Advertisement

'The Two Dons Are Dead'

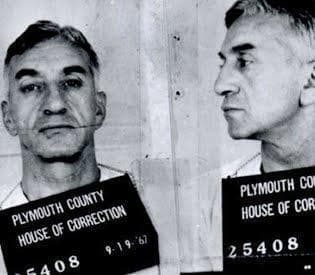

Commentary — Gennaro "Jerry" Angiulo, the former New England Mafia underboss who was the crime king of the North End, died Saturday at age 90.

Running the Mafia family business from Boston to Worcester, Angiulo held court at 98 Prince Street, which became a legendary landmark after FBI bugs recorded him and his brothers and lieutenants talking themselves into a banquet of federal racketeering charges in the early 1980s. Sentenced to 45 years in prison, Mr. Angiulo served 24 years before being released in 2007. He died a free man. WBUR's David Boeri followed his career for four decades and has this remembrance.

They died within a couple days of each other. Two quite different men, in different lines of work, each one persuasive, albeit in different ways. Like other men who cast shadows, they were so big they didn't need two names to be recognized. "Teddy" and "Jerry" were sufficient to command attention.

As we picked up a couple of cappuccinos after attending Gennaro "Jerry" Angiulo's wake Wednesday night in the North End neighborhood where Ted Kennedy's mother grew up, we met a smiling black-shirted waiter in a long, white apron. "The two dons are dead," he proclaimed.

The same North End that had gone from being an enclave of the Irish to the enclave of the Italian immigrants was once the playing field of the Mafia underboss. "This thing of ours" — La Cosa Nostra — involved Jerry and his brothers and their lieutenants and soldiers and numerous coat-holders.

But he was not the "capo di tutti capi." The cannoli was down in Providence, a guy named Raymond Patriarca who had fewer charms than Jerry, but a lot more muscle.

In the North End, most people saw the harmless side of Jerry. In a community that loved to gamble, he ran the numbers game, where you could play a nickel a day.

People I knew, kids, would run up the streets on errands, carrying paper bags filled with thousands of dollars, from bookie to bookie that would end up with the Angiulos, as innocently as the boy next door would run down to the bakery for some scala bread for nonna or zia Judita.

The bad stuff most people didn't see. And dead bodies generally showed up elsewhere. For most Italian Americans here, it was about playing the daily number before the state decided it was too good a racket to leave to the mob.

What won Jerry and his brothers a lot of sympathy was the suspicion that law enforcement was only going after the "vowel" people in its War On Crime. Indeed J. Edgar Hoover's war on crime was the war against the Mafia. And everyone whose name ended in an a, e, i, o or u felt that to be Italian was to be suspected of being mobbed up. Ask Mario Cuomo.

Let's be clear here. If you picked an all Italian-American all-star team, you wouldn't put Jerry and his brothers on your squad. (At mid-century you might have picked Joe and Dom DiMaggio, Fiorello LaGuardia, Tony Bennett and Perry Como — Frank Sinatra had his mob problems — Gino Capelletti and Rico Petrocelli).

The Angiulos were criminals. But the story, now notorious and never too old to be told again, is what happened in Boston when in order to get the Angiulos and their lieutenants and don-wanna-be's, the FBI and the Justice Department decided to make the ultimate consonant wise guy, James Whitey Bulger, a Junior G-Man. (Happy birthday to the fugitive killer who got tipped off by an FBI agent and escaped 14 years ago.)

The scandalous record shows that Bulger was protected from prosecution, knowingly allowed to get away with violent crimes and enabled to become the Irish Godfather because he was a secret government informant against the Mafia.

Jerry went to prison for life after being bugged talking of all sorts of crimes at "The Dog House," as he called his office. He served much of his term out at the federal prison hospital in Devens. I showed up to visit him a couple times, but he never allowed me an audience. Never responded to any of my letters either.

Each day while dropping my kids off at school close to the prison and its exercise yard, I'd roll down the window and yell, "Hey, Jerry." My daughters hated it. "He was a very private person," his widow told me Wednesday night. She thanked me for coming to the wake.

I would have loved to have talked with Jerry, though last night certainly wasn't the best time.

Say this about Gennaro Angiulo. He had a few principles. He never ratted anyone out, never cried for himself in public, never rolled. As gangsters used to say in the old days and with great admiration, "He kept his pie-hole shut."

He served his country in the South Pacific in World War II so he was entitled to full military honors, as was Teddy, who enlisted in the Army but because of his name never saw combat in Korea. Teddy got a procession that led to the Arlington cemetery. Gerry got a funeral procession that included a Hell's Angels honor guard.

This program aired on September 3, 2009. The audio for this program is not available.