Advertisement

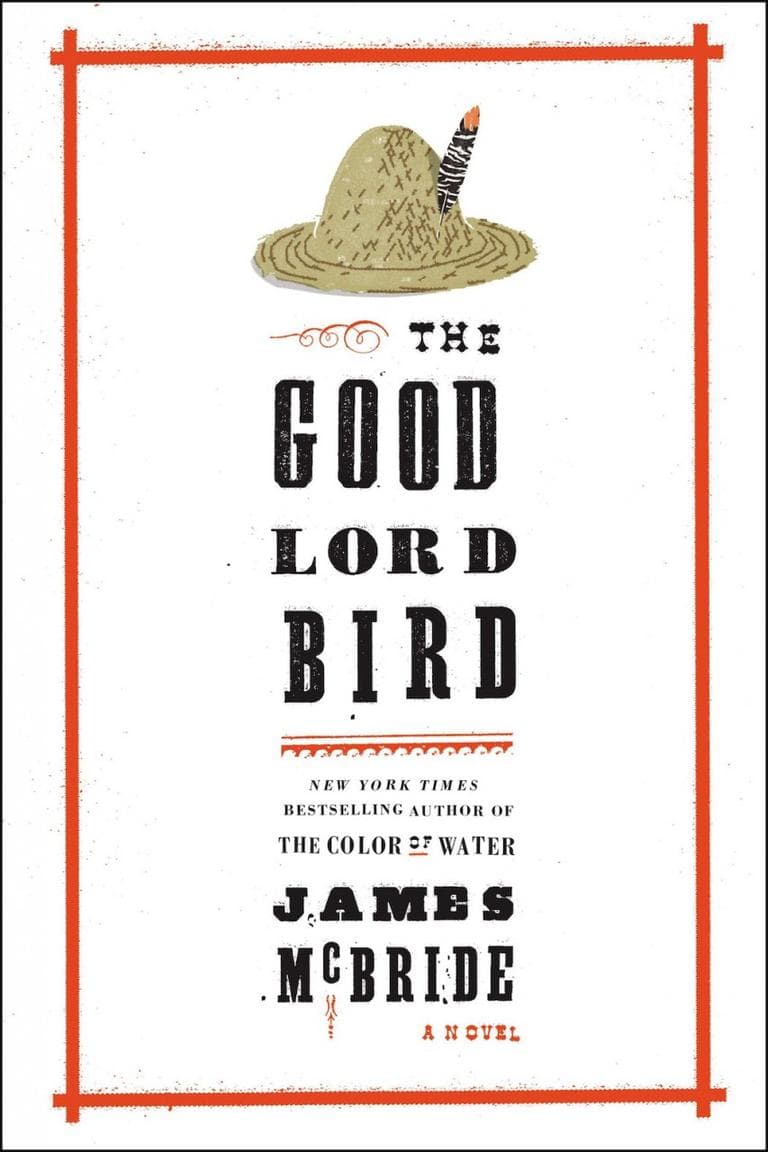

James McBride Takes An Admiring, Humorous Look At John Brown

As James McBride is both an accomplished writer and saxophone player you might expect that his new novel, “The Good Lord Bird” is about his love of Charlie “Bird” Parker rather than a parodistic ride along with abolitionist John Brown.

What isn’t surprising, given McBride’s superb way of putting words together and his hilarious way of telling a serious story is that “The Good Lord Bird” is one of the finalists for this year’s National Book Award in fiction, with the winner to be announced Nov. 20. He’s in pretty decent company. Jhumpa Lahiri. George Saunders. Thomas Pynchon. Rachel Kushner.

I loved the Lahiri and Saunders books, but I’m rooting for McBride and not just because I was even more impressed with his book than with Saunders' and Lahiri's. Back in what feels another lifetime I used to edit McBride’s copy when we were working in the Globe’s Living-Arts section in the ‘80s and he was one of the section’s talented young writers.

After the Globe he was on the staffs of the Washington Post and People magazine while also writing songs for Anita Baker, Gary Burton and Pura Fé. He has won both the Stephen Sondheim and Richard Rodgers Awards for his musical writing.

McBride’s parents were an African-American father and Jewish mother (who converted) and the book that put him on the map was “The Color of Water,” his memoir of growing up with her raising the family after his father’s death. He then wrote two novels, “Miracle at St. Anna” (made into a movie by Spike Lee) and “Song Yet Sung” (inspired by Harriet Tubman) and a screenplay for another Lee film, “Red Hook Summer.” He’s also a writer in residence at NYU.

The official biography for the 56-year-old also claims: “He's the worst dancer in the history of African Americans, bar none, going back to slavetime and beyond. He should be legally barred from dancing at any party he attends. He dances with one finger in the air like a white guy.”

His sense of humor is obviously intact, despite the death over the last few years of his mother and niece and a divorce that banished him to his 43d street apartment where he wrote “The Good Lord Bird.”

Circumstances aside, it’s a wonderful piece of writing. The narrator is Henry Shackleford “who claimed to have been the only Negro to survive the American outlaw John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, Va., in 1859.” He’s telling a fellow United Baptist church member of his story in the 1940s when he was 103 or so, somewhat reminiscent of Thomas Berger’s “Little Big Man” and the Arthur Penn film that followed.

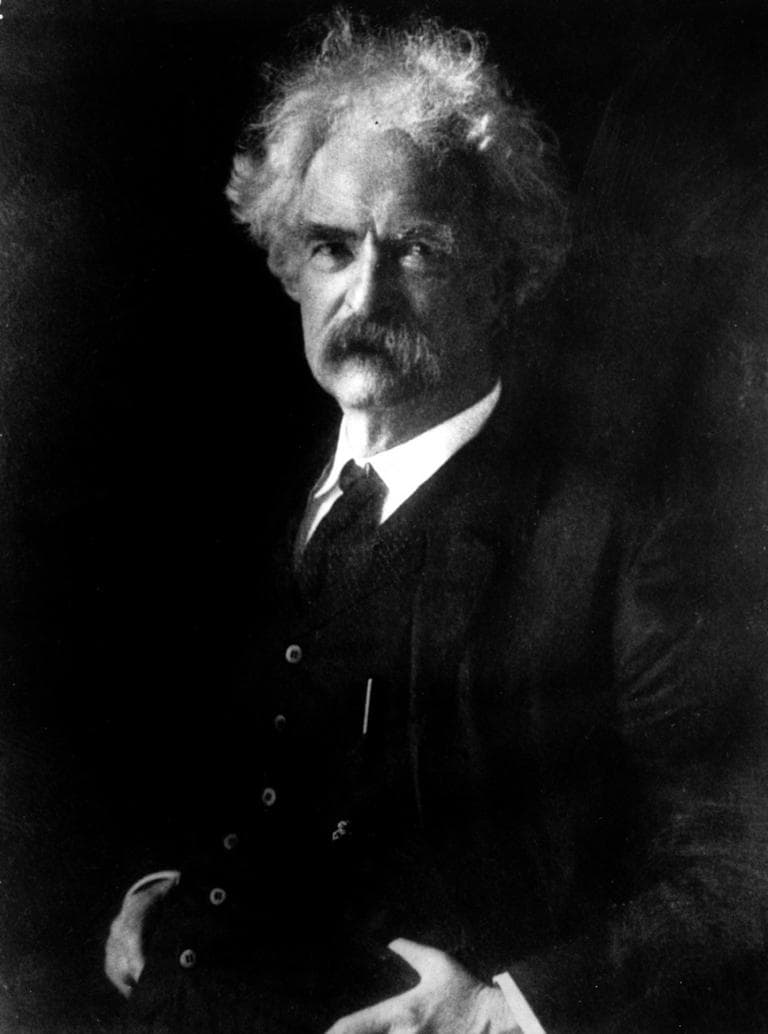

The other writer one can’t stop thinking about is Mark Twain as Shackleford can sound like a black Huckleberry Finn, bearing wry witness to history. There are also hints of Zora Neale Hurston in his fearless use of dialect in making history bristle with wit and wisdom despite the narrator’s lack of education and his instinct for self-preservation above heroism. “I weren’t no more interested in the Bible than a hog knows a holiday.”

Shackleford, in fact, is known as Onion. John Brown, in all his zealotry, storms into the tavern owned by Shackleford’s slave-master, Dutch Henry. Brown, referred to throughout as the Old Man, misidentifies him as a girl and carries him/her off for safe-keeping, dressing him as a girl named Onion.

Advertisement

Thus begins a serio-comical ride into history, not quite a joyride as Harpers Ferry brings the country to the edge of Civil War, but McBride’s tone becomes a joyride for readers.

Here’s how he sizes up Brown early on:

“There weren’t a dumb beast under God’s creation — cow, ox, goat, mule, or sheep — that he couldn’t calm or tame to touch. He had nicknames for everything. Table was ‘floor tacker,’ walking was ‘tricking.’ Good was ‘dowdy.’ And I was ‘the Onion.’ He sprinkled most of his conversation with Bible talk, 'Thees’ and ‘thous’ and ‘takest’ and so forth. He mangled the Bible more than any man I ever knowed, including my Pa, but with a bigger purpose, ‘cause he knowed more words. Only when he got hot did the Old Man quote the Bible exact to the letter, and then it was trouble, for it meant someone was about to walk the quit line. He was a lot to deal with, Old Brown.”

___

Reading the book brought back fond memories of working with McBride and I caught up with him by phone last week. Here’s an edited version of the interview:

Ed Siegel: How did you react when you heard you had been nominated for the National Book Award. Did you celebrate or take it in stride?

“I feel like I won already, just to get to that level. Who knew I would reach this level of novel-writing? The nomination is important not so much because of the potential of winning the award, but to be taken seriously as a novelist. The bridge from nonfiction to fiction is a pretty large bridge to cross no matter how good you are. The way you’re reviewed, the way you’re seen, sometimes it’s hard to be taken seriously when even Newt Gingrich writes novels. I can assure you without reading it it’s no good. To be honest, it’s OK if I don’t win. Some of this stuff, you happen to be standing in the right place when God sneezes

It’s the story of my life.

[Laughs]

Did journalism help you or did you have to get rid of that less fanciful way of writing to come up with a book like this, or any of your other books for that matter?

Journalism was most crucial to my development as a writer. I couldn’t have gotten to this level without it. Particularly in teaching you the need for detail. I tell that to my students all the time. Daily journalism is under duress, but it’s been a real training ground for young writers in America. The editor who looks at you and says “Go out and do that again.” Obituaries, cop stories, facing people the next day if you’re wrong. It’s crucial to the development of a literary writer. The ability to research and interview people. Understanding what the difference is between a mayor and a city manager. I owe a tremendous amount of my success as a writer to that training at the Globe.

So you're saying you owe it all to me?

[Laughs] Hey, who knows where I’d be ...

Anything else about the Globe stick in your mind in that regard, pro or con?

I have wonderful memories. The racial thing in Boston was difficult for me to deal with and I never adapted to that, but the creative freedom at the Globe — you didn’t see that normally in the newspaper world. “The Color of Water” was born at the Boston Globe, with that magazine article. I was sitting in [then magazine editor] Al Larkin’s office. He asked me a few questions and I told him my mother was white and Jewish. That knocked him out of his seat, and he said, "You ought to think about doing that." That’s where it started.

Ernie Santosuosso [the Globe’s jazz critic at the time] and I used to go to jazz clubs together. Those were some of the best days in my life. I was 23 or 24, Ernie was 60. Ernie really had a lot to do with the development of jazz. We used to go to Wally’s [Cafe Jazz Club on Mass. Ave], tiny clubs. He was risking his life going into some of them. He didn’t care, he loved the music so much.

Let’s talk about “The Good Lord Bird.” Did you know you were going to use that voice right from the beginning or did it come as a eureka moment?

I just experimented with a lot of ways to find that voice. I knew I didn’t want it to be a third person account. There’s an old-time way of talking that old black folks in my life spoke. That kind of showed itself and I wanted to see if it was strong enough to hold up. Then I worked in the whole business of him playing a girl. The fact that he was a child just seemed appropriate ‘cause he’s really an old man looking back in 1941, speaking the way an old man storyteller would tell it. I wanted a wide-open perspective, something making everyone including John Brown look stupid. I also wanted it to be funny. He’s trying to make a revolution and the people he’s holding it for don’t show up. It's like me holding a surprise party for myself and not showing up.The writer a lot of people see book is Mark Twain. Were you consciously referencing him?

No. It’s been years since I read “Huckleberry Finn.” I probably have three copies, but I went out and bought it again because so many people were referencing it, though I don’t read reviews at all. When I become an old man I’ll read all the reviews. I don’t think it’s healthy for anyone to read their own press. It makes me think I’m smarter than I am. I try to just operate with blinders on, don’t think about what somebody else did or might do. It Kills creativity. One thing I didn’t like about newspaper, you’d have an idea and present it to a grizzled journalist and he’d say ‘”That’s been done before.” That is a killer of all creativity. I teach one day a week at NYU and I tell them, "Cynicism is the enemy of all great writing. Skepticism is good, it’s the vegetables, green salad and corn of good writing."John Brown is described as both madman and saint in your book. I know you acknowledge the people who’ve kept his memory alive, but there’s something of the Jihadist in him isn’t there? Do you have mixed feelings about him?

Even though he was a terrorist I don’t have mixed feelings I really admire him. I don’t condone the violence, he tried to avoid violence when he could. But I feel 100 percent certain that the accounts of his violence are exaggerated or not put in proper context. As someone who grew up in the church I respect his religiosity. I’m skeptical of his Calvinist notion that he was preordained to remove slavery, but I admire him. And in many ways he’s really tied to the Boston abolitionist movement. Emerson, Henry David Thoreau all admired him in one way or another. Julia Ward Howe. When he died he never got much out of what he did. His wife and children suffered tremendously.

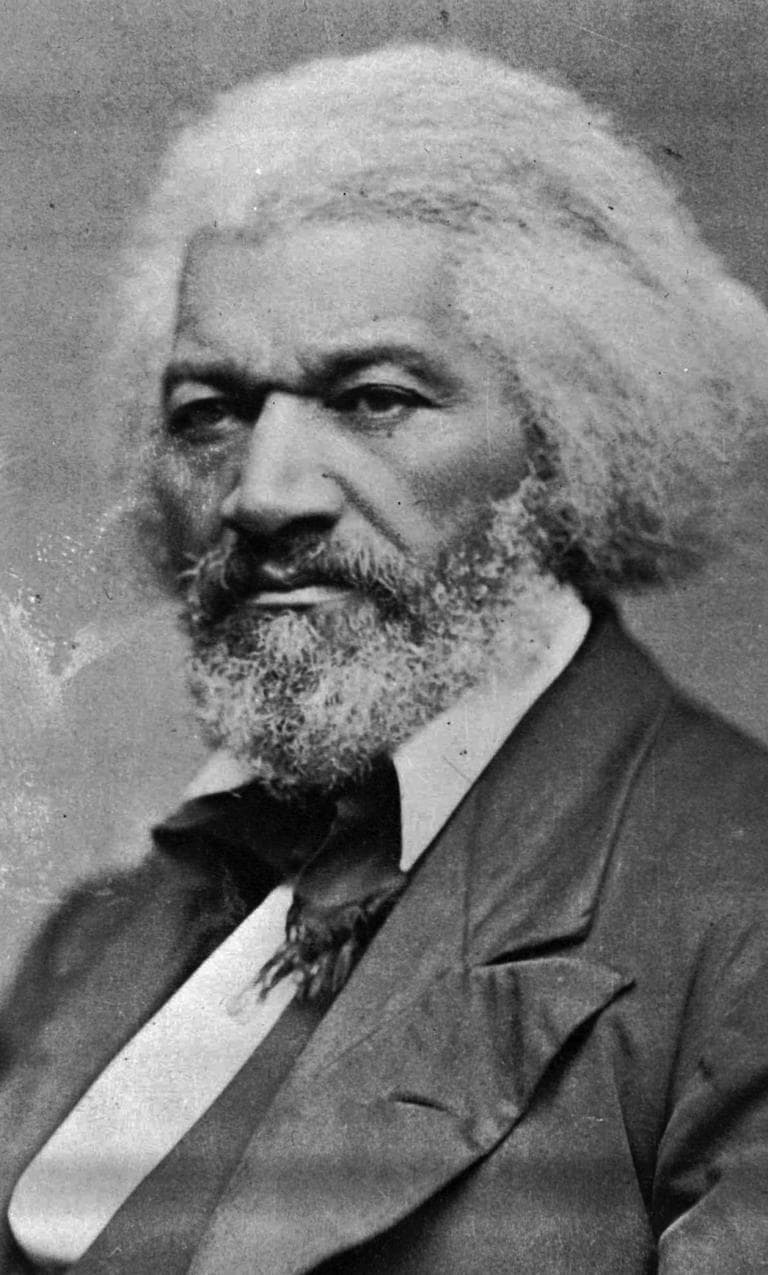

Frederick Douglass also puts the moves on Onion thinking he’s a 12-year-old girl.

That was just me having fun, but it’s true that he had a white mistress and a black wife and they lived in the same house for a while.

__

McBride is now touring with a band, playing gospel songs and reading from his book. There aren’t any plans at the moment for him to come to Boston. There’ll no doubt be a lot of old friends in attendance if he does.

This program aired on November 6, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.