Advertisement

Covering Climate Now: COP26

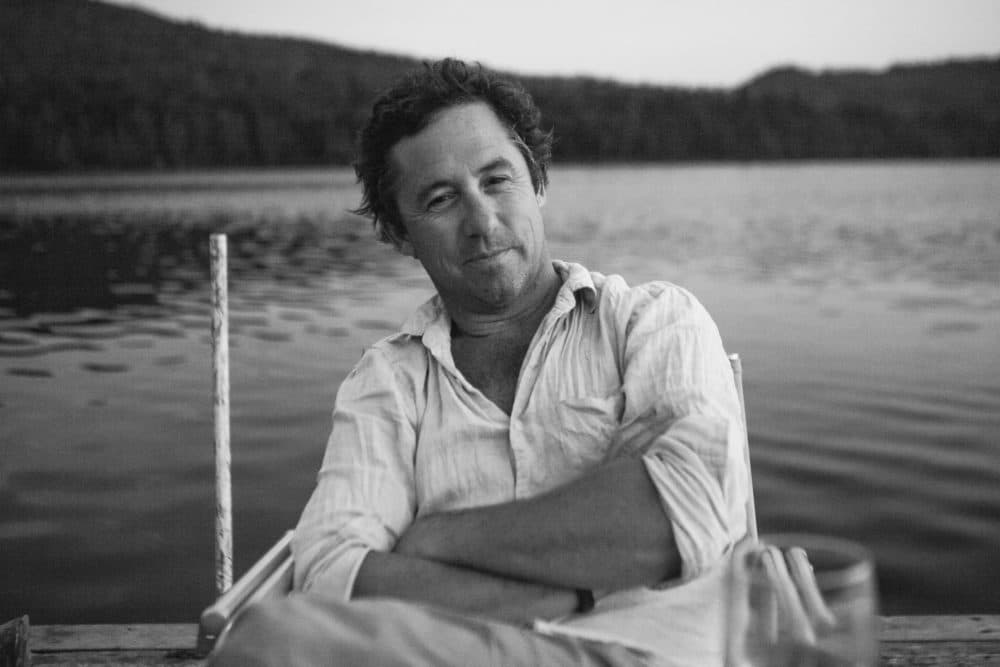

Journalist Porter Fox goes to the coldest places on Earth to explore climate change

Editor's note: This segment was rebroadcast on July 21, 2022. Find that audio here.

Here & Now's Peter O'Dowd speaks with Porter Fox about his new book, "The Last Winter: The Scientists, Adventurers, Journeymen, and Mavericks Trying to Save the World." The book documents retreating snow and ice around the planet.

This story is part of Covering Climate Now, a project aimed at strengthening the media’s focus on the climate crisis. WBUR is one of 400+ news organizations that have committed to a week of heightened coverage around the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow. Check out all our coverage here.

Book excerpt: 'The Last Winter'

By Porter Fox

Measuring the pace of an object that moves so incrementally that its name is synonymous for slow can be a monotonous task. But pace depends on perspective, and in the realm of deep time, glaciers are devastatingly dynamic. They dug the Great Lakes a quarter mile deep, flattened the Northern Plains, and shaped most major river systems and mountain ranges in North America. Glaciers carved the coasts as well and pushed till hundreds of miles, creating the foundations for entire ecosystems across the planet. If you could watch two million years of the earth’s history in fast-forward, ice’s dominion over terra firma — think waves crashing on a shoreline — would be terrifying.

By the 2000s, it was clear that ice in the Cascades did not have long to live. Glaciers across the region’s parks, from the Olympic Peninsula to the North Cascades, had always reacted differently to various climate events. By 2007, every glacier in the park was moving in unison for the first time: backward. The rate of recession increased as the decade wore on — radically on some glaciers that had hardly moved in a century. Even with an increase in precipitation during some winters, warm air over the region continued to melt the ice. “One of the most striking things you see are lakes now where there used to be glaciers,” Dr. Jon Riedel said. “They create these depressions in the side of the mountains as they advance, then, as the glaciers melt, lakes form under them and the glacier eventually collapses into the lake.”

Advertisement

Riedel led me to a covered porch and two rocking chairs. Winter was still a month away, but there was a chill in the air. He and Sarah spent most of their time in Anacortes, Washington, now, where their girls had gone to school. The Marblemount house was furnished but otherwise empty. No photos on the refrigerator door, no dishes in the sink, no mail stacked on the kitchen table. Riedel leaned back in his chair and listed the status of each glacier he monitored. Most were listed among the fastest-melting glaciers in the world. It takes a massive climatic change to sync up the flow of billions of tons of ice, and to do it in such a short timeline — in Riedel’s lifetime — was unthinkable.

The ramifications were many. For hundreds of millions of years, ice and snow regulated the earth’s climate by reflecting 80 percent of solar radiation that hit them back into space. When they melt, the exposed dark ground and water absorb sunlight and radically increase warming. Scientists call a surface’s ability to reflect solar radiation its albedo, from the Latin term albus, meaning “white” or “whiteness.” The melting glaciers were causing a rapid feedback loop of diminishing albedo. There are other feedback loops too, such as how a lack of sea ice in the Arctic changes weather patterns around the world and how trillions of gallons of water from melting land ice can block major ocean currents like the Gulf Stream — altering the climate of entire continents while raising sea levels. I had told the story of skiing and winter hundreds of times, and even the future of snow in a warmer world, but I had somehow not connected all the dots until a few years ago. We know it is going to get warmer. We know that part or all of the cryosphere will melt. But what does that actually mean to places far from a ski slope — in Los Angeles? Paris? New Delhi? My home in New York?

Things don’t just happen in nature. Cascades happen as interrelated systems crash, in the way that a single falling stone starts an avalanche. Melting the cryosphere was like dropping a boulder into that avalanche field. Things start to fall with it. “It’s a pretty wicked series of things that all sort of tie together, and then throw in a tipping point or thresholds on top of that,” Riedel said. “And you’ve got to believe we’re approaching, whether it’s the Arctic losing its sea ice or the Greenland Ice Sheet disappearing, many of these feedback mechanisms that could accelerate climate change.”

Another way to envision the coming transformation, Riedel said, is to think of it in terms of seasons. The Northern Hemisphere enters winter when the planet tips back and half of its land surface is covered with snow and ice. Since the 1800s, two centuries of industrialization have erased thousands of years of deep freeze and created an antithetical trend — an epic summer that is overtaking winter. “It’s all tied to the seasons,” he said. “What we’re seeing now is the growth of the summer season — and the fire season — so the forests are drying out earlier, again, due to loss of snow but also due to warmer air temperatures. The loss of snow affects the water supply, but it also affects the ecology in so many ways — not just forest fires but the growing season, pollination, hydropower, freshwater supply, river habitat, and myriad other effects because climate affects everything.”

This has happened before. “Hothouse earth” three million years ago saw palm trees, giant beavers, and camels living quite happily in the Arctic. The difference being that those climate shifts were kicked off by natural forces like volcanoes and giant methane releases that typically took thousands of years to play out. The speed of current climate change has been seen only a few times in the past, and the effects will be drastic, Riedel said. Another interesting point, he added, was how we have oriented ourselves, placed our cities, established our diet and agricultural practices rigidly within the parameters of the current climate — which will no longer be here in a few decades. Riedel was saying this: the snow and ice we both loved and had explored for most of our lives was more than a boulder teetering on top of a mountain. It was the mountain.

Excerpted from THE LAST WINTER by Porter Fox. Copyright © 2021 by Porter Fox. Used with permission of Little Brown and Company. New York, NY. All rights reserved.

This segment aired on November 9, 2021.