Advertisement

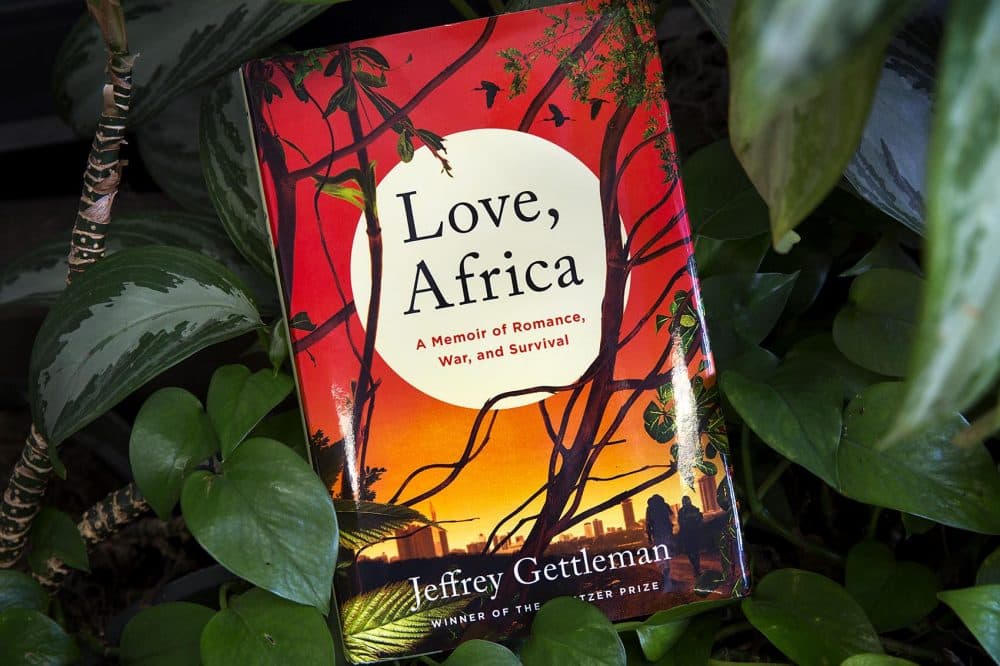

New York Times Correspondent's Memoir A Love Letter To Africa And Journalism

After a visit to East Africa in college, Jeffrey Gettleman (@gettleman) set his heart on finding a way to return and make his life there. "Love, Africa" is the story of how he made his way back — and the conflicts he covered along the way.

Gettleman won a Pulitzer Prize in 2012 for his reporting from East Africa. He speaks with Here & Now's Robin Young.

Editor's Note: The excerpt below contains some explicit language.

More Photos

Book Excerpt: 'Love, Africa'

By Jeffrey Gettleman

ITHACA, 1990

Every day, after my 3:35 class ended, I hurried back to the frat house to check my mailbox. Many of the letters started the same: “My beloved friend . . .”

Some asked for a camera, others for clothes. Most asked for nothing, just sharing the news from rural Tanzania or backroads Malawi, the two agrarian countries where I had been five months earlier. One boy, Macfereson Banda, from Karonga, Malawi, wrote to see how our soccer ball was doing. “When I played with it,” he said, “I was really feeling as if I am on top of the mountain.” I won’t lie. We had met thousands of kids driving from Nairobi to southern Malawi on a homemade mission to bring aid to refugees. I didn’t remember who Macfereson Banda was. But I remembered that spirit, that drive to get close and stay close.

The letters from East Africa came in slender, tissue-thin envelopes trimmed in red and blue. The envelope was the letter, so I was careful slipping the blade of a knife under the seam. As I sat at a long wooden table in our dining room, happily rereading the week’s Africa mail, Michael Laudermilk sauntered in, wearing a Lakers tank top and thumping a basketball.

Advertisement

“Gettlemern”—mern was our word for nerd—“what you doing?”

Laudermilk—Milk—was my same year. He stooped above me. The ball stopped bouncing.

“Those airmail?”

“Yup.”

He bent closer, glancing at the stamps.

“Africa, huh? You were there over the summer, right? What’s Africa fucking like?”

I looked up at him. His handsome face was framed by glossy black hair. Milk was a star safety on the varsity football team, built like a gladiator, unjustly athletic. We weren’t close, and for the first time he seemed genuinely interested in something I had to say.

“It’s like . . .” My mind started to race. “Like . . .” I looked out the window, off into the naked Ithaca trees. I hated that question.

How much did Milk really want to know? What was I supposed to say? That question still trips me up, and back then I definitely didn’t have the poise to hop over it. My first Africa trip had been like a lucid dream—and I was possessive of this dream, because dreams lose their power if you start sharing them around. It began the moment I’d landed and stood eagerly in the aisle, peering out the windows, waiting for the stewardess to wrench open the door. When that dry canned airplane air rushed out and Nairobi’s fresh cool night air rushed in, rich and loamy, like a million wet leaves, it was an immediate intoxication. That’s how that whole summer went, our truck chugging down the road, one thing morphing into the next, things just seeming to happen, leaving behind this sweet, heavy, mysterious emotional aftertaste.

It felt like every day we discovered something; of course that was an illusion, but the illusion was rarely broken. Our summer was a road trip, we covered a thousand miles over four weeks across eastern and southern Africa, we did see a lot. The afternoon we rolled into Salima Bay, on Lake Malawi, was no more or less eventful than dozens of other long sunny lazy days we shared, but it remains deeply etched. Lake Malawi was an inland sea; you couldn’t see across it. The water was coppery, the sand by the shore burning.

We stripped off our shirts and ran in, pushing the water away with our thighs. It seemed to get thicker each step. Immediately we were surrounded by dozens of kids thrashing toward us, belting out “Mzungu! Mzungu! Mzungu!”—the equivalent of gringo. We couldn’t communicate, but that didn’t stop us from playing with the slippery little kids and throwing them into the water and wrestling on the beach with the bigger ones. They cheered at just about everything we did, and after I toweled off and dressed—in front of a crowd of about ninety-five—scraps of paper were thrust into my hands. Where from! What district! What village! The children wanted to be pen pals, and I scribbled out my address as fast as I could. They tugged us toward their huts, and I peered into one, a little round house, roof black from smoke. There was nothing inside, no toys, no balls, no books, no mattresses even, just blankets bunched up on a clean dirt floor. Malawi was one of the poorest countries on earth; I had never seen anything like this. I felt something on my leg. I looked down. A little boy, about four, was rubbing my shin. People here don’t have hairy legs. His warm little fingers tickled like a spider. As I was standing in the doorway of his house, checking things out, he continued to move his fingers up and down the ridge of my shin extremely lightly, feeling my hairs. It was one of the most intense moments of mutual curiosity I’ve ever experienced.

This was a different world. Personal space didn’t exist. Grown men walked down the beach holding hands, and once when I was standing in the middle of a pack of fishermen, I felt a set of rough calloused fingers interlace in mine. I liked that. I squeezed back. It made me think that maybe out here, you didn’t have to move through life hopelessly alone.

Our guide to this new world was just a year older. His name was Dan Eldon and I’d never met anyone like Dan Eldon. He’d blaze into a restaurant, snap a stiff salute to the waiters, flick them a cassette, and the next thing I’d know, there would be one white face in the middle of a circle of waiters, everyone grooving together and singing out loud in one voice with several different accents: “Fight the power! We got to fight the powers that be!”

The first time I saw Dan was in Mombasa, swimming in an ocean that was a shade of bright blue that didn’t look like any water I’d ever seen before; it was the color of Windex. Dan was paddling just beyond the waves. When someone pointed him out, I was surprised by how young and delicate he looked, after all I had heard. He was clean-cut, with a long face, dark eyebrows, and a square jaw, but still, there was something fragile about him. We had met through a fluke. I have a childhood friend named Roko, who was friends with this guy Chris, who came on the trip to film it and knew a guy named Lengai, who had grown up in Nairobi with Dan. Dan had organized a mission to help Mozambican refugees, and he invited a dozen students to drive from Nairobi to the border of Malawi and Mozambique, where he planned to donate a car and several thousand dollars to the refugee camps.

Before we left for Africa, I held that same vague patchwork of images in my head that many people hold, of suffering, disease, deprivation, and poverty. That part of Africa is real—but it’s only that, part of the picture. Even though we were constantly aware that we had so much more than the people around us—our Nikes, our flashlights, our Walkmans, money—even though we were surrounded by people who were clearly struggling, I rarely sensed any resentment, any bitterness. Curiosity, yes; we were oddities. When we walked through the towns, things would suddenly stop; people around us would turn and stare, shoe-shiners would be suspended in mid-stroke, and I’d hear them whisper to each other, “Something-something-mzungu.” It felt like we were being worshiped, which felt wonderful—and disconcerting. It didn’t seem right to be regarded as representatives of some alien civilization that had just descended for a quick visit.

I soon learned that the playing, the wrestling, the endless grip-shifting handshaking, helped lower those barriers. My guard began to drop, inch by inch. I realized there was so much less to fear than I had originally thought. When we camped in the middle of the savanna in Mikumi National Park, animals all around us, big ones, so close we could smell their pungent musk, somehow it didn’t feel reckless. It felt as if they had their space, we had ours.

“You guys ever wonder what to do with a landscape like this?” Dan asked after we all sat down by a campfire. “It’s, like, beautiful food you can eat; a beautiful woman you can kiss; but what are you going to do with a landscape this beautiful?” Eager for Dan’s approval, we gazed out at the acacia trees silhouetted by the moon and the chest-high elephant grass rolling away for miles, wondering if there was any possible way to answer a question so profound.

Excerpted from the book LOVE, AFRICA by Jeffrey Gettleman. Copyright © 2017 by Jeffrey Gettleman. Republished with permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

This segment aired on May 22, 2017.