Advertisement

When It's Woman Vs. Man, Sometimes There's An Upset

Resume

Football is for boys and cheerleading is for girls.

Basketballing men have the NBA. Their female counterparts have the WNBA, although NBA Commissioner David Stern opined recently that a woman might eventually play for a team in his league. Still, though both men and women engage in boxing, they don’t face each other in the ring.

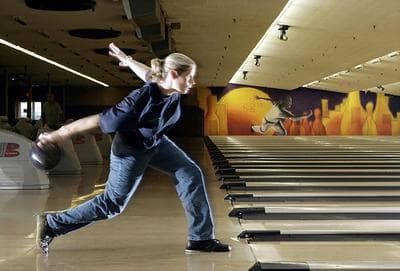

We are accustomed to thinking of most of our sports in terms of separation by gender. But every once in a while, that assumption gets dramatically challenged, such as it did on Jan. 24, when bowler Kelly Kulick beat male bowler Chris Barnes, by 70 pins, to win the Professional Bowlers Association’s Tournament of Champions.

Kulick was the only female competing in the event, but in the wake of her triumph, which was a first for a woman on the male circuit, she did not seem inclined to jump leagues.

“Truthfully, I don’t want to bowl against Chris Barnes every week. If we go for 10 matches, he’s probably going to win nine or 10. I just beat him the first time,” Kulick said. “I think we’re just pushed in that direction because of the lack of availability of events for women. So I think we’re going to see (more women) competing in the male-dominated events, only if there isn’t a ladies’ tour or ladies’ series that they could compete in.”

If Kelly Kulick’s shellacking of Chris Barnes is the most dramatic recent example of a female athlete successfully competing against men (ESPN’s Rick Reilly referred to it as the equivalent of “Man Gives Birth”), it does not stand alone on our sports landscape.

In 2008, Danica Patrick became the first woman to win a closed-course auto race, and last year she posted five top-five and 10 top-10 finishes in the Indy Racing League. She also finished third at the Indianapolis 500. Her recent attempt to move over to NASCAR racing has provoked both praise and, perhaps predictably, ridicule from male drivers.

Driving fast and turning left is not the only sport in which testosterone does not necessarily provide an advantage. Horses, like race cars, don’t care whether the driver is male or female. Though according to Joanie Morris, a former equestrian competitor who is now the high performance communications director for the U.S. Equestrian Federation, some are perhaps more suited to riders of a particular gender.

“Maybe the horse is a sensitive horse that really suits a very quiet, subtle ride from a woman. Or maybe it’s a horse that’s a little bit strong and is better suited to a man and those horses tend to find the right people along the way. And we’re a sport where everyone really helps each other. So it’s a great sort of team community kind of feeling throughout the entire sport.”

“When she finished the whole thing, she said, ‘I need to go back where I belong.’"

U.S. men and women have been equestrian teammates in the Summer Olympics for more than 50 years. And that’s not a concept that’s entirely alien to female Olympians, like Angela Ruggiero, who compete in sports where strength and size matter a lot. A stalwart of the U.S. Women’s Ice Hockey team for more than a decade, Ruggiero also played a game at defense for the otherwise all-male Tulsa Oilers in the Central Hockey League and she regularly trains with men.

“I think all the most elite women have been able to cross-train with men, and just like any other situation when you can put yourself up against the best players, you’re bound to improve,” said Ruggiero, who earned a silver medal in Vancouver.

“In the summertime, I’ve actually relied on my brother. I skate with him quite frequently, and this past summer I actually trained with a bunch of NHL guys. It’s not that you only want to train with guys. It’s that they give you a little extra incentive.”

The concept of the most accomplished female hockey players training with the most accomplished males no doubt delights Laura Pappano, the co-author of "Playing With The Boys: Why Separate Is Not Equal In Sports." Pappano says she gets frustrated when even the best female athletes have balked at challenging the men who play the same game.

“I have interviewed a lot of women athletes who have completed stunningly well, and you’ll remember Anika Sorenstam back in the (PGA Tour’s Bank of America Colonial tournament) in 2003, that first day she was phenomenal,” Pappano said.

“Yet when she finished the whole thing, she said, ‘I need to go back where I belong.’ I think there is a huge piece of social conditioning in which women are utterly nervous, afraid, feel like they’re crossing a line when they compete with men. I think the message has been so powerful that I don’t think we’re getting a fair hearing on this.”

Perhaps so, though golfer Anika Sorenstam isn’t the only superb female athlete who’s ultimately chosen to compete primarily against others of her gender. Even Angela Ruggiero assumes that there will continue to be limits to co-ed hockey.

“I certainly play along side the guys, and I can hang with them, but I’m limited by my size. I’m 5-foot-9, about 185,” said Ruggiero. “When you get to the NHL level, the average size is probably 6-foot-1, 6-foot-2, 210, 215, so, unfortunately, I don’t think it’s going to happen in my lifetime.”

Ruggiero does point out that female goalies have performed brilliantly at various levels of men’s hockey, and that there’s no reason why one shouldn’t make the NHL some day.

Ironically, women who’ve expressed no particular interest in competing against men continue to be prevented from showing their stuff in another of the most popular sports in the Winter Olympics. There is no female ski jumping at the Games, and according to Ann Killion, a contributing columnist for SI.com, its absence has crippled the sport’s development.

“Not having it be an Olympic sport is obviously detrimental to participation numbers,” Killion said. “If you opened it up and you had that kind of platform of the Olympics, which we all just witnessed how exciting, and how much the stuff of dreams that is, then all of a sudden your participation numbers would be completely different.”

The numbers are critical, since the members of the International Olympic Committee have denied female ski jumpers access to the Games because, say the lords, there aren’t enough of them in enough countries to insure a competitive field. But as Dick Pound, a member of the International Olympic Committee for more than two decades, recently indicated in an MSNBC.com documentary, that’s not the only reason female ski jumpers haven’t made the cut. The IOC doesn’t like being told what to do.

“The IOC in a very predictable human reaction might say, ‘Oh, yeah, I remember them. They’re the ones that embarrassed us and caused us a lot of trouble in Vancouver. Maybe they should wait another four years, or eight years, or whatever,’” Pound said, a former Olympic swimmer for Canada.

Pound’s comments suggest that even now, female athletes trying to break barriers not only have to be talented, committed, and fearless, they also have to be politically savvy and persuasive at arguing their case.

The ski jumpers aren’t the only female athletes to find themselves in that position. In the Vancouver Games, the women’s hockey teams from the U.S. and Canada so dramatically dominated the teams from the other nations that after the games, IOC President Jaques Rogge announced that perhaps the sport to which Angela Ruggiero has been devoting herself for most of the past two decades should be dropped from the Olympics because it isn’t sufficiently competitive, which must sound to the women playing for Canada and the U.S. as if they could be penalized, for being too good.

This program aired on March 5, 2010.