Advertisement

Health Quality Innovators Talk Costs

The child of Chinese immigrants who is transforming care for the elderly, a man inspired by the death of his brother, and a woman whose leadership is described as a mix of acid and whipped cream, are among those honored this year by the New England Healthcare Institute.

The awards showcase the work of these five men and women on improved patient care. We asked the honored health care innovators how what they’ve learned about improving care might translate to controlling health care costs.

Let’s begin with the petite hospital executive who blends acid and whipped cream in running Denver Health, a national model in health care for the uninsured.

Patricia Gabow

Denver Health CEO Patricia Gabow looks to leaders in other industries like Fed Ex, Ritz Carlton and Toyota. Gabow then adapts their approach to her goal: improving patient care.

Using Toyota’s LEAN model to analyze more than 300 procedures at Denver Health, Gabow says she found that about 60 percent of what has happening was waste.

"By taking out waste you improve quality and lower costs and make it (health care) more patient friendly," says Gabow. "Who wants to sit in a waiting room or get a test you didn’t need? But unfortunately, in health care, a lot of what we think is waste is someone’s else’s income and that’s why it’s very difficult to change this system."

Gabow says Denver Health is $66 million better off in savings and efficiencies since adopting the Toyota model. Now Gabow says she, like some hospitals in Massachusetts, is ready to test new ways of getting paid for health care. She expects to try global payments, where doctors and hospitals work under a budget for patients instead of getting paid for each office visit, test and procedure — what’s known as fee for service.

"You have to get rid of fee for service if you want to improve value and lower cost" says Gabow. "It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to say, if you pay people for doing more that they’re going to do more. This is human behavior."

Jennie Chin Hansen

The problem of paying for every test and procedure without anyone coordinating that care or deciding if it's worthwhile is especially glaring among the elderly, says Jennie Chin Hansen, CEO at the American Geriatrics Society.

"Sometimes you get a frail older person, they’re kind of like a walking bar code," Hansen laughs in exasperation. "They go by and someone goes zip, zip and a bill goes to Medicare, and Medicare pays."

Hansen is the child of Chinese immigrants we mentioned in the introduction. Her pioneering efforts to keep frail elders in their homes by bringing services to them started 26 years ago when she moved her father out of a nursing home.

Hansen proved home care is both more desirable and cheaper for most elders. She funded rides, therapists, home health aides and medical services through a global payment. But Hansen says moving from a system where everything in health care triggers a separate bill, to global payments where doctors join efforts around a patient and manage a budget is a fundamental change.

"If people aren’t thoughtful about it on the front end, when some untoward issues develop later on, there’s such a pushback, politically, that you can’t go further" Hansen said.

Caroline Clancy

Not all the New England Healthcare Institute honorees are ready to talk about how to rein in health care spending. Dr. Caroline Clancy, who directs the national Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, is known for developing tools to improve patient safety and creating multi-lingual health care consumer guides.

Clancy says that while patients and doctors have a lot of choices in treatment, they don’t have enough proof yet about which treatment works for which patient.

"Filling those information gaps has got to be our first crucial step before we can talk about how do we get to better value in health care," Clancy said.

There is at least one common theme among these national leaders about what needs to change in health care: the doctor-patient relationship.

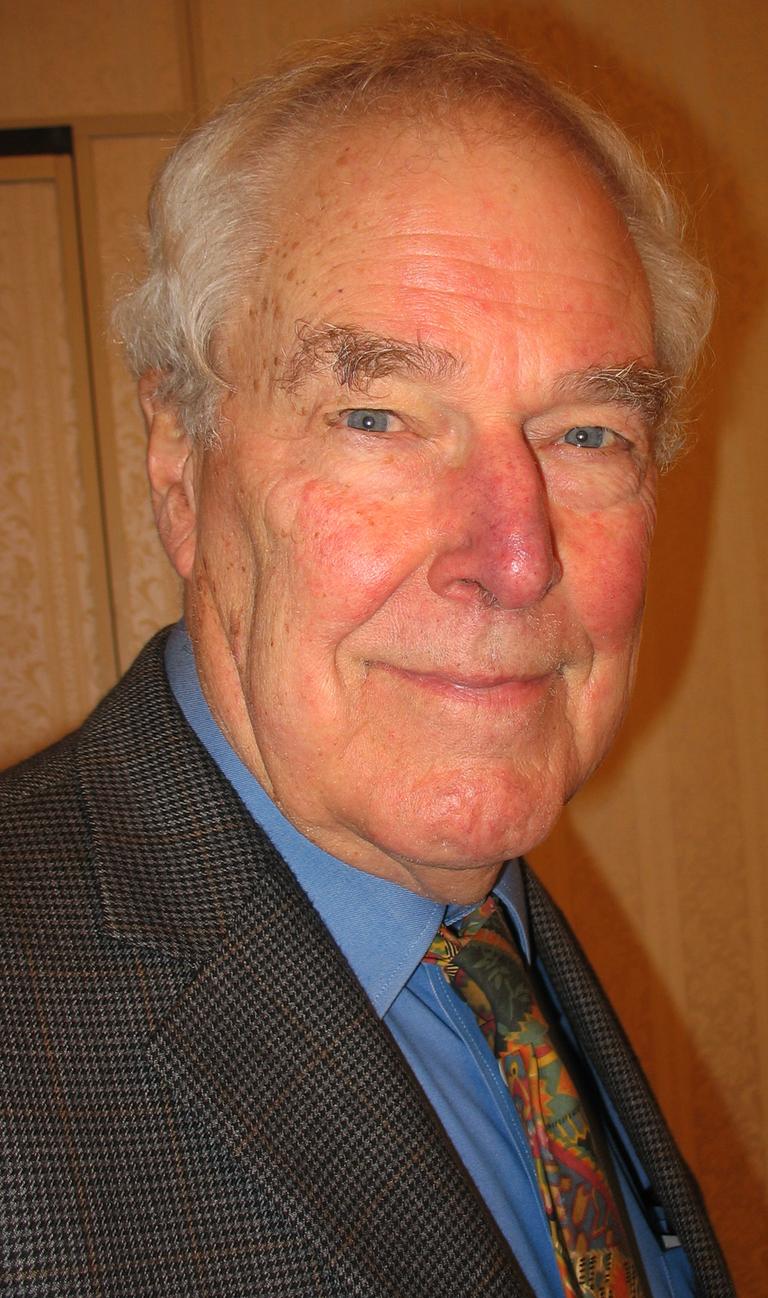

Jack Wennberg

"Traditionally patients have pretty much relied on the physician to make the diagnosis and decide on the treatment," said Dr. Jack Wennberg, who founded the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy.

Wennberg says leaving all the power with the doctor might be OK if there were no choices to make about our care, but in many cases there are.

"For example," Wennberg said, "whether you would have a knee replacement or some other way to manage your arthritis. Or if you have cancer of the breast, whether you would like a lumpectomy or a mastectomy. Those are very personal decisions that need a personal approach. That’s what we mean by shared decision-making: this whole strategy of involving the patient actively in the decision-making process."

Wennberg is frequently honored for research that shows how much the price, quality and use of health care varies from city to city and region to region. Wennberg says this broad variation is another reason patients need to ask a lot of questions and make their own decisions.

Another honoree, Jamie Heywood, agrees with Wennberg but says it will be difficult to change the doctor-patient relationship because doctors aren't used to engaging with patients, questioning their own decisions, or questioning each other.

"It’s the questioning of whether you are right that produces improvements in quality, and that is something that doctors are actually trained not to do," says Heywood.

Heywood, whose brother died of ALS, co-founded the website, PatientsLikeMe.com that is helping patients take charge of their care by sharing knowledge and insight. He questions why there is so much emphasis on reducing costs as opposed to making health care better.

"It's about value" argues Heywood. "The reality is that so much of what we do now in health care is harmful. I want a system where someone says they’ll do something and they get paid for the value they create. If we have that, then I can't imagine not wanting to spend as much as possible on health care because I want to have a long, happy life."

Heywood argues there is little if any connection now between payment and whether the care we receive works. Some insurers, however, are taking steps in that direction and offering physicians bonuses based on their performance.

This program aired on October 29, 2010. The audio for this program is not available.