Advertisement

William Bulger Faces His Brother's Legacy

Now that alleged mob boss James "Whitey" Bulger is back and behind bars in Massachusetts, troubles seem to be just starting for rest of his family.

As prosecutors and the news media recount Whitey’s alleged crimes, his well-known brother, former Senate President William Bulger, has met with what's been described as reproach and disgrace.

The horde of reporters and photographers and cameramen outside the doors of the federal courthouse were waiting for William Bulger.

Gone for William Bulger is the protective bubble that once insulated him from anyone publicly asking him about his older brother. Now he walked into and out of the courtroom without looking to his right or left and sat wincing and pinching his eyes as he pinched his words in that written "statement" he had released.

He had expressed sympathy "to all the families hurt by the calamitous circumstances of this case." It was as close to candid as William Bulger ever came to the fact his brother is charged with murdering 19 men and women in a long, reign of terror.

What's unusual is that this man who climbed so high he could command the loyalty of college presidents, elected officials, judges and the city's business and cultural elites has lost so much standing. Even his lecture to a group of senior citizens in Marshfield last week on James Michael Curley prompted a call for police presence just in case Bulger was targeted by angry relatives of his brother's alleged murder victims.

William Bulger told a congressional committee in June 2003 that his brother “marched to his own drummer and traveled a path very different from mine.”

But the need to explain his relationship to his brother never pressed on Bulger during the 17 years he was Senate president. Both the fear of his well-documented retribution and the loss of access had cowed the State House press corps and politicians from ever asking.

Such was the relative insulation from his brother Whitey that William Bulger in the 1990s could even joke about his notorious brother having questionably shared a winning lottery ticket.

Advertisement

Just six years earlier, in 1986, the president's Commission on Organized Crime had identified Whitey Bulger as "a reputed killer, bank robber and drug trafficker."

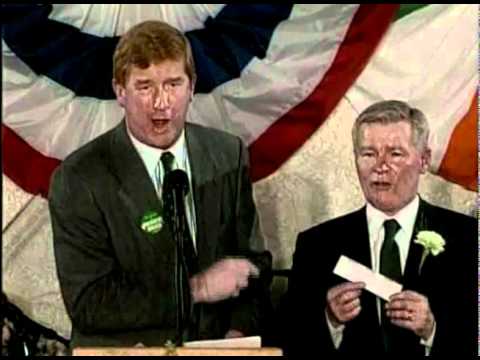

Even after Whitey Bulger became a fugitive from federal charges in 1995, William Bulger's St. Patrick's Day follies would include Gov. Bill Weld singing to the tune of “Charlie on the MTA”: "will he ever return, no he'll never return."

Five years later, in 2000, Whitey still hadn’t turned up, but the skeletal remains of six murder victims did. Bulger’s criminal associates said Whitey had strangled them or blown their brains out.

Suddenly the myth of the Robin Hood who’d handed out turkeys and helped nuns cross the streets of South Boston was hollow. Court hearings had discovered Whitey had also been a protected FBI informant, a snitch in a culture with a longstanding hatred for those who informed against the Irish.

Now a congressional committee headed by Indiana Republican Dan Burton was beginning to bore in.

William Bulger and his family turned back the FBI when it sought help in finding or calling upon Whitey to turn himself in. Bulger even took a hidden phone call at a prearranged location to avoid detection.

And his brother John helped manufacture fake IDs for Whitey and even lied to a grand jury about a safe deposit box they shared. For that John, better known as Jackie, became the first Bulger to go to prison in 50 years. Even their sister Jean got into the act, battling the state to collect her fugitive brother’s lottery earnings upon William Bulger’s counsel.

In December 2002, the university president and former State president who was used to getting his way was forced to appear before that congressional committee in Boston. After the committee rejected William Bulger’s request to testify in private, he was forced to endure in public the scene he had always hoped to avoid.

Taking the Fifth Amendment was President Bulger’s right. But once again he had chosen loyalty to his brother over the interests of justice and public safety.

Committee Chairman Dan Burton compared Bulger unfavorably to the brother of the Unabomber, who was charged with killing fewer people than Whitey was. The Unabomber’s brother had turned him.

As to Whitey, William Bulger told a secret grand jury in 2001: “It’s my hope that I’m never helpful to anyone against him,” that according to transcripts, which were leaked to the press in 2002.

By the summer of 2003, William Bulger had been subpoenaed again, this time to Washington, and this time with immunity so he could not refuse. But Gov. Mitt Romney and Attorney General Tom Reilly were already calling for him to step down from his position as UMass president.

His answers to questions before Congress that June would lead to his ouster. Despite denying any knowledge of his brother’s criminal activities, William Bulger and Whitey’s alleged criminal associate Steven Flemmi were next door neighbor, living no more than 50 feet away. Whitey, William and Flemmi dined together regularly according to a government witness.

Bulger’s professed lack of memory, curiosity and knowledge of what had reported in the news for years was simply stunning. It was “selective memory loss,” charged one congressman. When asked what business he thought his brother was involved in, Bulger had answered “things that were extra-legal.”

Within a month and a half, he was forced out as university president. He got severance of $1 million and walked off with a state pension of $200,000 a year. His lawyer called William Bulger a victim.

Now that Whitey is back, all this and still more questions confront William Bulger and his greatly diminished reputation. For him as he recently referred to his own brother, these are “calamitous circumstances” indeed.

This program aired on July 22, 2011.