Advertisement

Pathologist: Legacy Of A 31-Year-Old Lung Cancer Patient

He was only 31 years old, the autopsy paperwork said.

What could have taken the life of someone just a few years younger than me? Stage 4 lung cancer, the chart said. And Kevin wasn’t a smoker.

I made the first incision. As I worked, it became clear that cancer had overtaken Kevin’s body. Tumor had encased his lungs, growing into the rib cage and heart, blurring the normal anatomical landmarks.

As a pathologist, I have learned that cancer knows no boundaries. It can strike anyone regardless of age, sex, race or class. I’ve also witnessed a disheartening trend over the past few years: many of the patients I see with cancer are younger and younger.

When I began my training, it was eye-opening to diagnose breast cancer in a 40-year-old. Over time, that yardstick has dropped a decade, then more. Once, my colleagues and I would stand in amazement having diagnosed the disease in 30-year-old patients. Now, unfortunately, that bar is set at more like age 20.

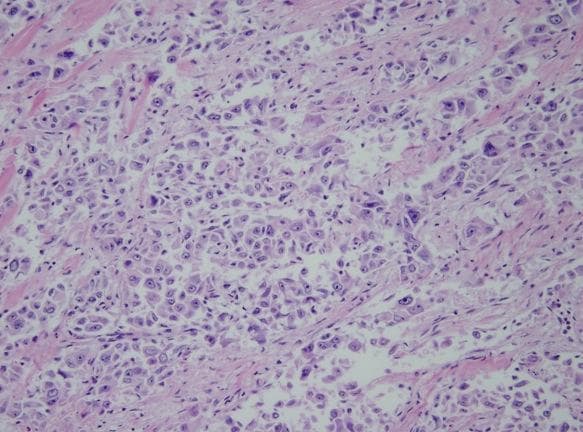

What is cancer? Cancer can be microscopic, only a few cells under my microscope, or it can be large and disfiguring. It can be indolent or aggressive. Some cancers may never cause harm while others will be relentless and deadly. This is something I have yet to understand. Many pathologists and other researchers are working on this exact question.

To me, everyone who battles cancer is a hero. Each patient is unique. It might be tumor characteristics seen on a pathologist’s slide or data collected from a clinical trial, but all patients teach us important lessons. They add to our growing understanding of cancer and search for a cure.

Kevin’s oncologist, Dr. Daniel Costa of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, came over to collect some tumor tissue. It turned out that Kevin was one special patient. His tumor harbored a rare mutation in the ALK gene which made him eligible for the then still-experimental inhibitor PF-02341066. Being one of the first patients treated with the drug, he was a pioneer, blazing a path where no one had been before.

Kevin was also an outspoken advocate for lung cancer, working to erase the stigma that it is a patient’s fault because they smoked.

About 15% of lung cancers occur in patients without a smoking history, many of them young like Kevin. It is in this population that the likelihood of finding a mutation that can be targeted is highest. This is the new world of personalized medicine, and as a pathologist I am looking for these mutations.

Kevin’s tumor initially responded well to the drug, but then developed resistance. He lost his battle just days after his marriage.

His journey helped establish that experimental drug as the standard of care for his particular tumor, leading to FDA approval of the drug, now called crizotinib. I encourage everyone to read Kevin’s story, told best by Dr. Costa in a Journal of Clinical Oncology article: More Than Just an Oncogene Translocation and a Kinase Inhibitor: Kevin’s Story. He writes in part:

“Patient advocates play an increasingly important role in cancer drug development, and I am certain that Kevin’s efforts on behalf of other patients during those short months when he felt well were much more important to lung cancer research than anything I have done in my career to date.”

Kevin’s legacy lives on. He worked tirelessly, urging patients to make sure their tumors got tested for specific mutations, which added to our knowledge of the molecular basis for lung cancer.

We are in the midst of a genomics revolution in which molecular profiling of tumors is becoming more and more commonplace. This era of personalized medicine is changing our perception of cancer.

A paper recently published in Nature Genetics suggests that we treat cancer based on its genetic signature, not its organ of origin. In other words, there will likely be a day when we no longer look at a cancer as a lung, breast or colon cancer, but a tumor with X, Y or Z mutation. The search for and targeting of these actionable mutations in cancer will be the new norm.

What is cancer? It is patients like Kevin that have furthered our understanding. We are closer to this answer than ever before.

What can you do? For information on how you can help, please visit the Lung Cancer Alliance. Note: It’s holding its 5th Annual Shine a Light on Lung Cancer vigil on Nov. 14 at the Prudential Center.

Dr. Michael Misialek is Associate Chair of Pathology at Newton-Wellesley Hospital and Assistant Clinical Professor of Pathology at Tufts University School of Medicine. Don’t miss his previous post on “The Unseen Pathologist: Why You Might Want To Meet Yours.”

This program aired on October 9, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.