Advertisement

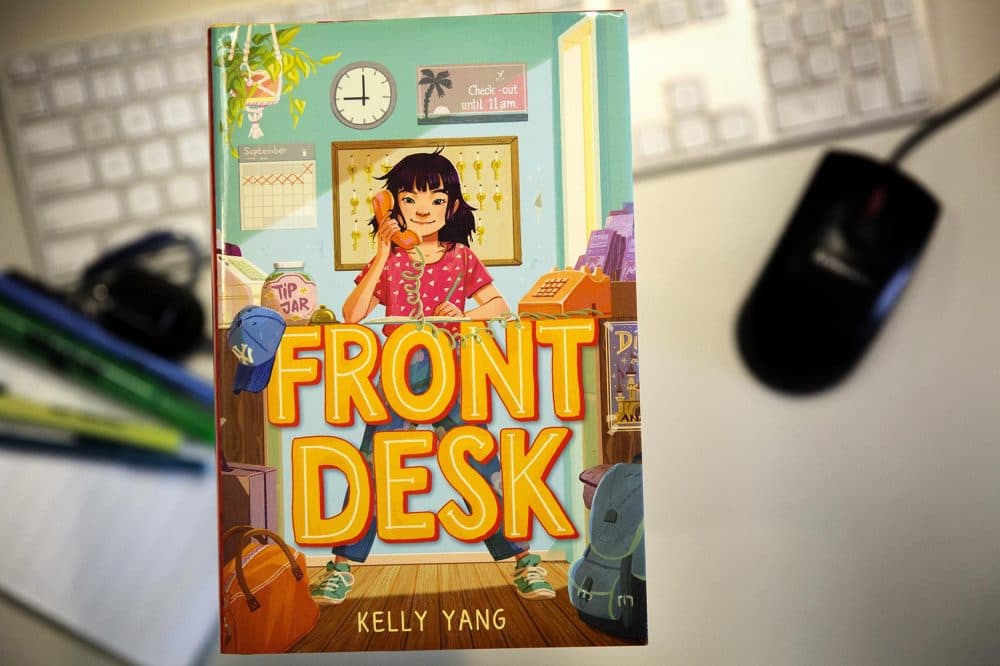

Kelly Yang Taps Memories Of Her Immigrant Childhood For YA Novel 'Front Desk'

Kelly Yang came to the United States from China at the age of 6. From ages 8-12, she helped her parents manage motels, often by taking charge of the front desk.

She's now published the kids' book "Front Desk," which was inspired by her own experiences.

Here & Now's Femi Oke speaks with Yang (@kellyyanghk) about the book and her thoughts on the current immigration crisis.

Book Excerpt: 'Front Desk'

by Kelly Yang

My parents told me that America would be this amazing place where we could live in a house with a dog, do whatever we want, and eat hamburgers till we were red in the face. So far, the only part of that we’ve achieved is the hamburger part, but I was still holding out hope. And the hamburgers here are pretty good.

The most incredible burger I’ve ever had was at the Houston space center last summer. We weren’t planning on eating there — everybody knows museum food is fifty thousand times more expensive than outside food. But one whiff of the sizzling bacon as we passed by the café and my knees wobbled. My parents must have heard the howls of my stomach, because the next thing I knew, my mother was rummaging through her purse for coins.

We only had enough money for one hamburger, so we had to share. But, man, what a burger. It was a mile high with real bacon and mayonnaise and pickles!

My mom likes to tease that I devoured the whole thing in one gulp, leaving the two of them only a couple of crumbs. I’d like to think I gave them more than that.

Advertisement

The other thing that was great about that space center was the free air conditioning. We were living in our car that summer, which sounds like a lot of fun but actually wasn’t, because our car’s AC was busted. So after the burger, my dad parked himself in front of the vent and stayed there the entire rest of the time. It was like he was trying to turn his fingers into Popsicles.

My mom and I bounced from exhibit to exhibit instead. I could barely keep up with her. She was an engineer back in China, so she loves math and rockets. She oohed and aahed over this module and that module. I wished my cousin Shen could have been there. He loves rockets too.

When we got to the photo booth, my mother’s face lit up. The booth took a picture of you and made it look like you were a real astronaut in space. I went first. I put my head where the cardboard cutout was and smiled when the guy said, “Cheese.” When it was my mom’s turn to take her photo, I thought it would be funny to jump into her shot. The result was a picture of her in an astronaut suit, hovering over Earth, and me standing right next to her in my flip-flops, doing bunny ears with my fingers.

My mother’s face crumpled when she saw her picture. She pleaded with the guy to let her take another one, but he said, “No can do. One picture per person.” For a second, I thought she was going to cry.

We still have the picture. Every time I look at it, I wish I could go back in time. If I could do it all over again, I would not photobomb my mom’s picture. And I’d give her more of my burger. Not the whole thing but definitely some more bites.

...

At the end of that summer, my dad got a job as an assistant fryer at a Chinese restaurant in California. That meant we didn’t have to live in our car anymore and we could move into a small one-bedroom apartment. It also meant my dad brought home fried rice from work every day. But sometimes, he’d also bring back big ol’ blisters all up and down his arm. He said they were just allergies. But I didn’t think so. I think he got them from frying food all day long in the sizzling wok.

My mom got a job in the front of the restaurant as a waitress. Everybody liked her, and she got great tips. She even managed to convince the boss to let me go with her to the restaurant after school, since there was nobody to look after me.

My mother’s boss was a wrinkly white-haired Chinese man who reeked of garlic and didn’t believe in wasting anything — not cooking oil, not toilet paper, and certainly not free labor.

“You think you can handle waitressing, kid?” he asked me.

“Yes, sir!” I said. Excitement pulsated in my ear. My first job! I was determined not to let him down.

There was just one problem — I was only nine then and needed two hands just to hold one dish steady. The other waitresses managed five plates at a time. Some didn’t even need hands — they could balance a plate on their shoulder.

When the dinner rush came, I too loaded up my carrying tray with five dishes. Big mistake. As my small back gave in to the mountainous weight, all my dishes came crashing down. Hot soup splashed onto customers, and fried prawns went f lying across the restaurant.

I was fired on the spot and so was my mother. No amount of begging or promising to do the dishes for the next gazillion years would change the owner’s mind. The whole way home, I fought tears in my eyes.

I thought of my three cousins back home. None of them had ever gotten fired before. Like me, they were only children as well. In China, every child is an only child, ever since the government decided all families are allowed only one. Since none of us had siblings, we were our siblings. Leaving them was the hardest part about leaving China.

I didn’t want my mom to see me cry in the car, but eventually that night, she heard me. She came into my room and sat on my bed. “Hey, it’s okay,” she said in Chinese, hugging me tight. “It’s not your fault.”

She wiped a tear from my cheek. Through the thin walls, I could hear the sounds of husbands and wives bickering and babies wailing from the neighboring apartments, each one as cramped as ours.

“Mom,” I asked her, “why did we come here? Why did we come to America?” I repeated.

My mother looked away and didn’t say anything for a long time. A plane flew overhead, and the picture frames on the wall shook.

She looked in my eyes.

“Because it’s freer here,” she finally said, which didn’t make any sense. Nothing was free in America. Everything was so expensive.

“But, Mom — ”

“One day, you’ll understand,” she said, kissing the top of my head. “Now go to sleep.”

I drifted to sleep, thinking about my cousins and missing them and hoping they were missing me back.

...

After my mother got fired from the restaurant, she got very serious about job hunting. She called it getting back on her horse. It was 1993 and she bought every Chinese newspaper she could f ind. She pored over the jobs section with a magnifying glass like a scientist. That’s when she came across an unusual listing.

A man named Michael Yao had put an ad out in the Chinese newspaper looking for an experienced motel manager. The ad said that he owned a little motel in Anaheim, California, and he was looking for someone to run the place. The job came with free boardng too! My mother jumped up and grabbed the phone — our rent then cost almost all my dad’s salary. (And who said things in America were free?)

To her surprise, Mr. Yao was equally enthusiastic. He didn’t seem to mind that my parents weren’t experienced and really liked the fact that they were a couple.

“Two people for the price of one,” he joked in his thick Taiwanese-accented Mandarin when we went over to his house the next day.

My parents smiled nervously while I tried to stay as still as I could and not screw it up for them, like I’d screwed up my mother’s restaurant job. We were sitting in the living room of Mr. Yao’s house, or rather, his mansion. I made myself look at the f loor and not stare at the top of Mr. Yao’s head, which was all shiny under the light, like it had been painted in egg white.

The door opened, and a boy about my age walked in. He had on a T-shirt that said I don’t give a, and underneath it, a picture of a rat and a donkey. I raised an eyebrow.

“Jason,” Mr. Yao said to the boy. “Say hello.” “Hi,” Jason muttered.

My parents smiled at Jason.

“What grade are you in?” they asked him in Chinese.

Jason replied in English, “I’m going into fifth grade.”

“Ah, same as Mia,” my mom said. She smiled at Mr. Yao. “Your son’s English is so good.” She turned to me. “Hear that, Mia? No accent.”

My cheeks burned. I felt my tongue in my mouth, like a limp lizard.

“Of course he speaks good English. He was born here,” Mr. Yao said. “He speaks native English.”

Native. I mouthed the word. I wondered if I worked really hard, would I also be able to speak native English one day? Or was that something completely off-limits for me? I looked over at my mom, who was shaking her head. Jason disappeared off to his room, and Mr. Yao asked my parents if they had any questions.

“Just to make sure, we can live at the motel for free?” my mom asked.

“Yes,” Mr. Yao said.

“And . . . what about . . .” My mom struggled to get the words out. She shook her head, embarrassed to say it. “Will we get paid?”

“Oh, right, payment,” Mr. Yao said, like it hadn’t dawned on him at all. “How’s five dollars a customer?”

I glanced at my mom. I could tell that she was doing math in her head because she always got this dreamy smile on her face.

“Thirty rooms at five dollars a room — that’s a hundred and fifty dollars a night,” my mom said, her eyes widening. She looked at my dad. “That’s a lot of money!”

It was a humongous amount of money. We could buy hamburgers every day, one for each of us — we wouldn’t even need to share!

“When can you start?” Mr. Yao asked.

“Tomorrow,” my mom and dad blurted out at the exact same time.

Mr. Yao laughed.

As my parents got up to shake his hands, Mr. Yao muttered, “I have to warn you. It’s not the nicest motel in the world.”

My parents nodded. I could tell it made no difference to them what the motel looked like. It could look like the inside of a Greyhound bus toilet for all we cared; at $150 a day plus free rent, we were in.

Excerpted from the book FRONT DESK by Kelly Yang. Copyright © 2018 by Kelly Yang. Republished with permission of Arthur A. Levine Books, an imprint of Scholastic.

This segment aired on June 19, 2018.