Advertisement

J. D. Salinger — The Writer's Life Is Not A Cinematic Life

“The [expletive] movies. They can ruin you.” That’s the defiant Holden Caulfield in J.D. Salinger’s “The Catcher in the Rye,” the 1951 novel that put American youth culture on the literary map and skyrocketed Salinger to fame. It also, arguably, sent Salinger into a self-made writing bunker for the rest of his days.

Just after “Catcher” came out, Salinger retreated to Cornish, N.H. and lived there until his death in 2010 at 91. For the most part he kept to himself, declining interview requests, shielding his life from photographers and desperate fans, and to the disappointment of a legion of readers, not publishing after 1965.

Whether or not Salinger was writing over the last half-century is of central concern to “Salinger,” the documentary about the author’s life, which opens at the Kendall Square Cinema Friday Sept. 20 so word is out: Yes, he was writing. And, the film has problems.

With a companion book released earlier this month by “Salinger” director Shane Salerno and writer David Shields, along with subsequent criticism of Salinger’s controversial relationships with teenagers, the long-guarded hive has been poked.

Can a movie, or its buzz, ruin a man? More to the point: should you bother seeing this one?

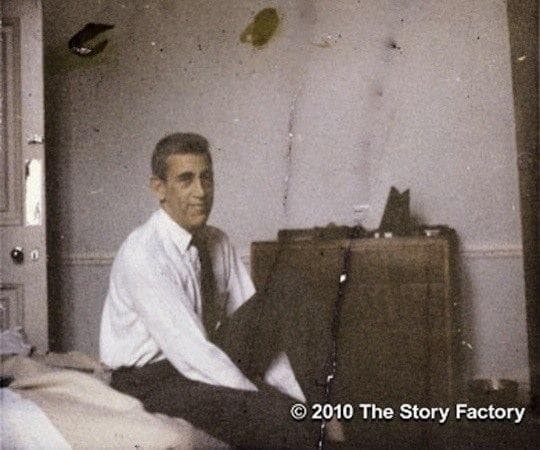

First, it’s a documentary about a writer, an already visually arrested subject, which is why so few succeed. “Salinger’s” footage is composed of the expected talking head interviews and camera zooms on archival photographs, many of which this film makes public for the first time. The more rare the photo, such as the only known snapshot of Salinger writing “Catcher” during his WWII service, the more frequently it reappears. There’s also dicey dramatization. One thread has a Salinger character on a stage, hunched over a typewriter while scenes from his interior are projected on a movie screen behind him. Take that with a bombastic, often militant score, and it’s easy to imagine Caulfield launching a Coke at the whole phony enterprise.

Second, it’s an artist biopic, a knotty genre made more so in this case by the fact that the main subject is held up by many as the modern embodiment that art should speak for itself, without any biographical interpretation and certainly without any cinematic adornment.

Salinger painstakingly held on to—as one example—“Catcher’s” movie rights to prevent Caulfield from ever appearing in the “expletive” movies. The knot thickens when critics such as Ron Rosenbaum point out the danger of the simplistic equation of Caulfield as Salinger’s alter ego, a notion this film cultivates.

Because privacy is anathema to our tell-all culture, there could be lessons learned from the author’s reticence. But “Salinger” goes wide instead of deep. There’s a connection drawn between “Catcher” and three infamous murders and news that in his later years he ascribed to Vedanta philosophy. Actors are waltzed in for no apparent reason, other than for their celebrity.

A major portion of the film plods through the formation of Salinger’s psychological thicket before, during, and just after WWII, including a mental breakdown. His initial rejections from the New Yorker (between 1941 and 1946, not a brow-raising wait for most writers) are so overplayed that they come off as a desperate ploy in lieu of actual tragedy. The unintentional consequence is that this section makes sensitive terrain—the horrors of war and the now-known realities of PTSD—laughable.

Salinger did not lead a laughable life nor did he write laughable fiction. Jean Miller was 14 and Joyce Maynard was 18 when an adult Salinger initiated relationships (23 years apart) with them. Their interviews shade his demons and bring gravity to the film, though as Maynard has written since its release, it does so “politely.” (She also wrote a memoir of their time together “At Home in the World” and is a native of New Hampshire.)

However pathological Salinger’s off-page behavior, he was, is, a literary tour de force, and yet the film treats his oeuvre and the promise of future publication like the trumpet line in a halftime show. There’s so much more to his work. Talk of his writing in this film is just talk, with neither the grip of Caulfield’s acerbic profanity nor the context of thoughtful literary scholarship. One could leave the theater without knowing much of anything about the Caulfields or the Glasses—the very families that are supposed to rock the literary world when their full sagas are published starting in 2015.

It’s been written that Salinger’s estate has copyright under such lock and key that his work couldn’t be quoted. Still, where there’s an imagination, there’s a way. Two recent documentaries with admittedly more access found enticing ways to weave writers’ lives and their respective work into refreshing biopics. After seeing, “Patience (After Sebald)” and “Plimpton! Starring George Plimpton as Himself” I headed straight to the books.

In the end, what could be most upsetting about “Salinger” is that it does not inspire one to seek out his stories, whether for the first, third, or final time. Maybe the buzz is all there is. And for anyone who loves Salinger's writing, that's the ultimate four-letter insult.

___

On Wednesday, The Weinstein Company announced that the version of "Salinger" opening on Sept. 20 differs from the version released earlier this month and screened for press. According to a statement, it will will feature some cuts, "new, never-before-seen material," and will announce that director Shane Salerno will be developing a feature film adaptation of the documentary.

___

Erin Trahan edits The Independent (www.independent-magazine.org) an online magazine about independent film and is on the masthead at AGNI (www.bu.edu/agni).

This program aired on September 20, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.