Advertisement

At 200, The Handel & Haydn Society Is Celebrating Its Storied Past And Survival

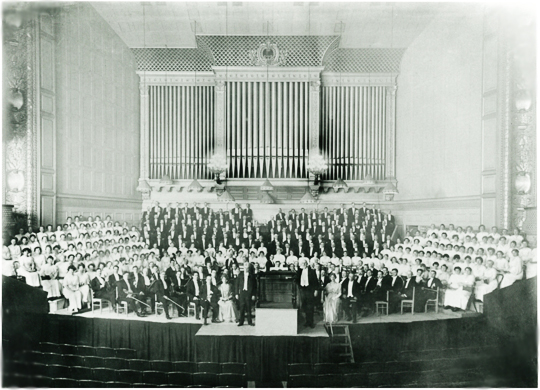

ResumeBoston’s Handel & Haydn Society has been making music for 200 years. It’s the longest running performing arts organization in America, and is perhaps best known for its signature concerts of Handel's masterwork "Messiah."

This weekend, the period instrument orchestra and chorus will celebrate its storied past and survival with a concert at Symphony Hall. I went to a rehearsal to find out more about the group's evolution.

Historically informed performance — HIP for short — is how the Handel & Haydn Society defines what it does. Its professional singers and players work hard to create something of a musical time machine, by making choral pieces and iconic compositions sound like they did in the Baroque and Classical periods, from 1600 to 1830.

But flash back 200 years from today to the society's beginning — that's when Executive Director Marie-Helene Bernard says passionate amateur singers and musicians started building a decidedly contemporary vehicle for popular, largely sacred music.

"In 1815, Haydn has been dead for about six years, his music is still very much in vogue in Europe, and these musicians really wanted to bring it to America," she explained.

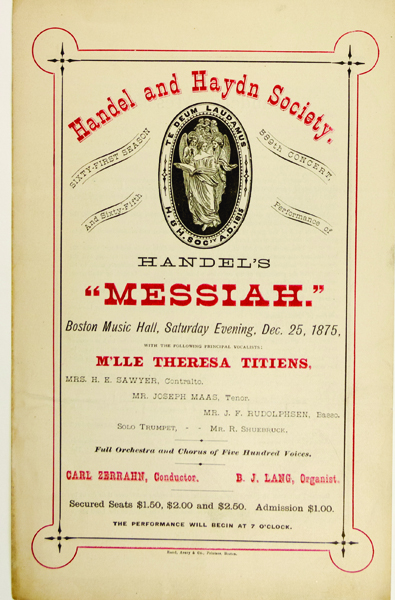

The society’s first concert was Christmas day 1815 at King's Chapel in Boston. A few years later, the Handel & Haydn Society broke new ground with the first U.S. performances of Handel's now iconic "Messiah" and Haydn's epic "Creation."

"Handel & Haydn gave the premiere of many works that are now part of the regular repertoire, but that was new in the day," Bernard said. "Bach’s 'St Matthew Passion,' Verdi's 'Requiem' — which was first heard in the U.S. here in Boston with the Handel & Haydn Society. And the first performance of Beethoven 9."

In 1823, the society even requested a commission from Beethoven, but the composer died before he could fulfill it. Handel & Haydn performed at a long list of historic occasions, including memorial services for Presidents John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and John Quincy Adams. Also at the Emancipation Proclamation celebration in 1863, where Ralph Waldo Emerson orated. Through the years, the society has focused on the power and beauty of the human voice.

Before rehearsal, soprano Brenna Wells illustrated her grasp of the repertoire by singing a plaintive line ("O sleep, why dost thou leave me?") from Handel's opera "Semele." She says she’s honored to be part of an organization that is so steeped in history.

"The transformations and incarnations the society’s been through — I just think it's amazing that it's still here," Wells said.

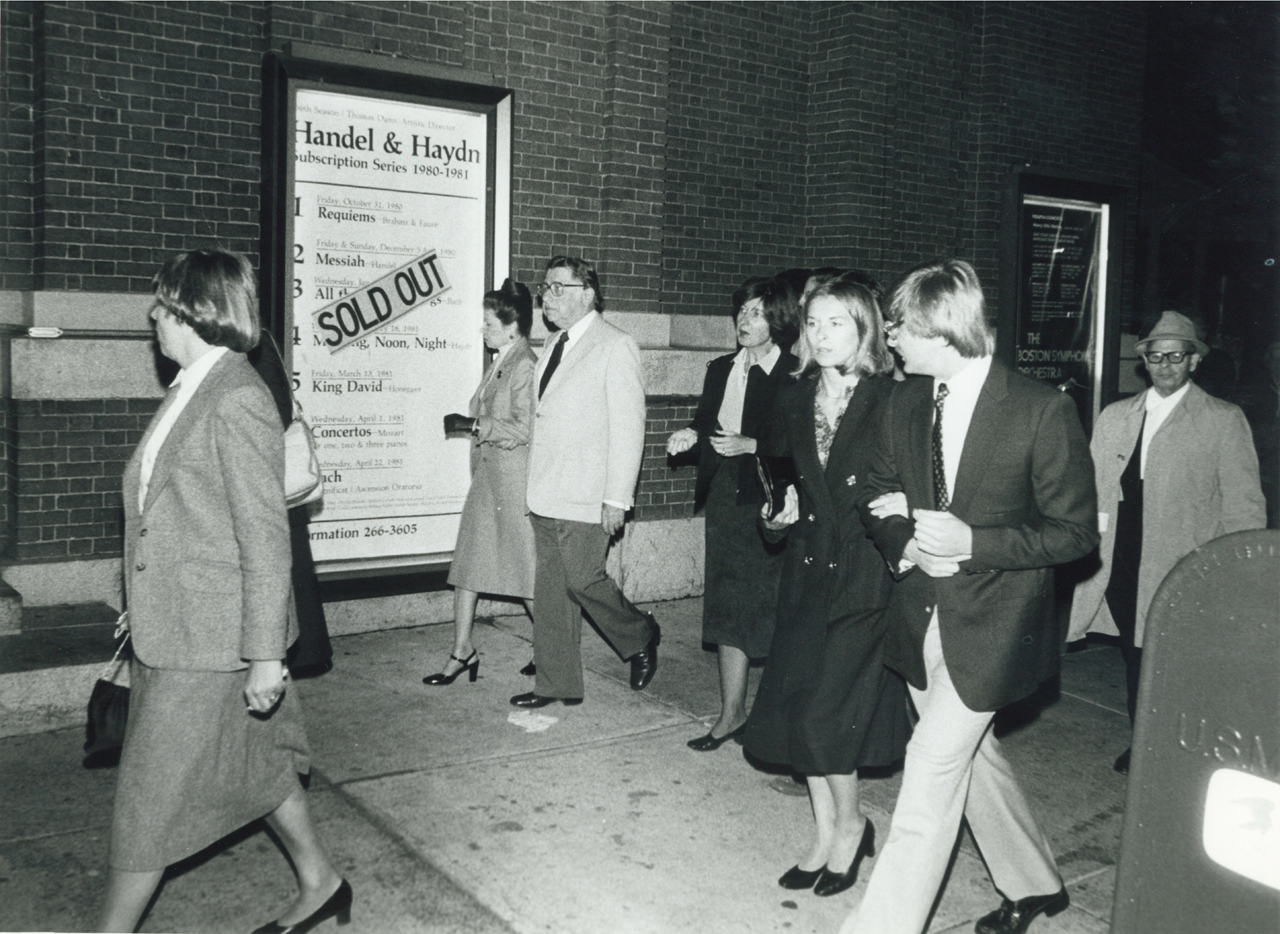

There have been ups and downs, in-fighting and financial struggles over the decades. The chorus’ role has transformed, too. For the first 100 years of its existence, the voice dominated the society's aesthetic. But jump to the 1960s when one brutal review stoked a major modification. Boston Globe classical music critic Jeremy Eichler explained the lacerating piece came from another Globe reviewer named Michael Steinberg.

"What Steinberg knew was that there was this whole thing out there called the 'early music movement' — that it was taking shape in places like New York, where conductors like Thomas Dunn were thinking about this repertoire in entirely new ways," Eichler recounted. "They were trying to figure out the numbers of how many singers were involved in these performances back in the composers’ own days."

Thomas Dunn was appointed to be the society's music director in 1967. He embraced the idea of the "historically informed performance" by shrinking the chorus to about 30 singers and led a more intimate, game-changing performance of the "Messiah" in 1977.

Another major change came in 1986, when Christopher Hogwood, an early music devotee, joined the society as artistic director. He ushered in the society's switching from modern to period instruments.

Robert Nairn played a few variations of double bass. He teaches historical performance at Juilliard and says the instrument changed to suit repertoire from different eras. Nairn has been with the Handel & Haydn society for 11 years.

"The instrument that I’m using for the current program is a copy of an instrument that was built in 1730 in Vienna," the musician explained while holding it upright for me to inspect. "It has frets, it has five strings. This is technically what violone, so it’s a precursor to a double base in some ways."

Nairn's bow is from the 1700s, and the bass's strings are made of sheep gut.

"It has a much raspier sound," he said, running the bow across the thick strings. "But it also has a much richer sound. There are more high harmonics and a great deal of color that’s different than metal strings."

But there's a downside — sheep gut strings, highly sensitive to humidity and even light, go out of tune constantly.

Conductor Christopher Hogwood left Handel & Haydn in 2001. But the current music director, Harry Christophers, has continued to embrace period instruments while also nurturing the chorus. And he says he'll be thinking of Hogwood — who died just two week ago — at this weekend's performances.

"What he did was quite staggering, and [his death] is tragic," Christophers lamented. "But in many ways we can use that as a wonderful celebration of his work and what he did for the society."

The Handel & Haydn Society has been performing “Messiah” every year since 1854. To celebrate its 400th performance of the piece last year — and the 200th anniversary — Handel & Haydn is releasing a new recording on Oct. 14. An exhibition about the society's history opens at the Boston Public Library in March, and a 250-page coffee table book by classical music critic and scholar Jan Swafford has also been published, for which I am grateful, because I humbly admit this one little story just skims the surface.

The Handel & Haydn period orchestra and chorus takes the stage Friday and Sunday at Symphony Hall.