Advertisement

Why Women Don't Study Engineering — And What 1 Mass. College Is Doing About It

Resume

A 2011 study by the American Society for Engineering Education found women accounted for only 18 percent of undergraduate students in engineering.

At the University of Massachusetts Amherst, that number is even lower: only 291 women out of 1,833 undergraduates, or 16 percent, at the College of Engineering this year.

Engineering As A Performing Art

Kelly Kennedy liked physics and math when she was growing up. But she found that was not the case with a lot of her classmates.

"For some reason, a lot of girls don’t take the AP Physics classes or AP Calc classes and more guys do," she said.

Kennedy just graduated from UMass Amherst's College of Engineering with a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering, an especially unusual field for women.

"A lot of guys will become interested in cars," Kennedy said, "and then someone will tell them, 'You should become an engineer and then you can design the cars,' but I think as girls, we don’t get that as much."

And it's not just mechanical engineering. It's engineering in general.

"Culturally, we tend to think that engineering is not for women," said Yevgeniya Zastavker, an associate professor of physics at Olin College of Engineering, a small school of fewer than 400 students in Needham, founded in 1997. "Engineering is mostly for men."

From its beginning, Olin wanted to attract more women to engineering.

Olin's president, Rick Miller, said the way engineering colleges teach engineering turns women and other students away who might otherwise be great engineers. He views engineering as a performing art. But he compares the way most schools teach it to what would happen at a music school where students don't touch instruments until their senior year.

"You’d be talking about point and counterpoint, harmony and melody and tempo and all the things that are behind the structure of the way music is created," Miller said. "In the fourth year, if you're still here, we’ll ask you to play a scale on a real violin and then we’ll give you a music degree."

When those freshman and sophomore engineering courses are centered on theory and math and problem sets, they can be daunting.

Caitlyn Butler, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at UMass Amherst, said women often respond differently than men to the grades they get in those courses.

"I think there’s a confidence issue," Butler said. "I think there’s kind of a gender gap there. When a male student gets their first test back, and they get a less-than-perfect grade on it, they’re like, 'All right! I passed. I survived. I did all right.' And then a girl may say, 'I didn’t do so well on this. I’m not cut out for it.' ”

A colleague of Butler's, Shelly Peyton, an assistant professor of chemical engineering at UMass Amherst, points to a feedback loop that also keeps women from studying engineering.

"Girls get a little frustrated when there’s only 10 girls in that class of 70," Peyton said. "And I think that leads into this confidence issue, too. 'Wow! I’m kind of alone here.' "

Beginning Early

Professors and students report that men don't make it easy for women in their classes.

Paula Santiago is pursuing a master's degree in engineering management at UMass, where she also studied engineering as an undergraduate.

"There’s all kinds of stereotypes," she said. "I was in a lab a couple of hours ago, and the way men talk about women sometimes, like they’re lesser or they might not make the best conclusions. 'They’re dominated by their emotions than their brains.' I think women are generally scared, maybe, of the field, and so they feel maybe go to an easier field."

The director of diversity programs at the UMass Amherst College of Engineering, Paula Sturdevant Rees, said to get more women involved in engineering, you have to begin early.

"Some studies are showing that as early as fifth grade girls have decided whether they feel they can do math or not, and so if you don’t intervene then and show them different ways math is used and why math as a tool is really cool and really fun, you risk even losing them as early as fifth and sixth grade," Sturdevant Rees said.

Olin College has demonstrated that it can attract women to engineering. Professor Zastavker says, in part, it's because Olin has redefined engineering.

"It’s about us," Zastavker said. "It’s about humans; it’s about what we as humans need and how we can better our lives, and if we understand engineering in that way, we probably will attract more women, but it needs to start very early."

And students at Olin learn in a way many academics say is especially attractive to women.

"One of the ways that we are experimenting with is so-called project-based learning," Zastavker said. "It allows students to be autonomous learners. We ask them to develop their own goals and move toward those goals."

Challenges For Public Universities

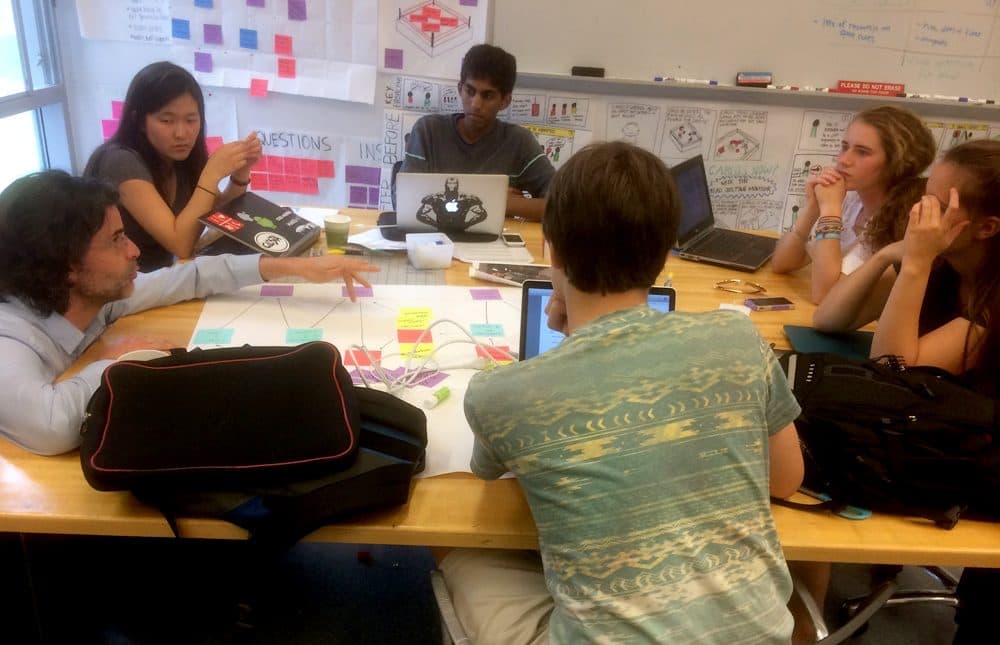

The mandatory sophomore-year class, User-Oriented Collaborative Design, is held in a multicolored classroom: students' post-it notes are all over the walls. The cacophony you would expect as students come into class remains throughout the class.

On one recent day students clustered into problem-solving teams. They began the semester with a group of people whose needs they must serve, and, with their team, develop a technology that improves the lives of the users.

"For me, the reason that I chose Olin was I really like the way they've said an engineering education doesn't have to be sitting in a classroom and being lectured at for the most part," said Sophie Seitz, who was part of a team trying to come up with technology that would help medical providers who volunteer abroad.

"We’re doing engineering because it’s about people, with people and not in spite of people," said Associate Professor of Design and Engineering Benjamin Linder, who teaches the design course. "They start with a group of people and they end with a proposal for a product or service, something that would add value to their lives."

At UMass Amherst, Sturdevant Rees points out another reason women don't study engineering: Women just don't see that many women engineers.

"Careers in law and medicine are much more tangible to them," Sturdevant Rees said. "There’s more role models out there."

Olin College is successful at attracting women because, from its beginning, its freshman class was half women.

In recent years, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has had similar success. Women now make up 42 percent of engineering undergraduates at MIT.

At UMass Amherst, Peyton points out it's not so easy.

"At a private school, you have a lot more control over your admissions," Peyton said. "You can diversify your class on purpose. Unfortunately, UMass Admissions controls that, and they’re trying to get the best kids, and I think that split is about 50-50, but they’re not controlling how many of those women are going into engineering versus..."

"Business," a colleague interjected.

"English majors," Peyton continued.

So the biggest factor in attracting women to engineering may be simply to create a climate where half your students are already women. Easy to do for private colleges, not so easy for public universities.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly spelled Shelly Peyton's last name. It has been updated with the correct spelling, and we regret the error.

This article was originally published on May 27, 2014.

This segment aired on May 27, 2014.