary are deductible by construction. They are not defined in the Constitution. They are from their nature indefinable. When the question is in relation to one of these powers, the point of enquiry should be, is its exertion necessary to carry into effect any of the enumerated powers and objects of the general government?

In effect, Clay broadened Hamilton’s interpretation of the Constitution, declaring Congress ruler of the nation, with the “necessary and proper” clause giving the legislature all but supreme power.

Clay’s dictum officially embraced constitutional activism. Like Hamilton, he insisted that “a total change in circumstances” and “events of the utmost magnitude” had changed the obligations and powers of government.

Under Speaker Clay, Congress authorized capitalization of the Second Bank of the United States with $35 million, to be raised with the sale of stock. The bank would then buy outstanding government paper (bonds), thus driving its market value higher and, gradually, restoring the value of US currency. Although offered the presidency of the bank, Clay refused, believing that his colleagues and, indeed, his supporters in Kentucky might question his motives for supporting recharter. He nonetheless purchased five shares in the bank and told its president, William Jones, that “I will cheerfully render any service in my power to an institution whose prosperity I consider indissolubly connected with that of the country.”

Clay’s embrace of extended federal government powers into banking did not sit well with voters in Kentucky and other western and southern states. Clay added to their displeasure by supporting a bill to raise congressmen’s salaries from $6 a day (about $900 a year) to a new flat rate of $1,500 a year, regardless of hours spent on the floor of the House. The Speaker’s salary, already $12 a day (about $1,800 a year), would climb to $3,000 a year. Far from being the “salary grab” that many critics called it, the shift from daily to annual pay was a response to criticisms that, as life in Washington had improved, Congress was unnecessarily stretching the days it remained in session to collect as many pay days as possible.

When he returned home to campaign for reelection in the summer of 1816, Clay found many once-adoring supporters infuriated by the pay increase. His opponent was Federalist John Pope, who had lost an arm as a youth. Pope charged Clay with having voted for the “salary grab” to pay for the luxurious way of life he had acquired while in Europe and imported to Kentucky to enjoy in his lavish mansion at Ashland.

Many voters agreed. One longtime friend and loyal political supporter shocked Clay by declaring, “Mr. Clay, I have concluded to vote for the man who has but one arm to thrust into the treasury.”

Clay’s European stay and his intimate contact with the high-born—British prime minister Lord Castlereigh, Lord Gambier, Madame de Staël, the Duke of Wellington, and the like—had indeed changed his outward personality. No longer the clumsy country boy who stumbled into Richard Denny’s Richmond department store, he had traveled through western Europe invariably addressed as “Your Excellency.” He had dined with Europe’s nobility and its most celebrated figures in the arts, sciences, and government. By now he had embellished the interior of his Ashland home to rival chateaux of European nobility. It included arched doorways, an octagonal entry hall, an octagonal library with ash and walnut paneling, and a domed skylight to augment the light.

“His disgusting vanity and inordinate ambition,” Virginia senator Armistad Thomson Mason grumbled, “were fast destroying his influence and his usefulness as a public man.”

The changes in Clay were evident to neighbors, friends, and voters—even his family. Unable to cope with the unruly behaviors of his two oldest sons, fourteen-year-old Theodore and thirteen-year-old Thomas, he sent them away to a boarding school so he could focus on his campaign.

His wealth and new tastes had not dulled his wit, however. After a former supporter voiced his displeasure and said he would vote for Pope, Clay retorted, “Have you a good rifle, friend?”

“Yep.”

“Did it ever flash?”

“It did, once.”

“And did you throw it away?” asked Clay.

“No. I picked the flint, tried it again, and it was true.”

“And will you throw me away?”

Flustered by Clay’s question, the voter thought for a few seconds, then agreed he would not vote against Clay.

Excerpted from the book HENRY CLAY: AMERICA'S GREATEST STATESMAN by Harlow Giles Unger. Copyright © 2015 by Harlow Giles Unger. Reprinted with permission of Da Capo Press.

Guest

- Harlow Giles Unger, historian and author of "Henry Clay: America's Greatest Statesmen."

This segment aired on October 9, 2015.