Advertisement

Cambridge Firm Launches First-Of-Its-Kind Spinal Cord Injury Study

ResumeFor many people with spinal cord injuries, the word "cure" is one they hesitate to say. Some follow spinal cord injury research closely; others choose not to.

But one FDA-approved study upcoming from a Cambridge firm is attracting a lot of attention because it marks a major milestone in spinal cord injury research.

'Scaffold' Study

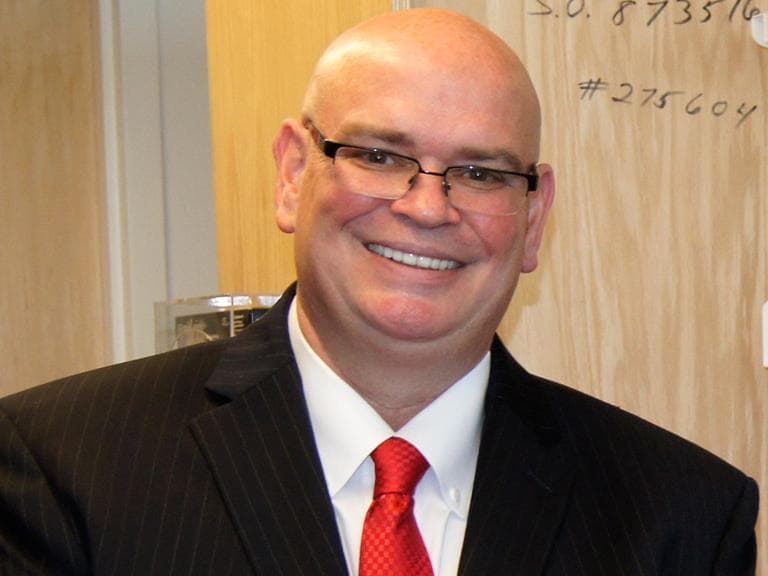

Four floors up at One Kendall Square here in Cambridge, in the labs and machine-shop-like rooms of InVivo Therapeutics Corp., CEO Frank Reynolds hopes to shake up the world of spinal cord injury research.

"This is our chemistry lab," he said while giving me a tour. "So all of our chemical engineering is done here. Our hydrogels and scaffolds are all made right in here. So we invent, discover and make right here."

One of the products InVivo makes is a tiny, sponge-like device called a “scaffold.” The company has received FDA approval for a safety study of the scaffold. The study will be small scale — just five patients. But it's a big deal for another reason. It will be the first time a device to treat spinal cord injury will be studied in humans.

The study subjects will undergo surgery to have the scaffold inserted directly into their spinal cords. The biodegradable scaffold is meant to do its work in six weeks and then dissolve.

"If you visually picture a cigarette filter, you know, cigarette filters are very light," Reynolds explained. "They're a little airy. It's shaped like that, because the spinal cord is round. It's a cylinder."

More on the scaffold in a minute. But first, a look at the deep — and sometimes mixed — emotions surrounding the research.

'Incremental Improvements' Sought

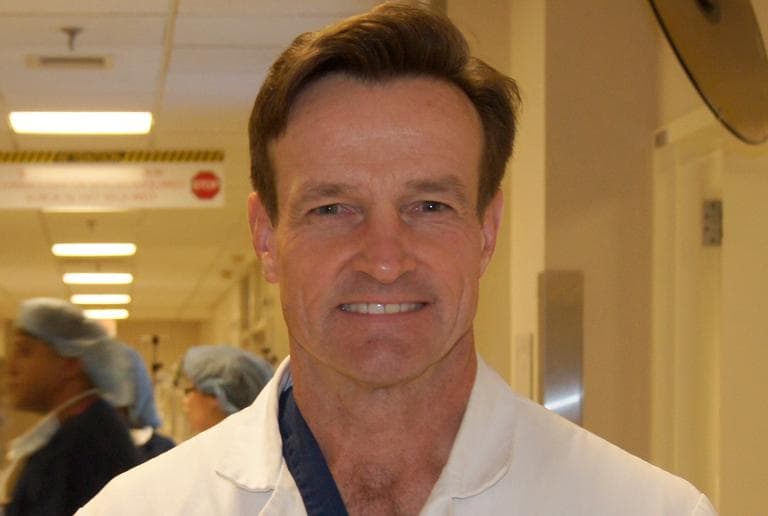

Dr. Eric Woodard, InVivo's chief medical officer, will perform the delicate spinal cord surgeries on the study subjects.

"There's excitement, but at the same time an equal amount of caution," Woodard said. "We want to do this right. There's a tremendous amount of concern for safety. If you've lost so much function, obviously there's an enormous importance attached to maintaining what you've got left and not creating more of a problem due to the treatment itself."

Woodard, who is also the chief of neurosurgery at New England Baptist Hospital in Boston, is very careful to not raise the hopes of people with complete spinal cord injury — which means they have a total absence of function below the level of the wound. For example, Woodard does not talk of people walking again. And he does not utter the word "cure."

"'Cure' is certainly not a scientific term; it's an emotional term," he said. "And the enormous complexity of spinal cord injury really requires that any use of the word 'cure' has to be used in a very careful manner. We're looking to make small, incremental improvements."

Incremental improvements like restoring someone's grip, or tricep function, so the person can support himself or herself on their elbows and transfer in and out of a wheelchair.

"Even very small improvements in neurologic function can be very, very significant to people's lives," Woodard said.

The study will involve patients who've been paralyzed for just a matter of days, or a couple of weeks.

Woodard will implant the scaffold directly into the wound in the spinal cord, the goal being to stop the injury in its tracks and stabilize the area. Without treatment, the spinal tissue gets progressively more inflamed for about three weeks after injury, causing further damage.

"The whole idea is to get in there and provide something for the cells that haven't scarred yet, that haven't received that signal yet, and give those cells something to cling onto," Reynolds said. "And then by giving that tissue something to grab onto, it can survive and thrive."

And that might mean maintaining, or regaining, function.

InVivo's History, And The First Human Tests

Reynolds' motivation stems from personal experience. He was paralyzed for eight days in 1992 as a result of accidental nerve damage during spinal surgery.

"I ended up living in my parents' living room in a medical bed for about five months," he said, "and went through the typical, you could say, horror that people go through."

He says it took six years of extensive physical therapy and living in a body brace for him to recover.

Several years later, he happened to meet MIT chemical engineer Bob Langer, who had decades earlier developed a polymer material as a support in tissue engineering. Researchers had studied the use of that material in rodent spinal cords. Further collaboration led to the founding of InVivo Therapeutics, which has refined the technology.

The company's scientists have seen widespread success with the spinal cord scaffold in monkeys paralyzed in the lab, and they hope that will translate to humans.

"In my opinion, it's like Neil Armstrong's first step on the Moon for neuroscience, you know?" Reynolds said. "We're getting in there, we're getting our first swing."

Dr. Woodard points out that lab monkeys don't have the same kind of contusion in their spinal cords as the human study subjects, who will have suffered from things like crashes and shootings. That's because of humane considerations for the animals and the need to create an injury that can be replicated.

But if researchers are successful in their early studies of the device, their goal is to one day implant the scaffold carrying medications and stem cells — possibly sparking regeneration in the spinal cords of people who've been paralyzed for some time.

Watching, But Not 'Waiting For A Cure'

People like David Estrada, of West Roxbury.

"Will I ever run again or regain what's, you know, 'normal function'? I don't know," he said.

Estrada says either way, he'll be fine. He's adjusted to life as a paraplegic in the 18 years since the motorcycle accident that paralyzed him.

But three days a week, he comes to Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital here in Cambridge, straps himself into a rowing machine, and sticks electrodes to his legs to get them powering the machine.

"And so I'm literally pressing a button to contract my quadriceps to row out and pull on the rowing handle," Estrada explained, "and then I release the button to come back in, and it contracts my hamstrings."

Estrada says he does the exercise to improve his circulation and help prevent bone fractures. But it's also to build muscle and bone strength in his previously atrophied legs because of the possibility he might one day benefit from new spinal cord therapies — like the ones InVivo is developing.

"If it happens, it's great," he said. "If it doesn't happen, I'm not going to be completely depressed."

Estrada says he has a good quality of life. But he will be following InVivo's studies closely.

"It's great that the research is there," he said. "I am very proactive and advocate for a cure. But myself personally, and this is what I tell other patients is, live day to day. You can't rest your laurels on just sitting around and waiting for a cure."

InVivo is working to identify hospitals in Boston and central Pennsylvania that will conduct the research with them. They're also setting up a system to identify new spinal cord injury patients to enroll in this first-of-its kind study.

This program aired on May 21, 2013.