Advertisement

In 'North,' One Ultramarathoner Takes On The Appalachian Trail — And Himself

On July 12, 2015, ultramarathoner Scott Jurek broke the speed record for running the Appalachian Trail, navigating 2,189 miles — from Georgia to Maine — in 46 days, 8 hours and 7 minutes. An enthusiastic crowd of well-wishers greeted him at the top of Maine's Mount Katahdin.

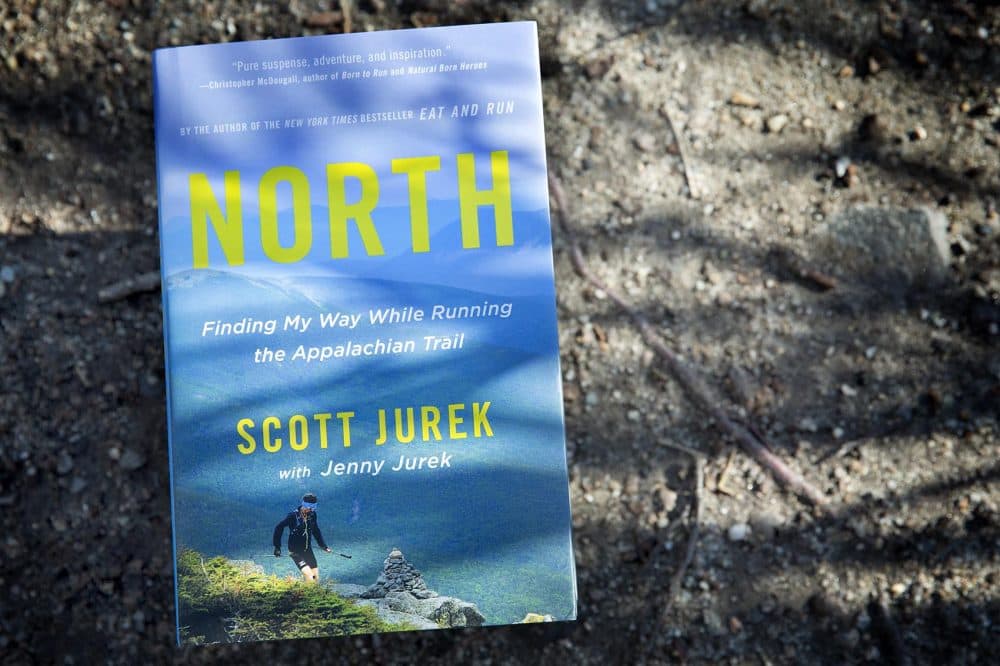

It was the culmination of a grueling endurance trial, one that he writes about with his wife Jenny in the new book "North: Finding My Way While Running the Appalachian Trail."

The two join Here & Now's Lisa Mullins to talk about the book.

- Scroll down to read an excerpt from "North"

Interview Highlights

On why he turned to the Appalachian Trail

Scott Jurek: "I think after racing for 20 years I still had a few things I wanted to do. But I was kind of spinning my wheels. I needed a new challenge, something to really kind of push me to those boundaries that other challenges had done in the past."

On Jenny's initial reaction to Scott's decision

Jenny Jurek: "It just seemed really random to me and it seemed like something really involved that would take a lot of planning. And from the previous races I'd seen, he wasn't really into it, like his heart wasn't into it, so I didn't want to put all this time and effort into doing something that he wasn't going to do wholeheartedly and with that passion. But I did realize it was a way to reignite that fire for him."

On Jenny's job on the journey

JJ: "My main job was just to be like a roving support aid station, just to provide food and water and supplies at several road crossings every day. It doesn't sound that hard, but I didn't have any cell service or GPS to really like help me with the navigation. And I had to get gas and get groceries and do his laundry. Yeah, all the little daily things that needed to get done."

"Every day there were times when I'm like, 'Why am I doing this? This is just stupid. Can I be doing this via another means or another activity or passion?' "

Scott Jurek

On Scott's experience

SJ: "Jenny definitely had the tougher job. I just had to follow those white blazes that are iconic on the Appalachian Trail, and also go up and down these mountains you're climbing each day. The trail climbs half a million feet up, half a million feet down over 2,200 miles, so a lot of days involved 10,000 to 13,000, 15,000 feet of climbing and 10,000 15,000 feet of descent. And so it definitely was challenging in its own right.

"Amidst that, we decided to open up the journey and let people in on it by occasionally posting on social media. But we also had a tracker, and people could literally follow along wherever they were. As we got along the trail, we had basically people showing up at trailheads, sometimes 10, sometimes 20, 30. And some were definitely, a little bit, probably more overbearing on Jenny because she had to answer all their questions as they were hanging out. But they also got to join me for miles, so it really was a social — and I think that's what the Appalachian Trail, it is a social trail. It was designed to connect people as well as nature."

Advertisement

On whether the other runners distracted him

SJ: "It probably wasn't the best. My buddy 'Speedgoat' who's in the book joined us two weeks in because he's like, 'Man, you guys need help.' And he was like, 'This is slowing you down. You've got to get rid of that tracker.' And for some reason, for me, I just felt like I needed that connection, and also I loved hearing the stories from people. But it did get a little old to answer all their questions, and I know some people were out there like, 'He's answering the same questions every time somebody pulls into the next trailhead, and they're joining him for the next 5 or 10 miles.' But I also got a lot of inspiration from those people."

On thinking of his mother while on the trail

SJ: "She struggled with multiple sclerosis for over 30 years, and, at a young age, I saw my mother gradually lose more and more of her physical capabilities. And she gave me perspective. It reminded me that I had two legs that, maybe weren't always in the best shape and had injuries and had their own issues, but she was a reminder that I'm able to move my body and she couldn't even do that."

On how he managed sleeping, eating and more

SJ: "It really came down to, you know, 'How am I going to fuel myself, take care of myself?' Showers got thrown out the window. Maybe I bathe in a creek, or maybe it became basically a wet towel at the end of the night. And sometimes I'd just roll into bed. Sometimes I slept on the trail, you know, on rocks, or when I would take naps for a half hour here and there. Things became more and more dire and more and more, I guess, primitive as we went along.

"I mean, every day there were times when I'm like, 'Why am I doing this? This is just stupid. Can I be doing this via another means or another activity or passion? Maybe I need to find a different hobby.' I'm not going to lie ... there were times where I told Jenny — I mean, it seemed like it was pulling us apart rather than bringing us together."

On how age factored into the decision to run the trail

SJ: "Definitely towards the end of my career, I needed something, and I also wanted to save some of these bigger challenges because I knew it would take experience, not only in sport and what I love to do, but also in life. Jenny and I had struggled with trying to raise a family, having children, and, you know, I watched Jenny almost die in my arms on our kitchen floor a year and a half prior ... and so it was one of these things where like, life is short and we need to do this now."

On Jenny's ectopic pregnancy, and experiencing the aftereffects of a miscarriage while on the trail

JJ: "I wasn't anywhere near a shower or anything that I could — or even a phone to ask my doctor what to do. So that was a little worrisome, but I wasn't about to mention it to Scott because I knew he would freak out and I knew that he would consider stopping it. We were just too close. And I just kind of risked it and hoped that everything would be OK. And it was."

On how they were able to work through issues

JJ: "I think just that we're good communicators has been really helpful."

SJ: "And understanding each other, I think that's a key part, too, is we trade off and take turns. I knew climbing Half Dome for her was a really big life goal, and so I risked some of my fears of like going up slabs of rocks and heights and all these things and doing something that I wouldn't normally like to do, but for her. And I think in a partnership or in a team atmosphere, you have to be willing to not just sacrifice but give when you need to give and then receive when you need to receive. And then like Jenny said it was communication and understanding, and, yes, there were times that we had a couple of blowouts out on the trail, but we still came together and communicated after, and I think realized why we were doing this instead of packing it up and going home, like we thought about doing as we were getting very close to the end."

Book Excerpt: 'North'

By Scott Jurek, with Jenny Jurek

DAY 33

Something was wrong. I was breathing hard. Why was my chest so tight? Had I overslept and missed a flight? Where would I have been going? Why was I so clammy? Had I fallen asleep in a pile of damp leaves? What was that snare drum beating just overhead? I felt beneath me. Wet, from head to toe. I jolted upright, waking Jenny. The beat against our roof continued. It was raining. Again.

Jenny tried to smile, but I could see the fear. She was worried about me. I learned later that she thought I had lost control of my bladder. She would have had good reason. I was losing control of my body, piece by piece by piece.

I had developed tremors in both hands. My eyes bulged. My ribs showed. Even my breath had changed. I made sounds now that I didn’t recognize, like my lungs and throat and lips had already started to devolve into something less than fully human. I looked like I’d gotten stuck halfway through a transformation in a horror film. And it wasn’t just looks. My body, which had smelled like compost just a few days earlier, now reeked like cider gone bad.

I was under attack. Rigid red bumps traced a liar’s jittery polygraph results from my neck to my ankles. In my armpits, moist, lumpy nodules. It might have been Poison Ivy, Poison Sumac, Poison Oak, or any of the other “Itchy Eight of the Appalachians,” poisonous plants that flourished in the forest and hollows and ridgelines along the 1,500 miles I had already hiked, from Georgia to Massachusetts. The bumps might have been tick, flea, or Fire Ant bites. For all I knew they might have been a reaction to the bite of one of the Brown Recluse or Black Widow spiders that wove their webs along the Appalachian Trail, webs that I was constantly breaking morning and night, that blinded me as they stuck to my eyelids and required me to raise my trekking poles out in front of me to clear the way. The same web clearing prompted my fellow thru-hikers to call me “Webwalker.”

I was covered in scrapes and falls and mystery ailments. My pain was literally embodied. It had become a part of me. Even as late as a week ago, I might have cared about the cause of the rashes. Now? I wasn’t sure what I cared about. I didn’t bother to walk behind trees when I urinated. Bathing didn’t interest me; a couple of cold baby wipes before sleep sufficed. When I was on the trail and saw someone approaching, I never knew what I was going to get. A fellow thru-hiker excited to grab a quick selfie and join me for a few miles? A patient fan at a road crossing holding a copy of my book to sign? Or maybe a trail runner who ran miles in on a side trail to offer me a chocolate bar in the middle of nowhere, perhaps doubtful (or disappointed) that the gnarled, pulpy, web-covered mess emerging from behind some trees was actually the right guy.

In many ways the Appalachian Trail was not a remote hideaway but a bustling passageway designed to connect people. I had started this journey, in part, to connect in deeper ways—with Jenny, with myself, with others. I wanted to inspire people to take chances, to test themselves. Now? Talking to strangers was more than I could handle. Inspiring anyone was out of the question. Even eating had become a chore. I tried to get by on bread soaked in olive oil, or on melted coconut milk ice cream, if Jenny could find any. Maximizing calories while minimizing chewing was the name of the game.

In the past seven days, I had slept 30 hours and had run, walked, slid, and tumbled 350 miles.

Jenny inspected me. No, I hadn’t wet the bed. It was just night sweats. I didn’t know if I was supposed to be relieved or alarmed. It didn’t matter—I was too exhausted to be either.

The rain beat grew louder. Why get up? Why put on the same wet, soggy socks and shoes? Why leave the van? I tried to come up with a reason. I didn’t. I couldn’t. I had to.

From NORTH by Scott Jurek, with Jenny Jurek. Copyright © 2018 by the authors and reprinted by permission of Little, Brown and Company.

This article was originally published on April 18, 2018.

This segment aired on April 18, 2018.