Advertisement

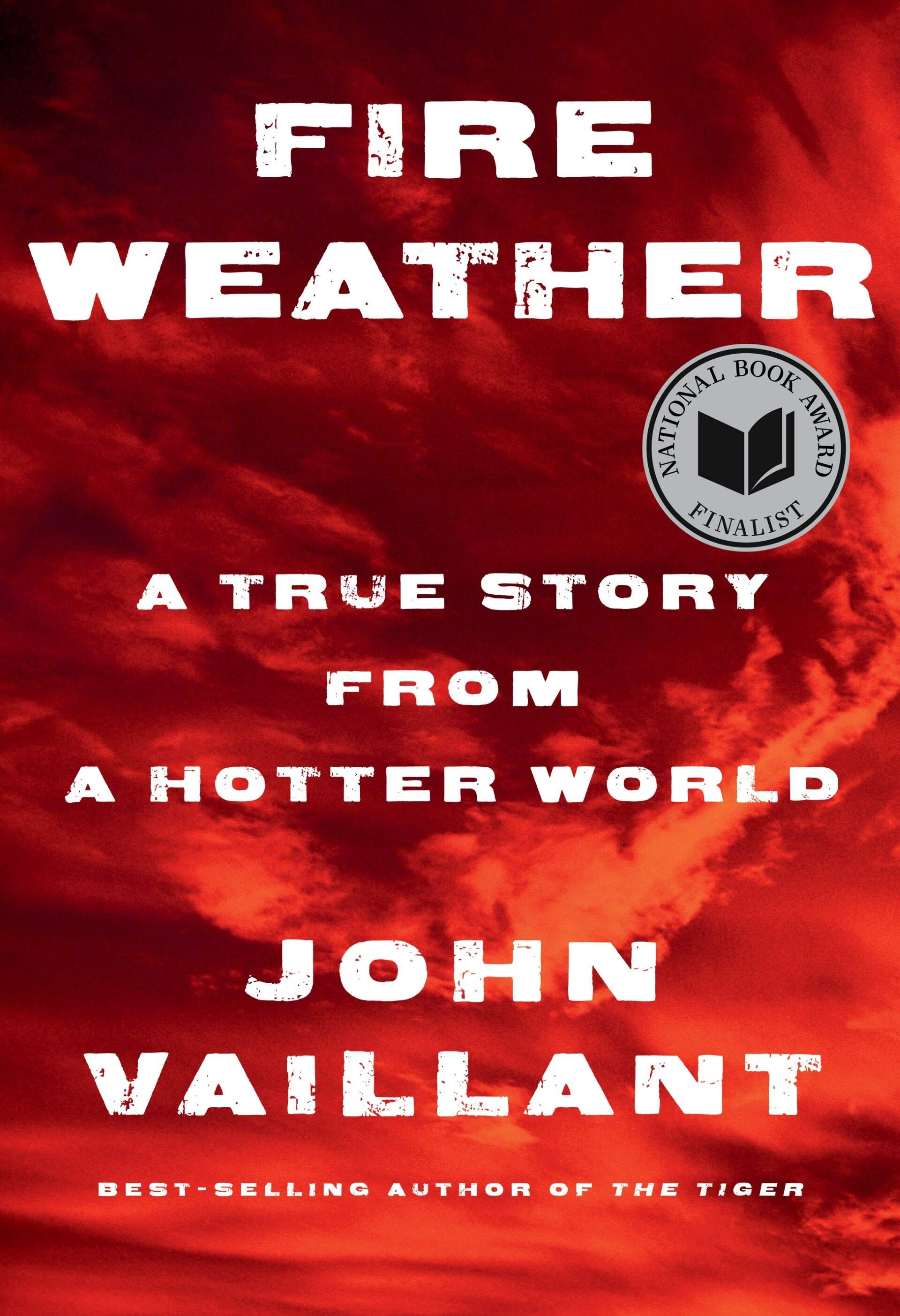

National Book Award finalist 'Fire Weather' explores the links between fire and our warming planet

Editor's note: This segment was rebroadcast on May 27, 2024. Click here for that audio.

Host Peter O'Dowd speaks with journalist and author John Vaillant about his book "Fire Weather: A True Story from a Hotter World," which looks at the devastating 2016 fire in Fort McMurray Canada and what it shows about how climate change is shaping fires present and future.

Book excerpt: 'Fire Weather: A True Story from a Hotter World'

By John Vaillant

PROLOGUE

On a hot afternoon in May 2016, five miles outside the young petro-city of Fort McMurray, Alberta, a small wildfire flickered and ventilated, rapidly expanding its territory through a mixed forest that hadn’t seen fire in decades. This fire, farther off than the others, had started out doing what most human-caused wildfires do in their first hours of life: working its way tentatively from the point of ignition through grass, forest duff, and dead leaves—a fire’s equivalent to baby food. These fuels, in combination with the weather, would determine what kind of fire this one was going to be: a creeping, ground-level smolder doomed to smother in the heavy dew of a cool and windless spring night, or something bigger, more durable, and dynamic—a fire that could turn night into day and day into night, that could, unchecked and all-consuming, bend the world to its will.

Advertisement

It was early in the season for wildfires, but crews from the Wildfire Division of Alberta’s Ministry of Forestry and Agriculture were on alert. As soon as smoke was spotted, wildland firefighters were dispatched, supported by a helicopter and water bombers. First responders were shocked by what they saw: by the time a helicopter with a water bucket got over it, the smoke was already black and seething, a sign of unusual intensity. Despite the firefighters’ timely intervention, the fire grew from 4 acres to 150 in two hours. Wildfires usually settle down overnight, as the air cools and the dew falls, but by noon the following day this one had expanded to nearly 2,000 acres. Its rapid growth coincided with a rash of broken temperature records across the North American subarctic that peaked at 90°F on May 3 in a place where temperatures are typically in the 60s. On that day, Tuesday, a smoke- and wind-suppressing inversion lifted, winds whipped up to twenty knots, and a monster leaped across the Athabasca River.

Within hours, Fort McMurray was overtaken by a regional apocalypse that drove serial firestorms through the city from end to end—for days. Entire neighborhoods burned to their foundations beneath a towering pyrocumulus cloud typically found over erupting volcanoes. So huge and energetic was this fire-driven weather system that it generated hurricane-force winds and lightning that ignited still more fires many miles away. Nearly 100,000 people were forced to flee in what remains the largest, most rapid single-day evacuation in the history of modern fire. All afternoon, cell phones and dashcams captured citizens cursing, praying, and weeping as they tried to escape a suddenly annihilating world where fists of heat pounded on the windows, the sky rained fire, and the air came alive in roaring flame. Choices that day were stark and few: there was Now, and there was Never.

A week later, the fire’s toll conjured images of a nuclear blast: there was not just “damage,” there was total obliteration. Trying to articulate what she saw during a tour of the fire’s aftermath, one official said, “You go to a place where there was a house and what do you see on the ground? Nails. Piles and piles of nails.” More than 2,500 homes and other structures were destroyed, and thousands more were damaged; 2,300 square miles of forest were burned. By the time the first photos were released, the fire had already belched 100 million tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, much of it from burning cars and houses. The Fort McMurray Fire, destined to become the most expensive natural disaster in Canadian history, continued to burn, not for days, but for months. It would not be declared fully extinguished until August of the following year.

Wildfires live and die by the weather, but “the weather” doesn’t mean the same thing it did in 1990, or even a decade ago, and the reason the Fort McMurray Fire trended on newsfeeds around the world in May 2016 was not only because of its terrifying size and ferocity, but also because it was a direct hit—like Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans—on the epicenter of Canada’s multibillion-dollar petroleum industry. That industry and this fire represent supercharged expressions of two trends that have been marching in lockstep for the past century and a half. Together, they embody the spiraling synergy between the headlong rush to exploit hydrocarbons at all costs and the corresponding increase in heat-trapping greenhouse gases that is altering our atmosphere in real time. In the spring of 2016, halfway through the hottest year of the hottest decade in recorded history, a new kind of fire introduced itself to the world.

“No one’s ever seen anything like this,” Fort McMurray’s exhausted and grieving fire chief said on national TV. “The way this thing happened, the way it traveled, the way it behaved—this is rewriting the book.”

Excerpted from "Fire Weather: A True Story from a Hotter World" by John Vaillant. Published June 6, 2023, by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2023 by John Vaillant.

This segment aired on November 6, 2023.