Advertisement

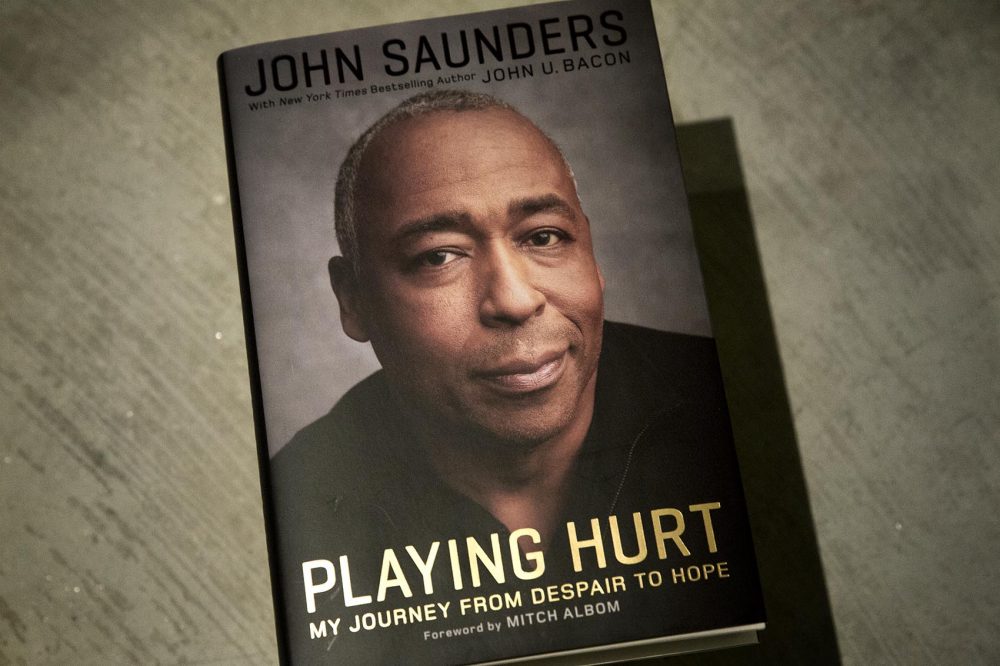

In Posthumous Memoir 'Playing Hurt,' Sportscaster John Saunders Faces His Demons

Resume

For nearly 30 years John Saunders was a steady, calm presence on ESPN and ABC Sports broadcasts. What the public didn't know was his difficult life away from the camera.

Saunders struggled with severe depression, linked in part to an abusive father. Eventually he decided to tell his story, but he did not live to see the publication of his book about the experience. Saunders died of natural causes on Aug. 10, 2016.

Here & Now's Robin Young talks with his widow, Wanda Saunders, and "Playing Hurt" co-author John U. Bacon (@johnubacon).

- More information on depression from the National Institute of Mental Health

- More information on the National Network of Depression Centers

- Find more great reads on the Here & Now bookshelf

- Scroll down to read an excerpt from "Playing Hurt"

Interview Highlights

On the life of John Saunders

John U. Bacon: "He was a great athlete, he played hockey at the University of Michigan and Western Michigan, and Ryerson University in Toronto. He played minor league hockey in New Brunswick. His brother Bernie made it to the NHL. He started his career in broadcasting on a lark, as 'Country John Saunders' in a tiny little radio station in Ajax, Ontario, and decided that he liked it, and he was actually very good at that. Within a few years, he's in Baltimore, and in '86, ESPN picks him up, along with Wanda, of course, they got married shortly thereafter. And John, for 30 years, was considered one of the top four or five sportscasters in the nation, and covered every event you could name — Super Bowl, Olympics, you name it. So his career was beyond reproach, and the respect he had in the business is really quite uncommon, because he was opinionated, he was not afraid to express himself, especially on race, and yet I cannot find anyone, to this day, who did not like John Saunders."

On the ways in which John would cope with his abusive father, including self-harm

Wanda Saunders: "There were not a lot of things in the book that I didn't know about, but there were a few, and that is one of them. He always blamed himself, 'There has to be a reason why, so it must be me,' and he carried that with him quite a while."

On John’s early brain injuries

JUB: "The catch with concussions, or what doctors called brain injuries, is that if you think you've had 10, you've probably had 20. And then of course, finally, on Sept. 10, 2011, he blacks out and falls backwards, and John's a big guy. That was a very major brain injury which put him in Mount Sinai for six weeks, to relearn to walk and talk, and read and write."

On the family life John experienced growing up

WS: "All three kids did have to struggle with both parents. It's difficult when you don't have that one person to go to. It's hard.

On John as a father

WS: "When we first met each other, I just knew, well, we're not going to have kids, he doesn't want to have kids, he doesn't think he's been a good father. But then, we did, and I would say that my girls are the luckiest girls in the world."

On John's depression

WS: "It feels like being sad when you don't have anything to be sad about, and not being able to stop it. Everything was the 10th degree as opposed to one or two."

JUB: "Almost everything turns negative. The worst possible interpretation of everything that happens to you. He also said, too, that when you get good news, praise and whatnot, your metabolism runs a lot higher and you burn through that very quickly. You need a lot more reinforcement than somebody else does, and I think that's a legacy of the child abuse, frankly.

"One phrase we came up with is, 'The world goes to black and white.' You still have a loving wife, you still have wonderful daughters, and I can't say enough about what Wanda and Aleah and Jenna did for John. They kept him going, no question. But, they can't always reach you when you're that down, so you need to get professional help, and John did. John was, you know, winning this battle, bit by bit."

"I hope that it helps somebody. I hope it helps somebody understand what they're going through, or make it a little easier for them."

Wanda Saunders

On the combination of depression and traumatic brain injuries

JUB: "The guy who made the diagnosis, if you will, that it was more than just a concussion that John was dealing with, and all that, it was Reggie Jackson, who happens to be Wanda's uncle, and staying at their house. He just went to Wanda and said, 'Something is not right with John, beyond the brain injury.' And it was Reggie Jackson who confronted John in a car, and, as John said, 'There's no BS-ing Mr. October.' So through Reggie Jackson's connections at Columbia, John got a new set of doctors, and these proved to be, I think, his best."

On John's time spent in a psychiatric hospital

WS: "I'm a very open person, so whatever he was feeling, I listened, and, if I could help, I would help. But, I think it's more important that he was able to just tell me whatever he was feeling while he was going through this process of being in the hospital. So, I think it's just the two of us just being able to talk to each other and me not thinking I can solve everything for him or help him through it. It's something that he had to go through himself."

On hopes for the book's legacy

WS: "I hope that it helps somebody. I hope it helps somebody understand what they're going through, or make it a little easier for them. I hope that people realize that you can't just suck it up and be happy, that you do need to get help. And I hope everybody really understands what a good person he was and how much he cared about other people, and wanted to help them."

JUB: "There are 30 million people in America with clinical depression, so we wanted to help those folks, as well as folks that love them."

On the decision to leave the darker moments in John's life in the book and not exercise editorial discretion

WS: "Because I knew how important this was to him, and I know how hard he worked on it, and it gave him a sense of accomplishment. And that, he will hopefully help somebody, and that I couldn't take that away from him. I know he can't say anything to me if I hadn't, but I know that it was very, very important to him. I just wanted to do it for him."

Book Excerpt: 'Playing Hurt'

By John Saunders, with John U. Bacon

My father’s death didn’t affect me the way I thought it might. I didn’t feel relief or sadness or even happiness. I felt nothing. Not numbness, but simply nothing at all. But in hindsight I might have been fooling myself, ignoring the pain his death really caused me. Our last chance to make things right had passed, forever, which might have affected me far more than I let on to anyone, including myself.

I continued to blame myself for our dysfunctional relationship—and the one man who might have convinced me otherwise was now gone. As my depression deepened, my long-dormant impulse to cut or burn myself resurfaced. Freud used to say depression was anger turned inward against yourself, and my response to my dad’s death might have been proof.

I also had suicidal thoughts pop up again while I was driving. I could hit a tree or a lamp, I thought, or drown myself in a roadside lake, and that would be it. What made things progressively worse was that I wasn’t doing anything to address these issues: no therapy, no medication, no acknowledgment that I was doing anything but gliding along, leading a perfect life.

By December of 2009, a few weeks before Christmas, my façade finally cracked under its own weight. I went to see our family doctor, Dr. Michael Gerdis, for a checkup. He’d known me for almost two decades, so as soon as he saw me he didn’t need medical tests to know something was off.

“John, you don’t look right.”

I didn’t pull any punches. “To be honest,” I said, “I’m feeling kinda down.”

“In what way?”

I thought about it for a moment, then decided to tell the truth. “I really don’t feel like going on.” Even I was a bit surprised to hear those words come out of my mouth.

He looked at me carefully. “You realize that when you say that, I should send you directly to the hospital.”

“No, I’m fine.”

“You promise me you’re fine?”

“Yeah,” I said. “I’m fine.”

He wasn’t satisfied. He left the room and returned with a slip of paper. “I can tell something isn’t right, so I want you to visit this place, Westchester Medical Center, that has a psychiatric unit. Promise me you’ll go.”

I promised I would. As soon as I left his office I went directly to the WMC, met with a social worker, and told her the same thing: “I don’t feel like going on anymore.”

I wasn’t saying I wanted to kill myself. I was saying I was worn out. I didn’t want to keep doing this: waking up every day, already tired, constantly struggling to keep going, with little hope I’d ever get much better. It was exhausting, with no end in sight.

Hearing me say this, she summoned a psychiatrist, who asked me a lot of the same questions. Then he asked a new one: “Do you feel like you’re a threat to yourself?”

“No.”

“But you’ve just told two professionals that you don’t feel like going on.”

“I just don’t feel like doing this anymore,” I repeated. “I’m tired of this.”

While the doctors stepped outside to consult with each other, Wanda arrived to see me. We sat by ourselves for about an hour, not only talking about why I felt so sad but also discussing the normal husband and wife subjects: the kids, their school, all their activities.

Like many spouses of depressed people, for years Wanda had understandably tried to fix my problems with many approaches, including cheerleading: “Go out and tell yourself today is going to be a good day!” or “Think of all of the wonderful things you have to be thankful for!” She had all the best intentions, of course, but with depressed people this approach rarely helps, and sometimes it can magnify the problem. Not only do you still feel horrible, but you also feel guilty about feeling horrible. You think, “It sounds so easy. Why can’t I do it?” When Wanda realized that didn’t work, she learned to ask what I wanted, which was usually not much more than to be listened to or held. She is great at both.

When the psychiatrist came back he said, “I want you to go to the Westchester Medical Psychiatric Ward at Mt. Sinai and check in.”

“Why?” I asked.

“We want to have you under observation for a while.”

“Why?” I asked again. I wasn’t going without a fight. “I feel fine.”

With that, the psychiatrist turned a little tough. “John, all I need is two doctors’ signatures to have you admitted: mine, and the admitting physician’s. If we do that, then you’re committed, and you can’t be released without my say-so. Or you can admit yourself and sign yourself out whenever you like. So you have a choice: I can admit you, or you can do it.”

You might think, given those choices, that I’d jump at the latter and admit myself. But I wasn’t so sure. I sat in silence for a while, wondering if perhaps it might be best to have the doctor admit me so I couldn’t sign myself out until they thought I was no longer a danger to myself.

Excerpted from PLAYING HURT: MY JOURNEY FROM DESPAIR TO HOPE by John Saunders with John U. Bacon. Copyright ©2017. Available from Da Capo Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

This article was originally published on August 08, 2017.

This segment aired on August 8, 2017.