Advertisement

After 66 Years, A Mass. Soldier Is Finally Laid To Rest

Resume

Barbara Lowe, of Brewster, and her siblings grew up hearing the legend of their great-uncle.

"I know that Uncle Dick was a rear gunner and he was shot down," Lowe said. "And he was Mom's favorite uncle, and she talked about him all the time."

And, for decades, that's all the family knew. The young man grew up in Carver, went off to war and never returned, dying before Lowe and her sisters and brothers were even born. Lowe's mother, Jean Cole Lowe, went to her own grave without knowing exactly what happened to her favorite uncle.

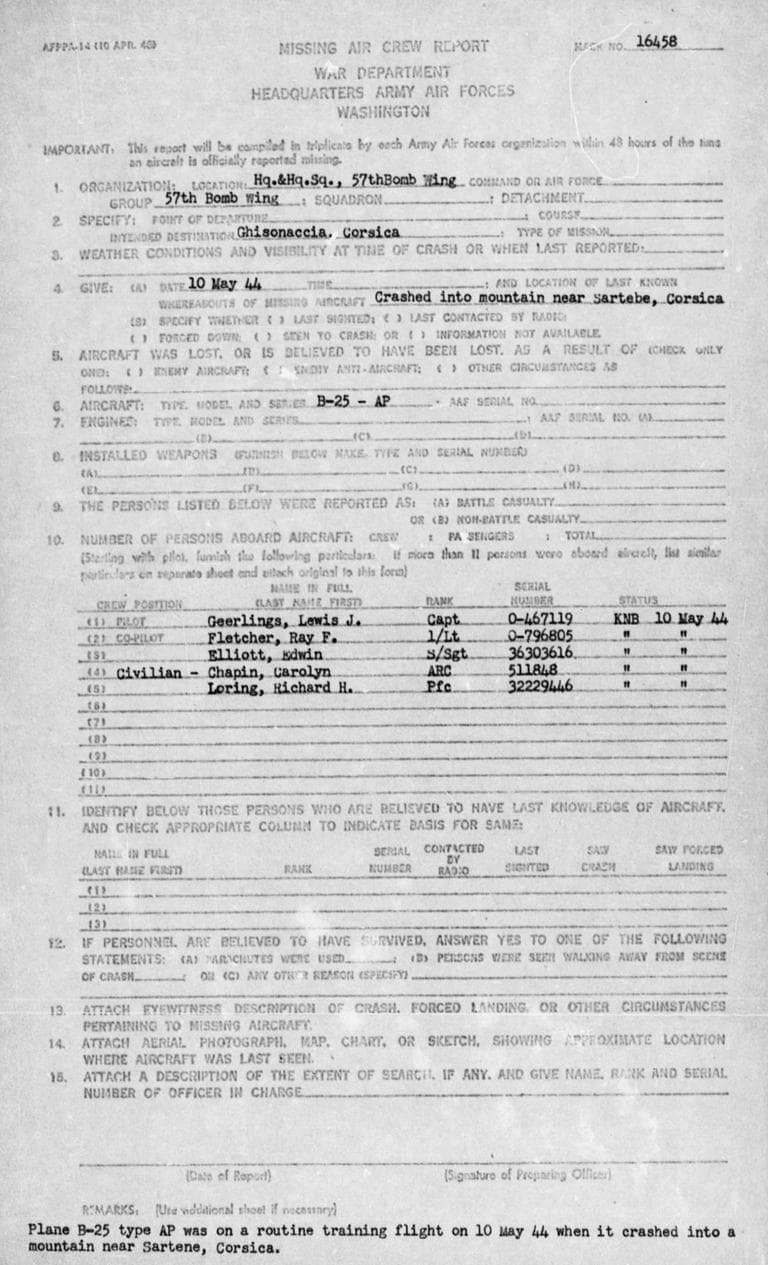

Until five years ago, Richard Loring and four others who were on board a B-25 Mitchell nicknamed "Deathwind" were still listed as missing in action on the southern tip of the island of Corsica.

The Briefing

For more than two hours in early April, retired Air Force Maj. Michael Mee explained to Lowe and two of her brothers the details of the crash that killed their great uncle less than a month before the D-Day Invasion. Mee is an identification specialist with the Army's Casualty and Mortuary Affairs Operations Center. He's briefed dozens of families of servicemen who were killed in past conflicts.

"It's an honor and privilege to bring this information to you," Mee said as he and Capt. Andrew Parris sat around Lowe's kitchen table for the official briefing on their great uncle's death.

"These guys were heroes," Mee said. "These were America's sons and daughters who went overseas to deploy, and went into harm's way, and some didn't come home."

And for more than 60 years, Richard Loring was one of those heroes who didn't come home.

Loring wasn't assigned to the crew of the B-25, which was flying what was to be a routine supply mission from one side of Corsica to the other. He may have just been hitching a ride, like fellow passenger Carolyn Chapin. Chapin was a correspondent for the American Red Cross, writing articles that brought the Red Cross's front-line humanitarian efforts back to America.

And while family legend may have been that Loring's plane was shot down, declassified documents showed soupy weather was to blame.

"They actually hit the side of a mountain that was about 4,000 feet in elevation," Mee told the family.

"(An eyewitness) heard the airplane overhead, saw it fly into the cloud bank, and he heard an explosion, he heard a crash," Mee added. "So, whether or not they misjudged the altitude, they had navigational error, (it's) not quite clear because there were no black boxes back then. You really can't tell. But weather was a primary role in the crash."

The plane crashed amid huge boulders on a remote part of Mount Cagna on the island off the coast of France. The five on board probably died instantly as the plane was consumed by fire.

A few days after the crash, local farmers, along with some Corsican gendarmes, made a trek to the crash site and discovered the twisted wreckage, but no human remains were found.

Mee said that over the intervening years there were conflicting reports.

"A team goes up there and says nothing survived that crash, no human remains," Mee said. "Then you come back later on and teams did find human remains."

Some locals said they found bones near the wreckage and that they placed the bones in the crevices between the boulders. There was also an unconfirmed report that some villagers buried some remains on another part of the island. Official expeditions were launched but nothing was ever found, and the reports remained unsubstantiated.

That is until 1988, when gendarmes discovered bone fragments at the site and notified the U.S. Embassy in Paris.

But for some unknown reason, the case sat until early 2005, when after four trips to the crash site two French civilians reported that they found more human remains.

A Search Anew

Armed with this new information, the Pentagon dispatched a team from the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command, or JPAC, to search for the remains of the missing Americans.

"I think if you ask everyone here at JPAC they will tell you it's rewarding on a whole new level," said Maj. Ramon Osorio, JPAC's public affairs officer based at Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii. "It's rewarding to be part of such an effort.

"We have several skilled technicians ranging from scientific experts, military operations, planners, civilians, people from all skill sets, all trades, uniquely putting all that talent together into one effort, merging in unison to that one effort and that noble cause of establishing that type of accountability over our service members who have gone missing from past conflicts," Osorio said.

The JPAC team spent five days at the crash site. Team members scoured the crevices looking for bones and any other personal items that may have survived the crash.

JPAC anthropologist Dr. Matthew Rhode didn't go on this mission, but is familiar with the case.

"The focus of JPAC is to recover remains," Rhode said. "And be that as small as a tooth crown, or small bone fragment, that is what we're trying to do. And the fact that they saw bone the first day, they'd go, 'Hey, we're doing it. We're getting this thing done.'

"And they would have been very motivated to come back every day to continue and move along to make progress on the site," Rhode added.

With the bones and other remains recovered, the next job was to identify them. And, like an episode of "CSI," DNA samples were used to sort out the remains.

Returning Home

Back in Loring's hometown of Carver, traffic moved along Route 58. Drivers appeared unaware of the granite monument bearing the names of those from town who served in World Wars I and II. Loring's name is etched on that monument with a star to indicate he died in the war.

That's pretty much the only connection left to the town where he grew up. Nearly all of his contemporaries have since passed away, including his sister, and the niece who idolized him.

Carver Town Administrator Richard LaFond says the town is not too sure how to feel about Loring's return.

"On one hand, you're glad you can be a part of history and honoring this person's service," LaFond said. "On the other hand, this is a resident of the town who is in many ways a distant memory."

On Friday, a handful of town officials and local veterans stood at attention as a military honor guard carried Loring's casket from a hearse into the local funeral home (Raw Video). The procession from Logan Airport to Carver was escorted by State Police trooper Doug Loring, who recently discovered he is a distant cousin of Richard Loring.

Carver will bring out its Fourth of July bunting for Monday's funeral.

And after a memorial service at the United Parish Church where he once worshiped, Loring will be buried in the family plot next to his mother, sister and niece. Barbara Lowe said that would please her mother.

"She'd be very happy," Lowe said. "That's why, as soon as I knew, I said, 'He has to be buried next to Mom.' I know she'd be real happy."

This program aired on May 10, 2010.