Advertisement

Harvard’s Famously Damaged Rothko Paintings 'Restored' With Light

Resume

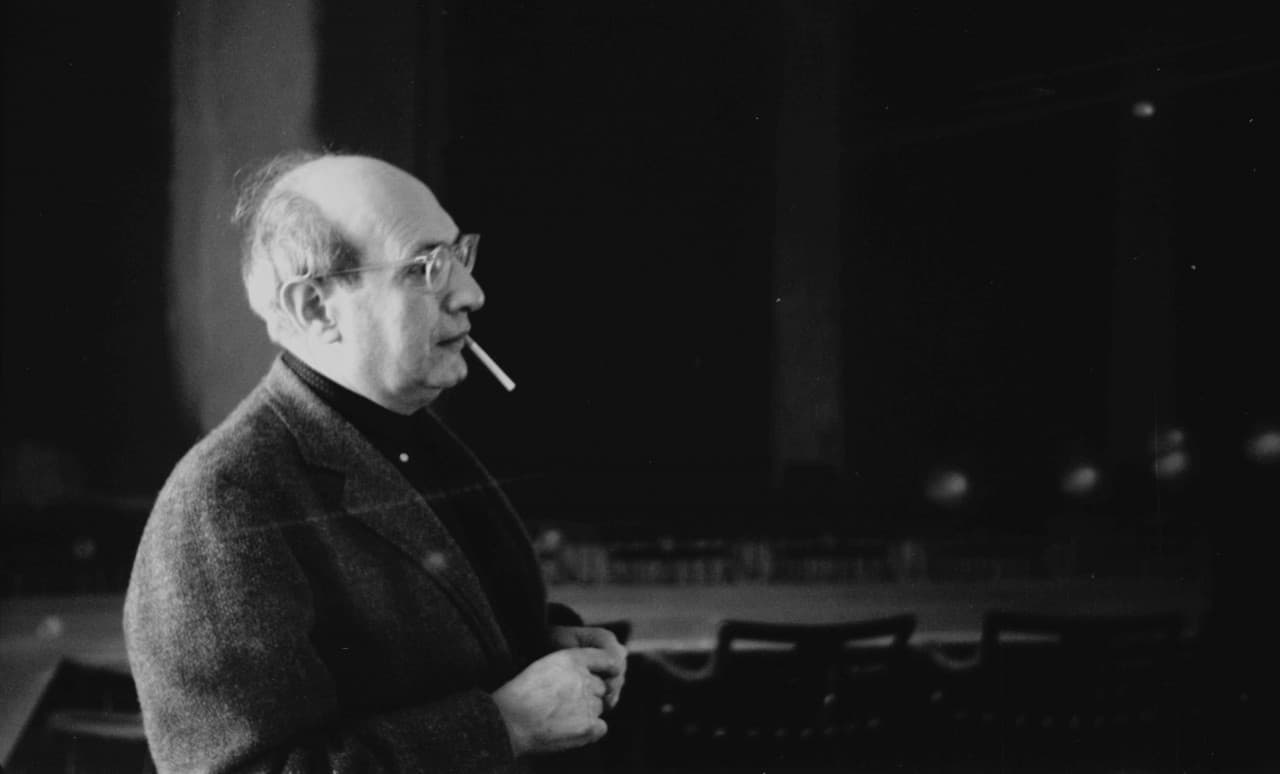

Five monumental paintings by Mark Rothko that have become the stuff of art world legend — and art world nightmares — are being revived.

The post-war abstract artist donated the plum-and-crimson-colored murals to Harvard University in 1963. But they quickly faded in the sun-drenched room where Rothko insisted they be installed.

Damaged beyond repair, the paintings were banished to dark storage in 1979 and have only been seen by the public three times since.

But now new technology will allow visitors to the Harvard Art Museums to see the storied Rothko murals the way they looked 60 years ago.

For Rothko fans — and there are a lot of them — sitting in front of one of the abstract artist’s expansive paintings is a spiritual experience.

For collectors, his mid-20th-century works are a hot commodity. Just last week, a Rothko work sold for $50 million at a London auction house.

That’s one reason why retired curator and conservator Marjorie Cohn calls the story behind the Harvard Rothkos a head-scratcher.

“It is a strange tale, especially now that the art market seems to be out of sight in terms of the art prices,” she said sitting at her kitchen table in Arlington. "And Rothko’s paintings, particularly the well-preserved ones of course, are right at the top of the market. Everybody wants a Rothko, and the fact that Harvard has a whole room of them that nobody sees is the other side of the story.”

It all began in the early 1960s. At the time, Cohn was an apprentice conservator at the Harvard Art Museums. She saw — and even touched — the commissioned murals that were created for a new space at the university’s Holyoke Center. Rothko worked on them for years. Cohn recalls it being an all-hands-on-deck moment when the painter arrived.

“So I, and everybody else in the conservation department, stretched the murals for Rothko. And he came to select which murals went where,” she said with a smile.

The team installed five out of six canvases. Cohn says Rothko — who was known to be severely depressed — seemed happy.

“The atmosphere then was so positive,” she described. “He had nothing but praise for our efforts in getting things ready for him … and we of course were just thrilled to be working with such a famous artist.”

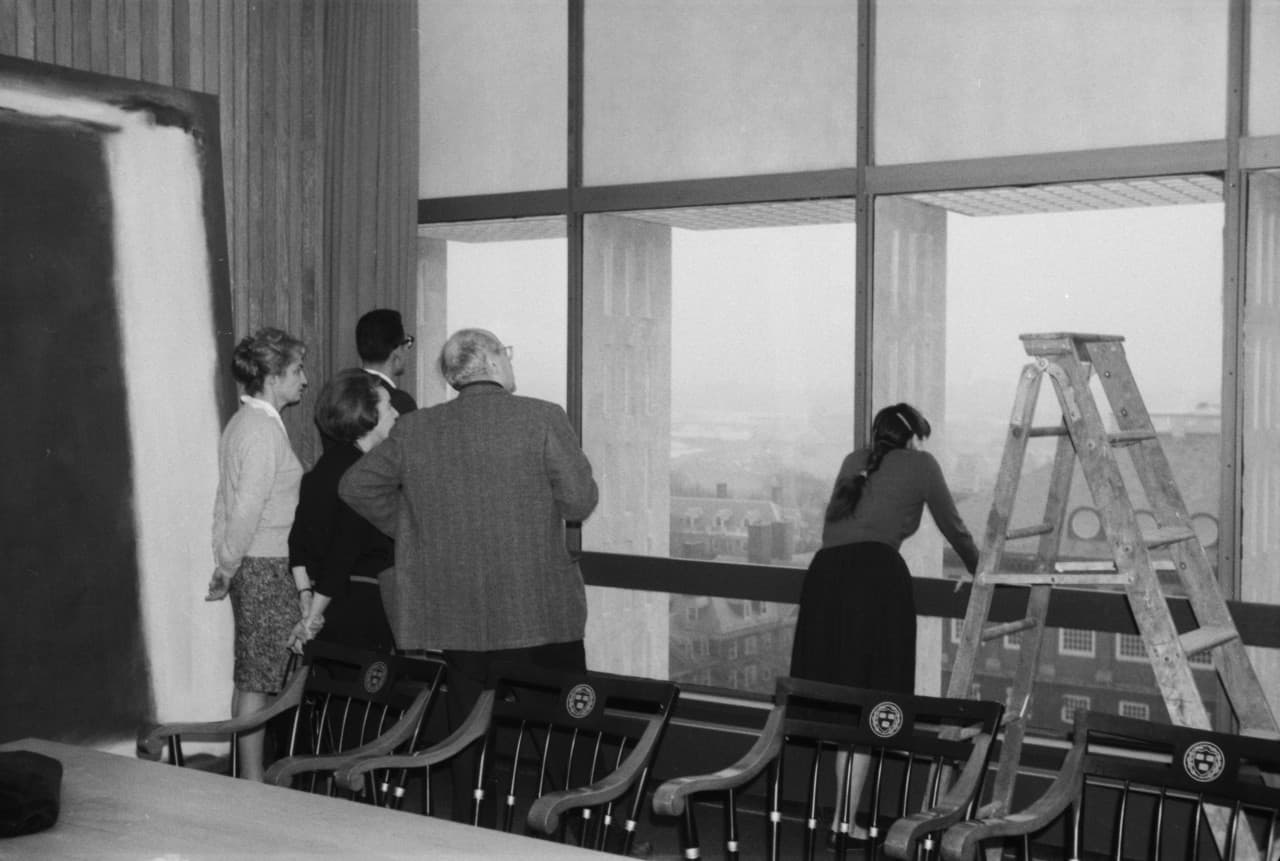

When Rothko donated the works, he stipulated that they always be hung as a group in a penthouse dining room with the drapes drawn. Cohn says the room was known for its killer view of the Charles River.

“And my boss was on the telephone all the time to the manager of the space about making sure those curtains were kept closed," Cohn said. "But off course they weren’t. Everybody went there for parties, they could care less about Rothko murals. They opened the curtains to look at the view. You really can’t blame them.”

The partiers also managed to splatter the paintings with food and cocktails. That abuse — combined with dramatic sun damage — has created the paintings’ notorious mythology.

“They’ve been mythic, partly of course because it wasn’t too long before they were actually taken down and put out of sight,” Cohn said. “So everybody knew they existed, but nobody could see them.”

Modern and contemporary art curator Mary Schneider-Enriquez saw the dramatic square and rectangular panels right before they were taken down in 1979. She was an undergrad and says the amorphous figures Rothko painted appear to be entering portals.

“Each of them kind of floating on this deep crimson, plum ground,” the curator described. “Because of both the darkness and the sense of light he conveys, they really take you into the space of the canvas in a way that really makes you pause and contemplate and feel all at once.”

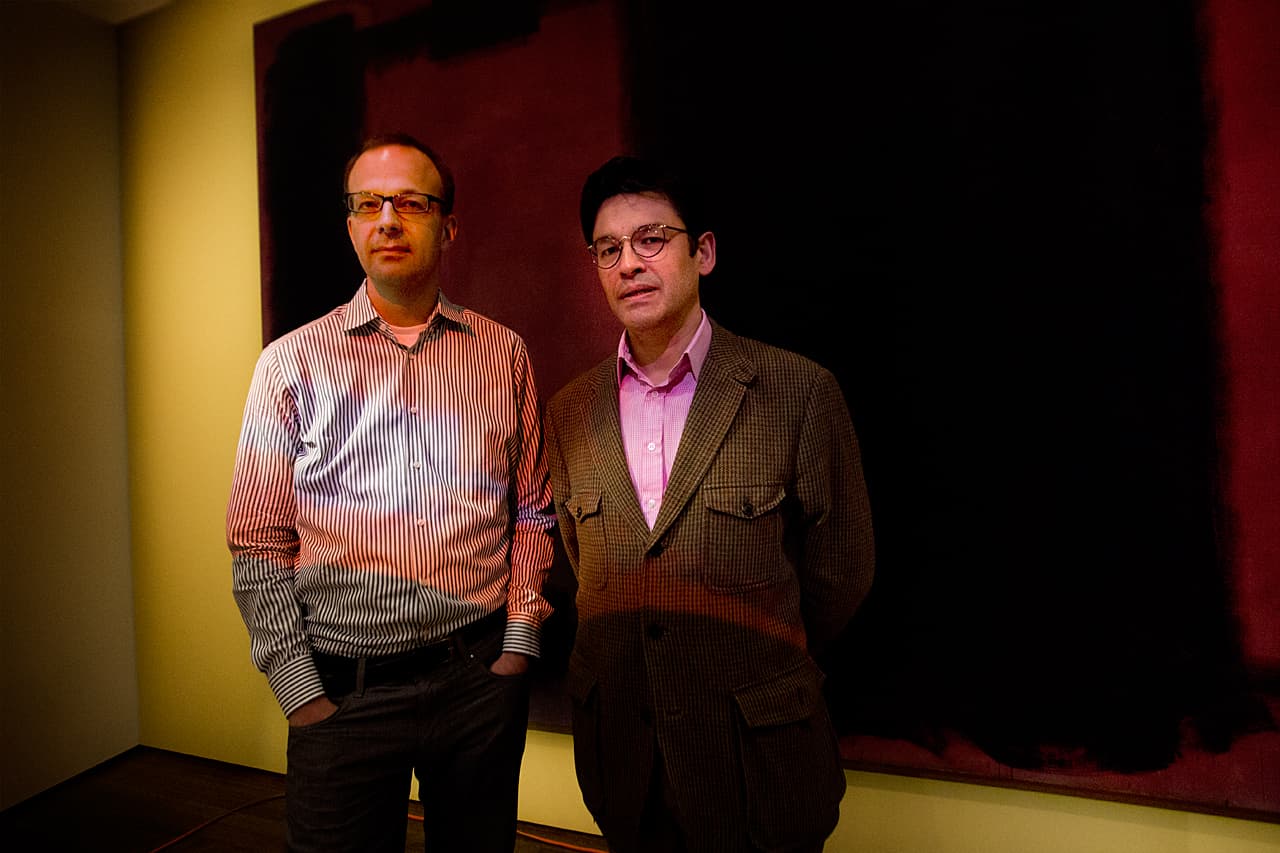

Now Schneider-Enriquez is curating the upcoming fall exhibition of the Rothkos, which were restored using a new, noninvasive technology.

The gallery was designed to the exact dimensions of the Holyoke room where the Rothko murals originally hung. Each of the five murals is illuminated by a projector suspended from the ceiling. When you stand in front of them, the paintings appear resurrected.

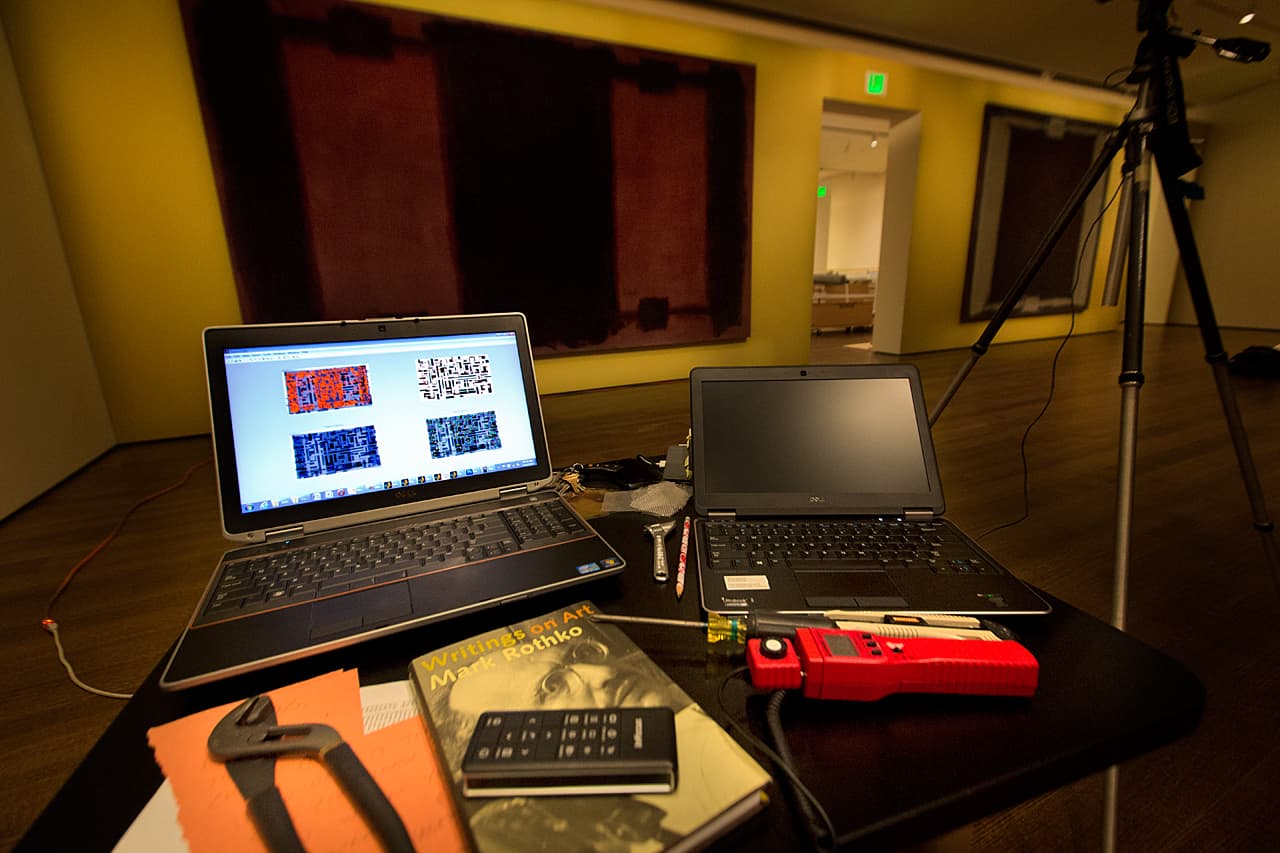

Harvard conservation scientist Narayan Khandekar calls this a new solution to an old problem.

“What we’re doing is using light as a restoration tool, a retouching tool," he said. "We’re using light to fill in those missing areas.”

A team developed, and is still tweaking, this new technique. Former Harvard Museums conservationist Jens Stenger, now with Yale, worked with the MIT Media Lab’s Camera Culture research group and Swiss researchers to program digital imaging based on the original colors.

Stenger says they needed to do this because the type of paint Rothko used could not be restored physically.

“Rothko made his own paint," he said. "He used animal glue, and he heated it up and poured in dry pigment. He used whole egg as a binding medium to disperse the pigment."

It was this secret recipe that contributed to the uneven fading of the murals. Stenger also says the animal glue is completely soaked into the canvas, which has been especially challenging.

“It’s like a stain," he said. "If you would start in-painting this you would completely remove the artist’s hand, you would remove the brushwork.”

And that would break the cardinal rule of art conservators: The artist’s intent must remain intact.

After painstaking analysis and research, the team was able to map the lost color and then project light on the paintings to compensate for the damage. The Harvard Art Museums is the first to use this system in this way, and the folks there want the Rothko exhibit to stimulate debate.

Carol Mancusi-Ungaro, director of the Center for Technical Studies Of Modern Art at the Harvard Art Museums and associate director of conservation at the Whitney Museum in New York, says any new restoration technology is likely to raise questions, especially at the Harvard Art Museums, home to the oldest art museum conservation center in the U.S.

“I think it raises questions of how far one can take it, and how one should take it in the future,” she said. “The field rises to meet the challenges, and I think this is the logical next step.”

Mancusi-Ungaro calls it a timely confluence of art and science.

She’s been coming to terms with Rothko’s often-mysterious materials and brushwork for years. As head conservator at the Rothko Chapel in Houston, another famed site-specific installation, she worked to repair faded whites, and polymer chemists helped develop a treatment. Mancusi-Ungaro says the circumstances were different there, but at the same time, she says this sort of “compensation” for areas of work that have been damaged is what conservators do.

The Harvard Art Museums have been keeping the murals under wraps. No critics are allowed to see them until the exhibition opens in the fall. But perhaps the most important review would come from Rothko’s son, who was able to see the illuminated murals this past November.

“I have to say I wasn’t sure what to expect,” Christopher Rothko said on the phone from his New York office. “I’ve been hearing about this for a couple of years and we want to have a lot of faith in technology, but of course technology is not just a push the button fix for everything.”

So, what did Christopher Rothko think of the color-corrected works?

“I got the goosebumps!” he recalled, laughing. “I was really struck right away not so much by the color, but by the way they still felt like paintings. Because it’s just projecting a transparent light on there — you still have the feel of the brushstrokes, you still have the feel of the canvas, you can still feel that this is a real object.”

And for the younger Rothko that’s what makes it feel believable.

“My father’s brush strokes are still there," he said. "And the texture of the paint, it’s all still there.”

Christopher Rothko actually provided the missing link that brought this all together: a sixth panel the artist decided not to hang at Harvard. It went home with Rothko to New York where it stayed rolled up, safe from light damage. With access to that, the conservation scientists were able to identify the original color.

But there has been tension between the Rothkos and Harvard over the years. His son says in the 1980s some people seemed to be blaming the artist, who committed suicide in 1970, for the the work’s deterioration.

“He always talked about works that are timeless,” Christopher Rothko said, of his dad. “Well, if the clock only runs 10 years that’s not timeless in most people’s view! So we were upset that they had so thoroughly misunderstood my father’s intentions and thought that he didn’t even care about his own work, which couldn’t been further from the truth.”

Christopher Rothko isn’t sure what his father would’ve thought of his work being “fixed” with projected light and software. The artist wrote extensively about the dangers of technology. But right now his son is just relieved that the mythic Harvard murals will be back in the public eye.

"Hopefully people will have a profoundly moving, emotional, philosophical experience," he said. "You know, everybody has their own experience. That was my father’s intention, and ultimately that’s why people love his work so much.”

When the Harvard Rothko murals are open to the public, scholars of the acclaimed artist will be able to delve into this period in the painter’s career. And Rothko fanatics will have a new option for communing with these long elusive works.

Correction: Due to a technical issue, an earlier version of this story contained two Rothko works with incorrect coloring. The corrected paintings have been uploaded and we regret the error.

More Photos:

This article was originally published on May 20, 2014.