Advertisement

'Whitey' — A Film With A Bit Of Gray From Sundance

PARK CITY, Utah — Last week’s world premiere of “Whitey: United States of America v. James J. Bulger” beguiled Sundance Film Festival audiences with a high-octane account of the multi-directional corruption between Boston’s infamous crime boss and law enforcement.

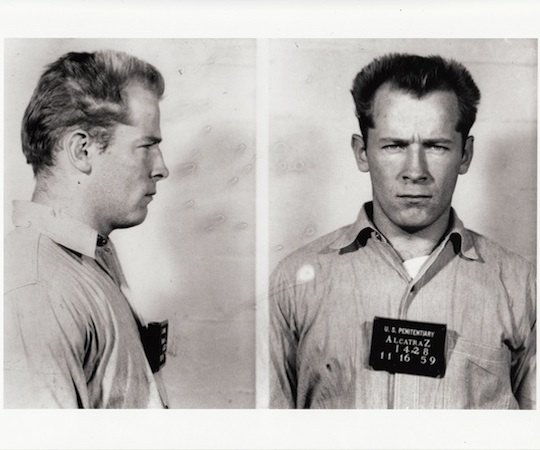

In August 2013, James “Whitey” Bulger was convicted of 11 murders, drug trafficking, racketeering, extortion, money laundering, and other crimes. The documentary largely focuses on his eight-week trial.

This Thursday night, the documentary’s director, Academy Award nominee and six-time Sundance filmmaker, Joe Berlinger, will bring Sundance close to Bulger’s old turf.

The sold-out Coolidge Corner Theatre screening is one of nine 2014 films that is traveling to art house cinemas across the country as part of Sundance Film Festival USA. All events take place Jan. 30 and include time for talking with talent such as the director, actors, or documentary subjects — an opportunity that the festival prioritizes at public screenings in Utah.

For many of the Boston-based interviewees in “Whitey,” the night at the Coolidge will be an extension of the festival’s non-stop opening weekend party. Bulger defense attorneys J.W. Carney Jr. and Hank Brennan, trial witness Steve Davis, and WBUR’s David Boeri, a consulting producer on the film, all traveled to Park City for the premiere.

“Whitey” was co-produced by CNN Films, a new division within CNN devoted to long-form nonfiction, and will be broadcast at a time to be determined in 2014. While no deal was finalized at the time of our interview midway through the festival, Berlinger remains optimistic that “Whitey” will also have a theatrical release.

“Whitey” sets the lawless Boston scene with a hard rock score and sweeping aerial shots of South Boston and Boston Harbor, leading to Moakley Courthouse. Incidentally, the courthouse was the backdrop for controversy in another Sundance documentary, “The Internet’s Own Boy," about the untimely death of a Aaron Swartz. Swartz was charged with illegally downloading scholarly articles through a false MIT student account and took his own life in early 2013.

Advertisement

As for “Whitey,” the storyline initially treads over familiar territory to give context to Bulger’s rise to power. Some of the same interview comments and scenes can be found in the locally-produced “Whitey Bulger: The Making of a Monster," which aired on Discovery before the trial began. The more studious and less theatrical “Whitey” then shifts the focus to the trial and the question of whether or not Bulger was an FBI informant.

The lack of clarity on Bulger’s informant status is “central to the case,” said Berlinger to a Sundance audience Jan. 25. He picked up on the issue, he said, because other media shrugged it off as a sideshow. “If he wasn’t [an informant], then [law enforcement’s] corruption ran even deeper,” Berlinger said. “The people of Boston deserve answers for questions still swirling around this case.”

Berlinger has a history of making films that skillfully oscillate between opposing sides during criminal trials. “Brother’s Keeper” (1992), the “Paradise Lost” trilogy (1996-2011), and “Crude” (2009), in which the director found himself in the middle of a freedom of speech battle, cause one to pause, reconsider, and realign sympathies a few times before they end.

Though Berlinger has said publicly several times since the premiere that he is not a “Bulger apologist,” “Whitey” oscillates, too. For one, Bulger’s defense team gave him far more access than the prosecutors (Fred Wyshak, Brian T. Kelly, Zachary Hafer), who limited their time to a two-hour interview after the verdict was rendered. For another, Berlinger went to screen with the trial he was given, so to speak. Had Bulger’s defense been able to argue his case for immunity, had Bulger chosen to testify, “Whitey” could’ve been a far different, perhaps more decisive film.

Plus there’s the fact that even the most mindful citizen can hardly keep track of the true-crime drama’s complex array of characters. Check out the bio section of WBUR’s Bulger on Trial as a frame of reference.

What sets “Whitey” apart is the unprecedented audio access to Bulger through a filmed phone conversation between him and Carney. When asked if he was ever an informant, Bulger recalls his first incarceration, “I never, never, never cracked.” (Meanwhile, in the “Whitey’s First Arrest” segment of “The Making of a Monster,” the voice over says, “On the way to prison [in 1956, Whitey] sells out another accomplice and shortens his sentence.”

Fully aware of the dozens of accounts — both fiction and non — of Bulger’s crimes and evasion of punishment, Berlinger said that he’s interested in the subjectivity of all media, how news is consumed, and how news stories are reduced to black and white. In other words, Berlinger is deeply committed to the gray.

By and large, Bulger’s dialogue in “Whitey” reinforces the mythology that he is a criminal with a code that includes and remaining loyal to the end. His poor-me reaction to being betrayed by right-hand man, Stephen Flemmi (admitted FBI informant and cooperating witness against Bulger), drew laughs from the audience.

Because cameras and recording devices are not allowed during federal trials, Berlinger made appropriate use of re-creation for the first time in his otherwise cinema verite career. Some participants willingly recorded their testimony from transcripts, some professionals provided voice work, and mock trial scenes were shot at Suffolk University Law School.

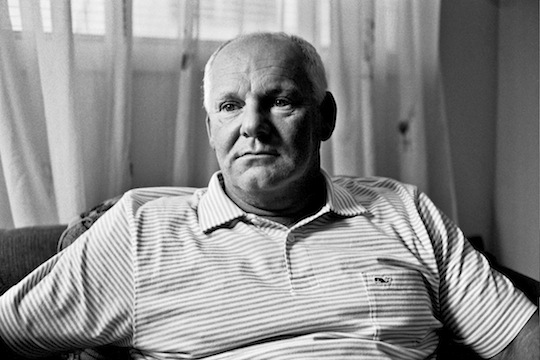

But being there is what made for one of the most powerful storylines. Berlinger was in the back seat with a camera when trial witness Steve Davis, whose sister Deborah Davis was murdered, learns of the death of his friend and fellow Bulger victim, Stephen Rakes. Rakes had already set a sympathetic tone in “Whitey” and audiences expressed audible shock over the news.

“I don’t have any faith no more,” says Davis, shaking his head. “I’ve had a lot of hurt, Joe.”

A fair amount of screen time passes before the film revisits Rakes and says that he was murdered, leaving audiences to wonder what exactly happened. Berlinger assured them he did not intend to suggest government wrongdoing. “I don’t think the corruption is that overt,” he said in Q&A.

Yet even though Rakes’s murder had nothing to do with the Bulger trial, as Berlinger went on to explain, audiences of this film go home feeling unsettled by the sting of violent crime.

Erin Trahan edits The Independent, an online magazine about independent film and is moderating the Winter 2014 season of the The DocYard.

More From Sundance: