Advertisement

This Benedictine Monk Travels The World Helping Preserve Centuries-Old Manuscripts, Cultural Heritage

Resume

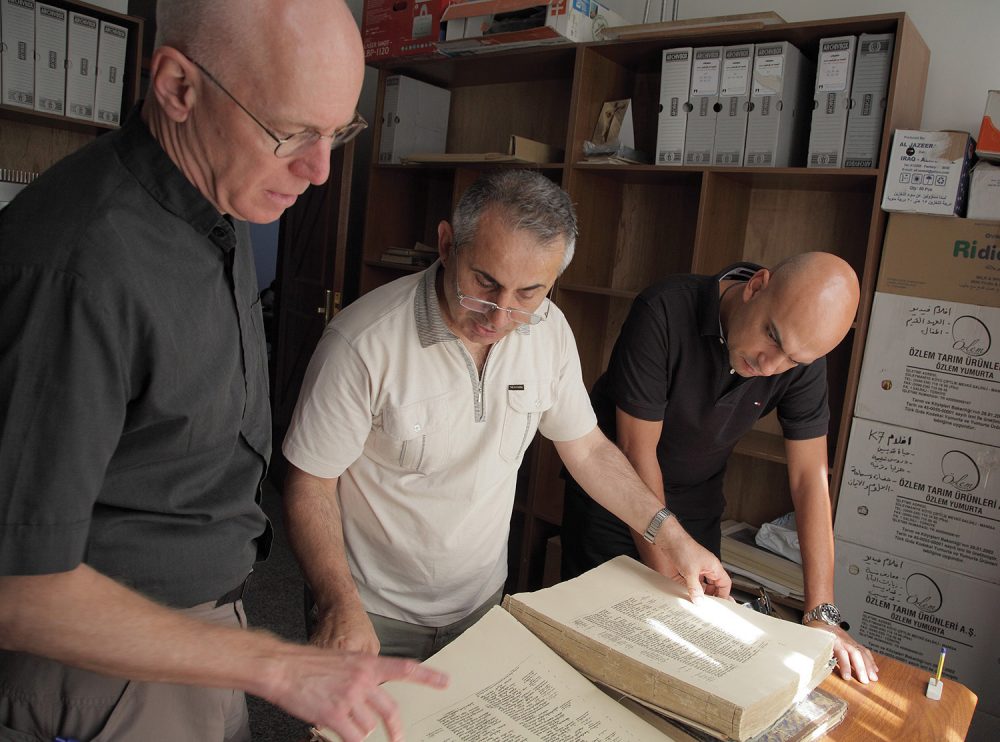

Father Columba Stewart (@ColumbaStewart) has spent more than a decade traveling to some of the world’s most dangerous regions — Iraq, Syria, the Balkans — to find and preserve manuscripts, many of them centuries old. And now, with the rise of ISIS, his work has become more urgent than ever.

The 59-year-old Benedictine monk has so far helped locals photograph an estimated 140,000 manuscripts, over 50 million handwritten pages. He’s director of the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library (@visitHMML) at Saint John’s Abbey and University in Collegeville, Minnesota, and joins Here & Now's Robin Young to discuss his work.

Links To Manuscripts

Interview Highlights

On the kinds of manuscripts Father Stewart and his colleagues work with

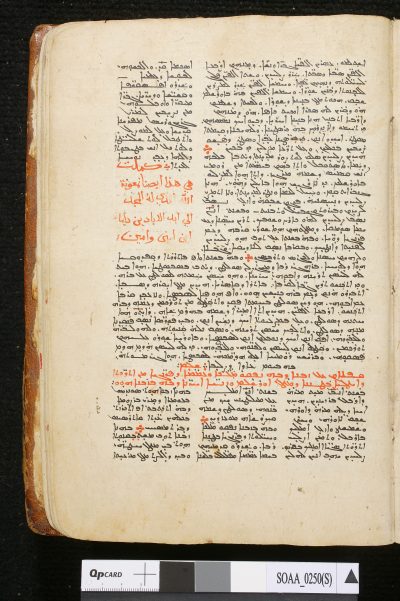

"We've worked with manuscripts as various as palm leaf archival material in India, to beautiful illuminated manuscripts that we found in Iraq. Beautiful illustrations, which tell you something about the culture, not only in terms of how they interpret a story, say, from the Bible, but also how they view the world and how they depict reality in their art. So a lot of the manuscripts are pretty unremarkable. There are simply a way of preserving a text. So the average person may look at it and say, 'Well, I expected a book of hours or something with lots of gold.' But to the scholar, of course, these things can be gold because it might be the only copy of a text that's otherwise lost, or a translation of a text from another language, which tells you something about how ideas and writings flow from one culture to another. So you really never know what you're going to find until somebody takes the time to read it."

On some of his most exciting finds

"So here's an example. There's a history of the world that was preserved in a 15th century manuscript. The text actually dates from the 12th century, but the only copy we have of it in the original Syriac language was the 15th century manuscript. And that manuscript was in southeast Turkey, and it was taken from Turkey to Syria in 1923 when the Christian population of a certain city had to leave, and they went to Aleppo for safety. That manuscript tells the story of Christians in the Middle East and what happened to them when the Crusaders arrived from Europe to liberate the Holy Land and to claim it back for Christians. And of course it was the local Christians who took the heat in response. So we read that kind of story, and it makes us look at some of the current events perhaps with different eyes."

On increasing threats to these manuscripts due to regional conflict

"We feel that pressure all the time. We started the current round of our work around the time that I became the director in 2003 working in Lebanon. So we've seen the dissolution of the Middle East as it has been known now for decades, just in the time that we've been working. And the work we're currently doing in Mali in West Africa with the manuscript of Timbuktu is another place which experienced a very sudden dislocation with the appearance of a kind of Islamist and nationalist uprising in the north of Mali and the evacuation of manuscripts. None of these things could have been foreseen. So in a way it was really extraordinarily providential that we were working where we were or that there were people on the ground who belonged to these cultures who had the foresight to move things before it was too late."

On training locals to do the photographic preservation

"A lot of these communities have long memories, and they remember what happened in the 16th, 17th, 18th, 19th centuries when Europeans came and took their manuscripts. And that's what makes the great manuscript libraries of Europe now. So they are often rightfully suspicious toward the foreigner who shows up with an interest in their manuscript heritage. So we're trying to do it a different way. We're trying to bring our expertise to these local communities so that they have the privilege — and also a paying job — of working to preserve their own cultural heritage."

"The average person may look at it and say, 'Well, I expected a book of hours or something with lots of gold.' But to the scholar, of course, these things can be gold because it might be the only copy of a text that's otherwise lost."

Father Columba Stewart

On losing the original copies of the manuscripts

"So I suppose the the analogy, not to overdramatize, would be looking at a photograph of a loved one who's no longer with us. The picture is precious — it's a reminder — but it obviously is only a stand in for the person, and the same is true even of high quality digital images. They're great for scholars to work with, but a manuscript not only has a kind of almost sacred power when you hold it, but there are also things about the physical object that it will only tell you if you hold it in your hand. You get a better sense of how it's actually put together. You have a closer encounter with the binding structure. You can examine more closely the fabrics or papers or old leaves of manuscripts that they've used to hold the manuscript together. And then there's also the value of seeing a manuscript as part of a collection or a library."

On where these manuscripts are often found

"You'll find them in churches. In some cases they are family libraries, which have been kept often for centuries because there was a scholar at some point in the history of the family, and they've kept them as is true of some of the Muslim families we've worked with in Jerusalem. Sometimes they're hidden deliberately behind a false bookcase and then there's a secret door and beyond that there's a marvelous room full of manuscripts so we've really seen just about every possible form of storage."

On convincing people to let him to view their collections for preserveration

"Well, you don't make a cold call. First of all we try to learn where there might be important manuscript collections that need to be preserved either because they might be in danger or because they're so important that scholars really want to see them. So then we try to figure out who could be introducer or an influencer, a member of that community, maybe a scholar who is trusted by them, and that's the bridge. And then I'll go and meet them and try to establish my own personal relationship with them."

"In every instance it's a matter of their being convinced that we respect them even if we don't understand or know everything about their culture, and that we are not in it for any kind of personal profit."

This segment aired on March 13, 2017.