Advertisement

In Antebellum New Orleans, Immunity From Yellow Fever Was A Form Of Privilege. Could That Happen With COVID-19?

As the White House considers how to reopen the economy, the question of immunity looms large.

Should people who have recovered from COVID-19 be allowed to go back to work while the rest of the country waits for a vaccine? Who would this help and whom might this hurt?

Katherine Olivarius, an assistant history professor at Stanford University, says there are no easy answers, but the antebellum South might hold some clues — and a warning.

Olivarius’ research focuses on yellow fever, a mosquito-borne disease that she says used to hit the South during the 1800s every three summers. Yellow fever then was far more deadly than the coronavirus today — half of those who got it died, she writes.

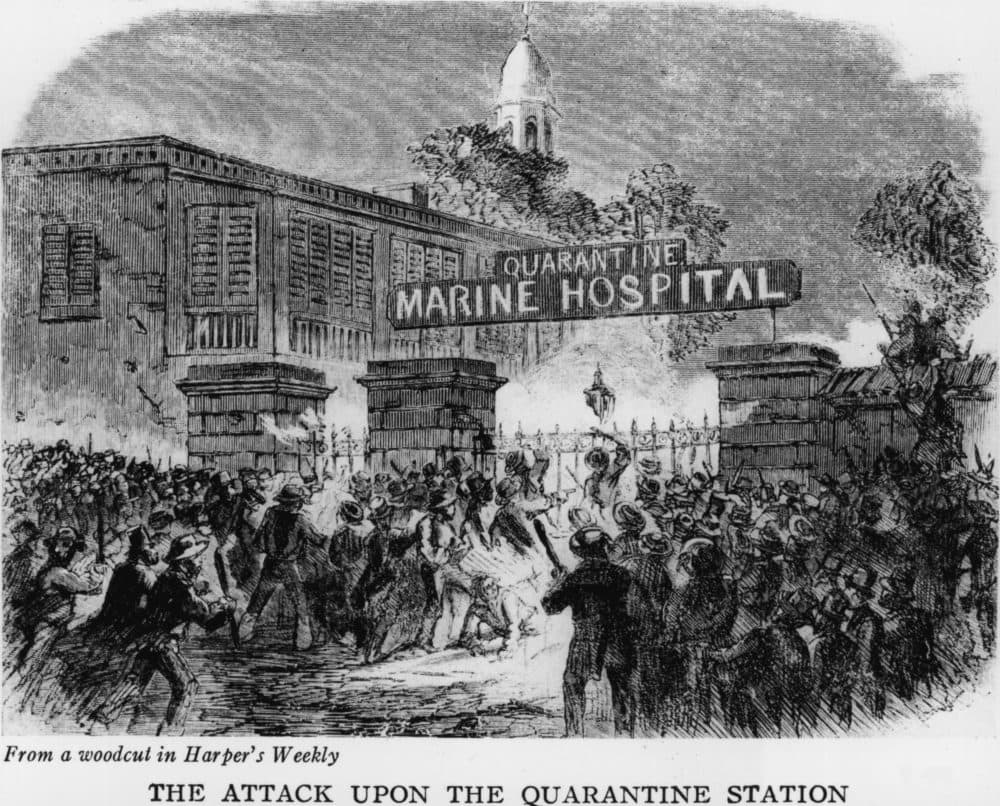

In the six decades between the Louisiana Purchase and the Civil War, New Orleans alone went through 22 epidemics where about 10% of the population succumbed each year.

In this environment, Olivarius says, immunity became a form of privilege that sat atop more familiar forms like race and class. To become immune, or “acclimated,” as the locals called it, was “the baptism of citizenship.”

Foreigners, mostly white male immigrants from the North, were unable to get jobs or life insurance without proving they were acclimated to yellow fever. Nor could they live in certain neighborhoods, or even think of marrying; many white fathers forbade their daughters from becoming engaged to unacclimated men because it was too risky.

All of this shows, Olivarius says, how important immunity was if you wanted to participate in any aspect of the economic, social or political life of New Orleans. This led many immigrants to infect themselves on purpose, sometimes by jumping onto a bed where a friend had just died, she says.

Grimmer still, Olivarius says, immunity from yellow fever also exacerbated the racial hierarchies of the South. White slave owners routinely repeated the myth that black people were innately immune to yellow fever — a haunting echo of similar myths that circulated at the outbreak of the coronavirus.

Advertisement

Whites used this falsehood to justify why black people should do the hardest forms of labor — draining swamps, working in the fields and fixing the levies where the thickest clouds of mosquitos swarmed.

To fully understand just how valuable being acclimated was, Olivarius says, look no further than the auction block. There, being immune to yellow fever would drive up the price of an enslaved person by 25-50%.

Fast forward to today and the parallels are hard to miss, Olivarius says. Early data shows black Americans are dying at higher rates from COVID-19, and many immigrants who pick our food have transformed into “essential” laborers overnight. Meanwhile, the elites retreat to the safety of their homes, and even second homes where they can practice social distancing.

Olivarius says that while she hopes immunity from COVID-19 becomes a productive, positive part of our recovery — with immune individuals taking care of the elderly or helping to do more tests, for example — she’s also afraid immunity could exacerbate the inequalities already present in our society, just as it did in New Orleans more than a century ago.

“My concern is that the impetus will be on individuals” to seek out immunity so they can provide for their families, she says.

And, like the immigrants jumping onto the sick bed, Olivarius fears it will be the most vulnerable among us leaping first.

Cassady Rosenblum produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Tinku Ray. Rosenblum also adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on April 17, 2020.