Advertisement

Even With Strong New Evidence, It Was A Struggle For Pittsfield Man To Get New Trial

Resume

The second of a two-part report. Here's Part 1.

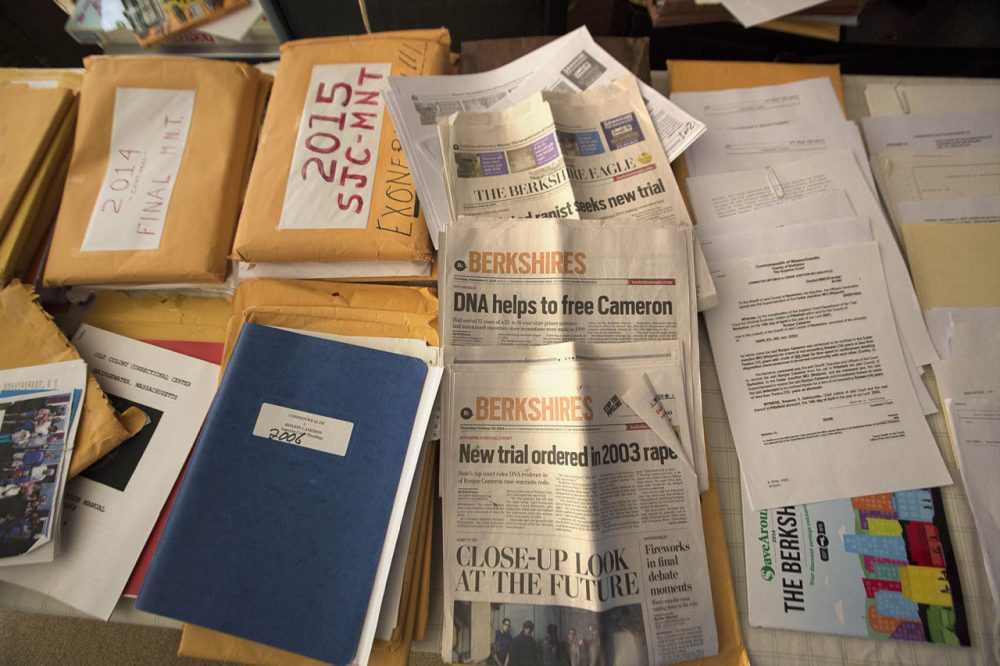

PITTSFIELD, Mass. — In jail and awaiting trial in 2003, defendant Ronjon Cameron, of Pittsfield, expected to be cleared when DNA testing showed no link between him and the rape he had been charged with committing.

But the prosecution used what it called the “inconclusive” results to win his conviction. Still proclaiming his innocence, Cameron went to prison for a term of 12 to 16 years. He had served nine years when a new DNA test showed the evidence presented by the prosecution was wrong. The prosecution had put female DNA into evidence as male DNA. So that “inconclusive” result presented at trial did not implicate Cameron at all.

Once again Cameron expected to get out. But he remained in prison three more years.

“If you have a trial and things go wrong, once you’re convicted, undoing it is very, very difficult,” said attorney Laura Edmonds, who knows how difficult it is to undo a criminal conviction. She has worked on Cameron's case for the last six years.

“It is virtually impossible," she said. "The burden really has shifted, cause now [as the defendant] you really do have to prove your innocence.”

An Uphill Climb For A New Trial

For Edmonds, winning a new trial for Cameron meant overcoming a judge’s error, the ineffectiveness of the trial attorney and the misuse of evidence by the prosecution.

Arrested in 1999, Cameron denied ever having sexual relations with the woman who accused him of rape, so DNA testing of the woman’s undergarments was conducted to show if he ever had.

It revealed two sources of male DNA, according to the government’s expert testimony. The so-called primary source did not match Cameron’s DNA, so he was excluded as the “donor." Test results for the so-called secondary source of DNA were deemed “inconclusive." But despite that designation, the government expert went ahead and told the jurors it did not exclude Cameron (just as it did not include him, either).

“This is a big deal,” Edmonds detailed in a recent interview. “At a very fundamental level, [the jurors] were given incorrect information.”

One of Edmonds’ arguments for a new trial was that Cameron’s defense attorney at his trial gave "ineffective assistance of counsel." He never hired a DNA expert for the defense. And he never ordered a more discriminating DNA test than the narrow one used by the prosecution. In fact, a version of the test the lawyer could have ordered showed in 2012 that the second source of DNA didn't come from a man at all. It was from a woman. After nine years in prison, Cameron figured he was getting out.

“His reaction was, I think, ‘Finally someone is going to hear me,’ ” Edmonds said. “I actually thought that maybe even the prosecution would agree to a new trial.”

But there was no chance of that, not according to Berkshire District Attorney David Capeless, who used a line popularly associated with Donald Rumsfeld: “The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence."

In other words, just because there's no DNA evidence that shows Cameron did it, that does not mean Cameron didn't do it. (Capeless had used the same argument in a notorious triple-homicide case he successfully prosecuted in 2014.)

“We had confidence in the victim and her credibility,” Capeless said in an interview. “She knew him and she said, ‘That's the man that raped me.' "

When Edmonds filed motions for a new trial, Capeless argued against one. He said it was never a case about DNA; it was a case about credibility, and the jurors found the accuser more credible than the accused.

But the prosecution had relied upon DNA, using it to bolster the accuser's credibility.

According to forensic expert and attorney Thomas Workman, who teaches a law school course on criminal evidence, bolstering her credibility went something like this at trial: “The prosecutor said you can use the DNA to know there was a secondary source. They can’t say for sure it was him. But we do know there was somebody else. The male DNA in her undergarments confirms that. And she says it was him.”

With the stunning new DNA evidence that emerged in 2012, however, the accuser's credibility came in for questioning.

When asked if his office made any attempt to question the accuser or to check her credibility after learning the results of the DNA test in 2012, Capeless answered: “No, because as I said, it now raises even higher the question of whether or not the evidence that was used for the DNA testing in fact was related to the crime.”

The district attorney now raises the possibility that the alleged victim might have given the wrong underpants to the detective for testing. He also raises the possibility that the reason Cameron’s DNA was not found in the accuser’s underwear is because the defendant did not ejaculate.

“There was some question, first off, in her mind whether he had in fact ejaculated,” Capeless said.

Yet that was not what the accuser told the doctor in the hospital in 1999. She said Cameron had ejaculated. Then she told the detective she believed he had. At trial, and after the first DNA results showed no link to Cameron, Edmonds pointed out, Cameron’s accuser did become more equivocal. But she still testified in the affirmative.

Edmonds said she was stunned by the district attorney’s unwillingness to reconsider the integrity of the conviction in light of the new evidence.

“I thought they would recognize more easily that something went wrong here, and that their job is to do justice," Edmonds said. "They have a responsibility in terms of the interests of justice to have a good conviction -- not just any conviction, but a solid conviction.”

Yet the district attorney opposed all Cameron's motions for a new trial and, more importantly, the courts all agreed until 2015. They ruled that judges’ errors had been harmless, the admission of old DNA evidence had not prevented a fair trial, and the new DNA evidence that was revealed in 2012 fell “far short of exonerating him.”

“So much hope,” Cameron's daughter Leah recalled about the discouraging legal setbacks for her family. “So much hope, every time it went somewhere, ‘Somebody’s going to realize how wrong this is, one of these courts is going to basically see it.’ ”

The only court to see it was the state's highest court. And when the Supreme Judicial Court took the case up last fall, it saw issues quite differently than the lower courts had.

The SJC saw how the prosecution had used the erroneous old DNA evidence against Cameron at trial. It had tipped the balance against the defendant, the SJC ruled. And, like the toll of a bell, the damage could not be undone or “cured” by what followed. The high court saw the importance of the new DNA evidence “that conclusively excludes the defendant as a possible donor…”

In ruling the Cameron must have a new trial, the SJC stated “[the new evidence] would have cast doubt on the credibility of the complainant and rendered the Commonwealth’s strongest corroborative evidence inadmissible. Had the new evidence been available at trial, there is a substantial risk that the jury would have reached a different conclusion.”

'Unresponsive' Victim, And A Dropped Case

A month after the decision, on the day before Thanksgiving and with no public statement, the Berkshire DA's office quietly filed a document known as a "null pros" to drop the case altogether. There would be no trial.

“We were and remain prepared, well, we were prepared to re-prosecute the case,” District Attorney Capeless said in his office a few days later. “We were just unable to because we did not have the victim to testify.”

The DA called the alleged victim "unresponsive" to efforts to make contact with her.

But her address is known -- she receives public assistance -- and her neighbors confirm she resides in the apartment where her name is on the mailbox, within an hour's drive of Pittsfield. She’s easily found on social media.

"Well, all our efforts in contacting her were unsuccessful,” Capeless said.

Across Massachusetts and on a daily basis, state police detectives assigned to district attorneys and local uniform police officers knock on the doors of victims and witnesses to persuade or to compel them to testify. Their job is to find people. In this case it's not clear the prosecution did more than send a couple of certified letters.

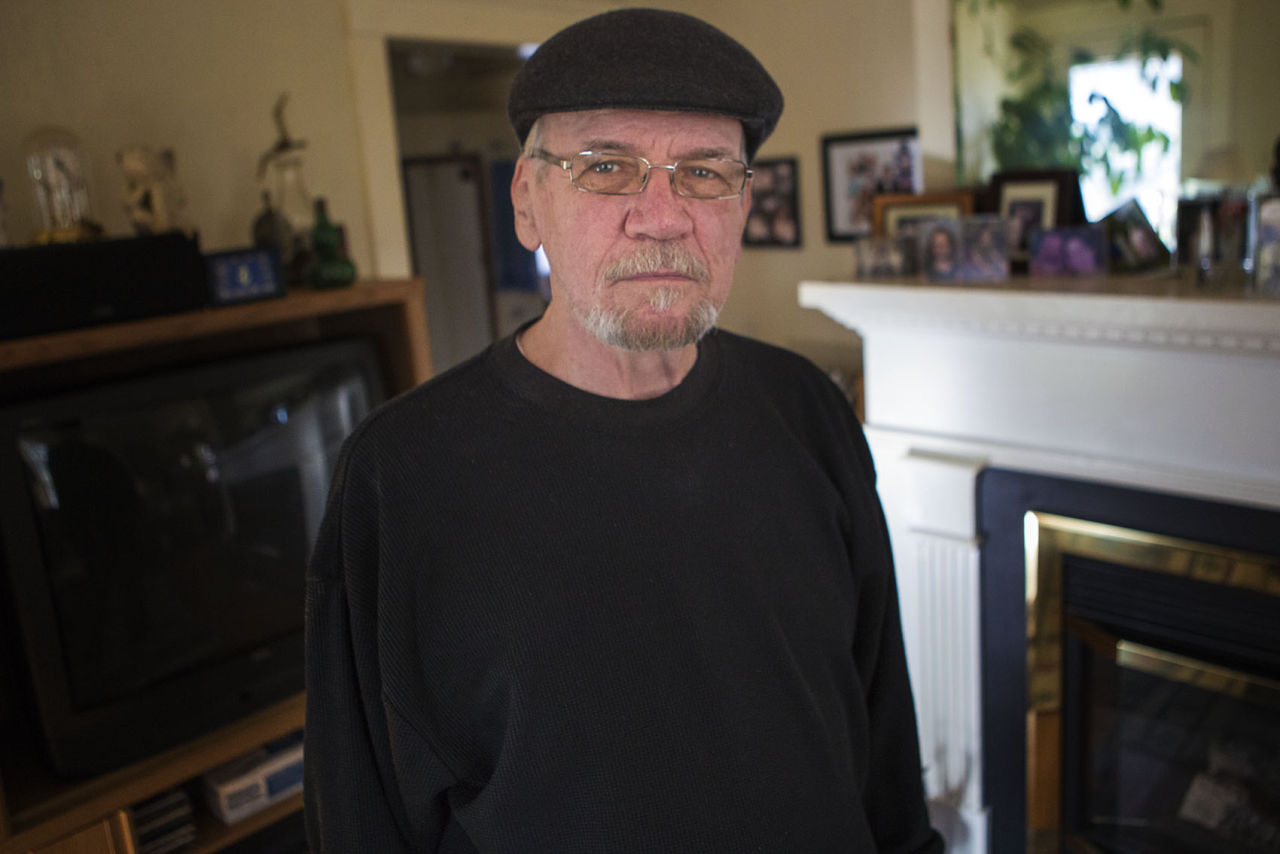

About a legal campaign he never gave up, Cameron said, “I said many times to my attorneys: ‘This is the American justice system. It will work.' ”

And after the 14 years he spent behind bars, and thanks to attorneys and a new DNA test, it did work -- up to a point. Now he's trying to make up for its failure by writing a book and suing the office that prosecuted him.

Correction: Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this post referenced Bristol County, not Berkshire County. We regret the error.

This article was originally published on January 06, 2016.

This segment aired on January 6, 2016.