Advertisement

'One Long Night' Tells Harrowing History Of Concentration Camps

For more than 100 years, at least one concentration camp has existed somewhere on earth. A new book documents the harrowing history of concentration camps and what author Andrea Pitzer calls the "larger concentration camp tapestry" — beginning with 1890s Cuba and continuing, she says, with Guantanamo Bay today.

"When people think of camps they just think of the death camps," Pitzer says. "They think of Auschwitz, but really there's this centurylong history of all different kinds of camps: transit camps, deportation camps, internment camps, labor camps."

Here & Now's Lisa Mullins speaks with Pitzer (@andreapitzer), author of "One Long Night: A Global History of Concentration Camps."

- Find more great reads on the Here & Now bookshelf

- Scroll down to read an excerpt from "One Long Night"

Interview Highlights

On the first instance of these camps that Pitzer documents, after the sinking of the USS Maine

"In 1898, everybody remembers the [USS] Maine. 'Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain!' as the reason that the U.S. entered the Spanish-American War. But the reason the U.S. was primed to go to war was because for more than a year they had been seeing all kinds of coverage, including photos of people starving and dying, in these concentration camps. And we had been sending relief supplies, food and beans and condensed milk, to try to help these people in these camps. And we really saw what Spain was doing as an outrage. And President McKinley, when he called for war with Spain, talked about this, and he said, 'This policy of these concentration camps was not war by any civilized means. It was extermination and leads, basically, to nothing but the wilderness and the grave.' It was a very dramatic thing."

On the United States' implementation of these camps in the Philippines

"It's one of those things where, when faced with the same circumstances — when the U.S. inherited the Philippines from Spain after the war and was faced itself with an insurgency — it was very hard to ignore this new tool that they had seen lying around not that long ago. And it was an interesting argument, though, because the people against them said the president just said they were terrible in Spain, and then other people had to argue, 'Well he wasn't saying that in an official capacity.' So you get into this double speak about camps very, very early on."

On how concentration camps during World War II began

"There was that first decade or so of these colonial camps, and then they kind of fell into disrepute. Then in World War I, there was massive use of it, and you went from almost no camps in the world — by the end of World War I they were on six continents. So when the Nazi camps started, they looked very much, to outside eyes, like things that had been done in Soviet Russia or in internment camps during World War I. And a lot of people don't realize that it's really five or six years before the Nazis begin to target Jews as a group, to arrest and detain in camps. And even after that, they let almost all of them go at one point. They wanted the Jews to leave the country. But it's when the world didn't do much about it that I think is a big part of the reason that the Nazis realized they might use the camps at the heart of another kind of strategy. There was still a decided and public lack of willingness to host refugees. The Nazis had terrorized the Jews for this period during Kristallnacht in November 1938 and the world really didn't do much about it. And they realized that they could do some pretty awful things and get away with it."

Advertisement

On internment camps for Japanese-Americans, and their place in the research

"I include that as part of the larger concentration camp tapestry. When people think of camps they just think of the death camps. They think of Auschwitz, but really there's this centurylong history of all different kinds of camps: transit camps, deportation camps, internment camps, labor camps. But I would definitely put the Japanese-American internment in that category, especially since the majority of those interned were U.S. citizens after World War II."

On persecution of the Rohingya

"I actually went to Myanmar in 2015. People had been there at that point for three years, and they were quite hopeful ahead of the elections that were going to happen that fall. And, in fact, Aung San Suu Kyi did come in, but in that time after the elections, the people that I kept in touch with after I returned to the U.S. really seemed to lose hope. I think that they thought, not that she would dissolve the camps overnight, but that some kind of progress would be made. And when no progress was made I think a real general despair set in and we ended up on this path that we're on today in which the government has really been brutalizing the Rohingya.

"One of the interpreters that I was dealing with there that took me around the camps, so a Rohingya man in the camps, we were talking about it and I said, 'Couldn't you go out at night? Couldn't you make your way out of here? Why does everyone stay?' And he said that he couldn't — that even if he got out, it wouldn't matter because everybody would know he was a Rohingya. This was his hometown. He would be recognized. And I said, 'What would happen if you were caught? Would you get a trial case? What would happen?' And he said, 'If I'm caught, I don't even exist.' And that was his sense of where the people were. They were stateless, they had been stripped of everything. No one would be accountable if something happened to him."

On instances of people escaping various camps

"One of my favorite examples is in the first months of Dachau there was a communist deputy from the Reichstag who managed to escape after days and days of horrific torture, managed to sneak out with a little help through a tiny window at the top of his cell. And he got out of the country, and he sent a postcard to the guards at the camp with an expletive in it telling them exactly what they could do with themselves. But in addition, the prisoners found ways to swap bodies, they found ways to put on circuses and entertain each other. Sometimes the guards would watch, sometimes they would do this secretly. They would share recipes with each other — the amazing things people did to sustain themselves. It's pretty incredible."

On the process of documenting this history

"I felt really honored by the stories that people shared with me of the things that they had gone through and overcome, but it was also very hard. I found myself writing slower, and slower, and slower, and the book took me almost a year more than I expected it to, initially. I think it was just the the weight of this history and also that it's still going on. Guantanamo is a piece of this history, and I'm still in touch with those Rohingya people that I met in the camp. Some of them I'm still able to contact. I talk with them every week. So it's not a dead, closed history. It's an ongoing thing, and the burden of hoping that the book will do something about that — I still feel that today."

On how the Rohingya she speaks with are doing

"The ones that I'm in touch with are sort of holding fast. They are below the area that the military has sort of been burning villages in and forcing people across the border. So, for right now, that hasn't affected them much. They are still in the camp setting. But of course it makes it clear what the federal government is willing to do and what could happen at any time. So it's very precarious and nerve-wracking, but so far they haven't come to physical harm."

On conclusions about humanity and the camps

"What I've found that I think is a really important takeaway is — and it does provide a little hope — people have to be coached to do this. This is not something that arises sort of independently out of nowhere. There are always gonna be some narrow band of people who want to harm other groups, that always exists. But you really have to put the force of a government or a party or a huge institution behind it, and do sustained propaganda, to get people to go along with it — to make people hateful, but even more so, fearful enough, to allow this kind of stuff to happen. So I think the key is strengthening these institutions that don't allow this to happen. It's really, really critical for us. So it is something that, having been introduced into the world, is unlikely to leave it. But at the same time, it isn't something that's just going to automatically arise on its own."

Book Excerpt: 'One Long Night'

By Andrea Pitzer

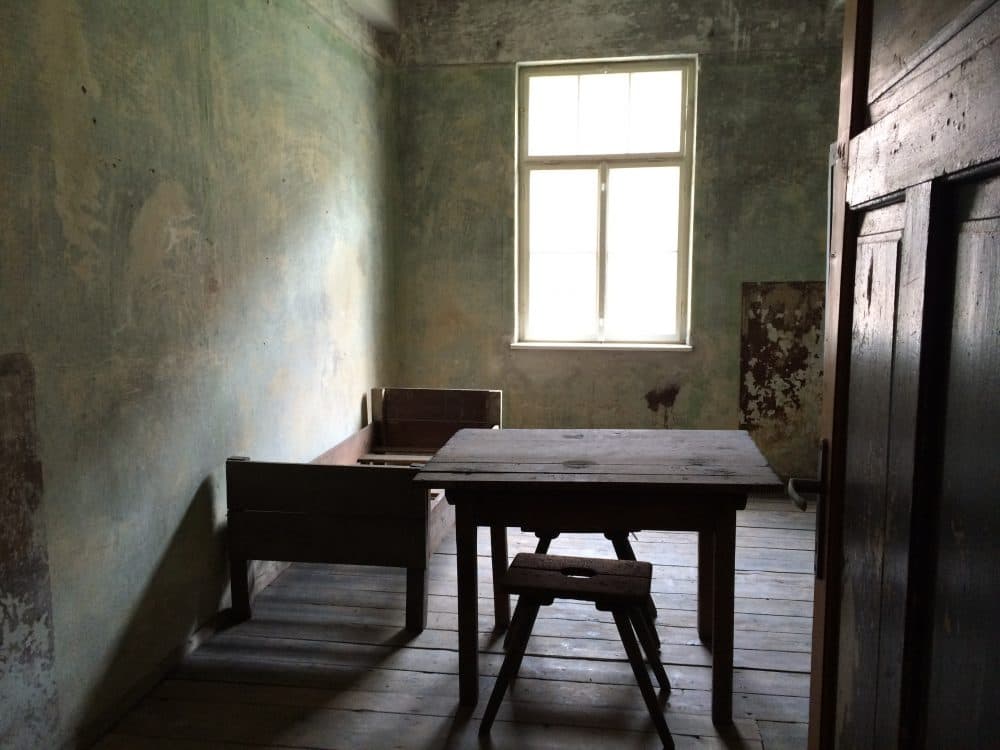

By the time she was loaded into a cattle car bound for Auschwitz, Krystyna Żywulska had endured multiple traumas in the destruction of her native Poland. Born Sonia Landau to a Jewish family in the city of Łódź, she had been forced out of law school by the Nazi invasion in 1939. After escaping the Warsaw Ghetto with her mother, she joined the Polish resistance, only to be captured. Detained with her friend Zosia, she wound up at Pawiak Prison in Warsaw. Under interrogation there, she took up a new identity: that of a Christian Pole named Krystyna Żywulska.

By 1943, Żywulska and the other prisoners in the women's section at Pawiak had years of rumors and experience to draw on. So when they were told to line up and herded into the transport cell knowing they were headed to Auschwitz, they believed they were going to their deaths. Pawiak had flea infestations, brutal daily interrogations, suicide attempts, and even killings, but it lacked the finality of Auschwitz. As they prepared to leave, a cellmate broke the gloom, saying, "At least you'll get a beautiful haircut."

They sped in trucks through the city to the train station, watching residents headed to work. Driven onto crowded cars, the prisoners waited for the train to move, and finally arrived in an open field after dark. The snarling dogs, the columns of five, the frightening march toward the barbed wire and sentry boxes on high towers visible from a distance—now she had seen a death camp. Standing next to her, Zosia, her former landlord and sister in the underground, spoke: "We've entered hell."

Żywulska was tattooed with prisoner number 55908. Her head was shaved, and she was deloused. Each detainee suddenly seemed indistinct and unrecognizable. After two days with no food or water, they were given turnip soup and four ounces of bread, a full day's ration. They ate everything without thought, as quickly as they could, which spurred the realization that they had already turned into animals.

They squatted in a large field for the day, waiting to be let into the quarantine hut to sleep. A woman who had been arrested during her wedding still wore her gown and held a bouquet as she comforted one of the guests brought to Auschwitz with her.

During her month of quarantine, Żywulska learned how to sleep in the crowded bunks and navigate the guards. She found that bread could buy a constellation of things, because there was never enough of it. Hunger at Auschwitz was a constant state. Out of earshot of camp administrators, prisoners were perpetually in conversation aimed at distracting themselves from the longing for food.

Contraband entered the camp through the prisoners who processed the belongings of Jewish transports. Family members could send parcels of approved items to prisoners, too, though Jewish prisoners were not permitted to receive packages. Żywulska imagined a magical day when she, too, might get a package from home. In the meantime, Zosia plotted how she could steal a sweater to keep her friend warm.

One morning, detainees heard a shrill whistle and were told to get to their block and stay inside. Soon afterward, a midmorning roll call was announced—but only for Jewish prisoners. Żywulska watched as women from the adjacent building were forced to line up, each one trying to avoid the front row. A familiar, hated SS executioner, unsteady on his feet and apparently drunk, proceeded to point with his cane at individual women. After they undressed, he directed each one to his right or his left. In time, it became clear that the small percentage of healthy prisoners went to the left. A thousand women in the bright sunlight stood in total silence. The prisoners in rows, the detainees still in their blocks spying through windows, the hundreds of women who had just been sent to the right—everyone understood that they had just witnessed a selection.

In the weeks that followed, Żywulska received a first parcel from her mother, which she could hardly open for weeping. Because she found roll call unbearable, she began to compose poems in her head, a thing she had never done before. Yet setbacks occurred continuously. She watched as a new acquaintance who had survived interrogations and torture at Auschwitz was taken away for good by the Gestapo. She and Zosia had to flee their barracks and hide to avoid being chosen for service in the camp brothel. Another prisoner's ill-tied diarrhea resulted in collective punishment of kneeling in the mud—which led to widespread fever. For the first time, she was separated from Zosia, who fell ill.

After nearly succumbing to work in the fields, Żywulska was assigned to the camp office. Her salvation came through assistance from a still-human kapo—one who had admired a poem she had written about morning roll call.

Assigned to process new arrivals, Żywulska learned to corral and reassure them. She could not bring herself to hit prisoners with a stick. Children came in with their mothers and lined up with them at roll call, only to be taken away for denationalization and integration into German society. A Ukrainian woman gave up hope and made a run at the barbed wire perimeter fence, knowing she would be shot.

One night during a concert performed by prisoners for administrators, kapos, and guards, Żywulska stopped in to watch a Jewish violinist from Vienna play and conduct. Just before the concert, she had seen the detainees of Block 15 kneeling for punishment. She had watched the elegant, dark-haired Greek Jews sifting through the kitchen garbage for bones to chew on. As the orchestra played, Żywulska used the distraction of the performance to slip into the typhus-ridden hospital ward and bring warm water to Zosia. Zosia, who had endured alongside her since the trip from Pawiak Prison, who had wondered if they would roast together in hell, soon died anyway.

Anything was possible at Auschwitz, and nothing made sense. Żywulska came down with typhus, too, and lay unconscious for several days. The violinist from the performance swallowed poison and killed herself. A former Soviet parachutist screamed in the night and was tied to her bed. Żywulska 's scabies began to itch, and she clawed herself, hoping to die. Yet after she was clandestinely sent medicine by a male prisoner who had kissed her during outdoor duties in her first weeks at Auschwitz, Żywulska recovered. An intervention by the same kapo who had admired her writing helped to keep her, once again, from brutal outside labor.

Soon after her recovery, a group of French women were taken in trucks to their deaths singing "La Marseillaise." A patient in the hospital hid among corpses in order to avoid being selected for death with the sickest detainees, though she would surely be chosen in the next round. Another prisoner wondered at the effort everyone was making: "Why do we want so much to live?"

After weeks in the hospital, Żywulska finally joined her new block for roll call. Back in the tiny universe of the camp, she watched a prisoner beaten for stealing potatoes. An SS man on a bicycle paused for a moment to attack an old woman. The crematorium chimney spat fire into the sky. The kapos were the same, the endless routines of the camp remained, but new prisoners lined up in place of the dead.

Excerpted from the book ONE LONG NIGHT by Andrea Pitzer. Copyright © 2017 by Andrea Pitzer. Republished with permission of Little, Brown and Company.

This article was originally published on December 29, 2017.

This segment aired on December 29, 2017.