Advertisement

As Health Incentives Rise, Many Get Paid To Work Out And Eat Kale

Laura Smith scans a wall of pasta sauce jars at a Shaw’s in Waltham, and reaches for her favorite.

“It looks like it would be fantastic for you,” Smith says, showing off the label. “It looks like someone just plucked a bunch of tomatoes and put them in a jar.”

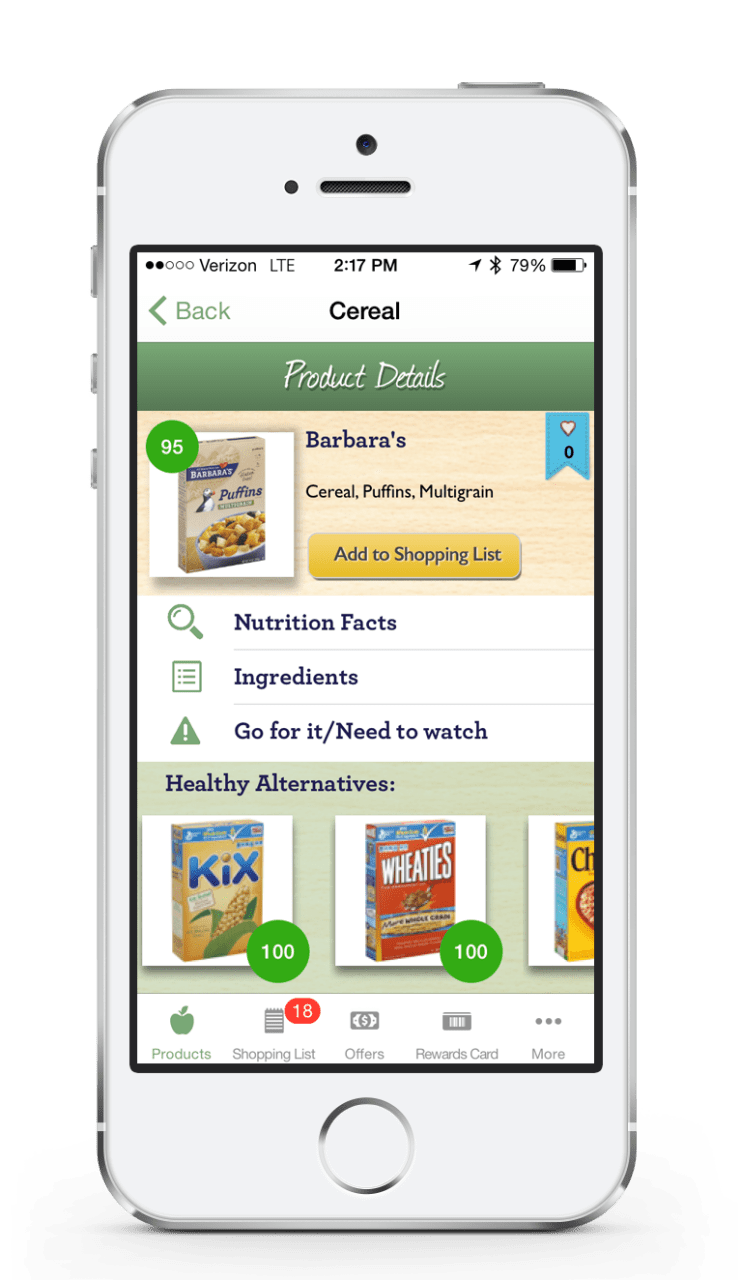

But when Smith scans the jar’s bar code, using an app on her phone, her smile fades.

“It’s a 33,” she says and then pauses. “Wow, 33?”

That’s 33 out of 100 on a healthy food scoring system developed by Newton-based Nutrisavings. Not good. Smith types pasta sauce into the Nutrisavings app and finds one that scores much better, at 75.

“Francesco Rinaldi,” Smith says, turning the jar in her hand. “No salt added, it’s a healthier option, that’s what I’m going to go with.”

Nutrisavings scores more than 200,000 foods on a scale of zero to 100. Sodas are typically a zero. Many fresh fruits and vegetables are up near 100. The company has partnerships with 80 supermarket chains around the country, including Shaw's, where the score for everything Smith buys is totaled when she checks out.

Smith earned $10 this month just for using the program. She’ll get another $10 every month that her average score is 60 or higher.

“That’s $20 essentially free money just by making modestly healthy decisions and going to the store, which are things I’m going to do anyway,” Smith says.

Who pays? Her health insurance plan, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care.

The goal is “to get people to understand the value of what they’re putting in their mouths,” says Sue Amsel, a senior product portfolio manager at Harvard Pilgrim.

These days, most employers dangle some kind of incentive in front of you, hoping you’ll get or stay healthy.

“There’s about $25 billion being spent and incentives are a big part of that,” says Peter Mueller, a senior analyst at Forrester Research.

The $25 billion includes all the apps, devices, games and people devoted to helping us change longstanding, deeply ingrained bad habits.

“It’s really been the Holy Grail when it comes to changing behaviors, that’s where the industry falls short,” Mueller says. “We know a lot about what people need to do, but actually understanding the right triggers, that’s very difficult.”

Rewards like gift cards, a preferred parking spot or a certificate of recognition aren’t working. Enrollment in wellness or healthy rewards programs hovers around 20 percent. So more and more insurers and employers are turning to cash — albeit modest amounts so far, like Smith’s $20.

Or the $5 that nudges Ben Rubin out of his desk at the start-up Change Collective to the noon workout at CrossFit Southie, in Boston.

“There’s a bunch of warm-up, we did some strength tests beforehand, and then 15 minutes of basically hell,” says Rubin in a break between deadlifts, push-ups and squats with a medicine ball.

Dropping in and out of hell pays off.

“It helps me get stronger, helps me have more energy, helps me maintain a good weight and look good,” Rubin says.

And he takes $5 off his health insurance deductible for every 30-minute workout. Rubin has to be at a GPS-confirmed gym or connect through a device like Fitbit. If he does not exercise three times each week, Rubin will lose $5 for every workout he misses. That’s the pact Rubin signed, and offers his employees, through a company called Pact Health.

“By smartly adjusting the deductible based on exercise, we can save a small business tens of thousands of dollars a year in terms of their health costs,” says Pact Health co-founder and CEO Yifan Zhang.

Pact Health launched as an option for small businesses in Massachusetts that have some of the most expensive health care premiums in the country. Zhang says employers save money two ways: first, through increased exercise and the related health benefits; and second, by helping companies lower insurance payments. Plans with high deductibles are cheaper, but they shift costs to employees. Pact Health helps to offset the pain of higher deductibles.

“With Pact Health that’s one of the big benefits,” says Nick Francis, co-founder and CEO at the software start-up Help Scout. “You can go with a high-deductible plan and count on your employees kinda working down their deductible by using the product.”

Pact Health has had some glitches in monitoring movement using smartphones. But Francis says all the employees who get coverage through the company have enrolled.

(With Nutrisavings, insurers get information about how many people are using the program and how many members are hitting the 60 percent average, but Harvard Pilgrim doesn't see individual scores. With Pact Health, employers know who enrolls, but not how often employees meet or miss their pact goal.)

Francis says he exercises a little more than he used to, knowing that there’s some money at stake.

“I’ll definitely be incented to go on a run,” Francis says, “or I’ll be walking the dog and notice that I only [need] 2,000 more steps to get to 10,000 for the day, which counts as a workout.”

Zhang says many users increase the amount of time they spend exercising when they make a pact.

But there’s very little research that proves health incentives actually improve health.

“We’re not quite there yet,” says Gary Bennett, a professor of psychology, global health and medicine at Duke University. “While the early research in using incentives to promote more healthful behaviors is extremely encouraging, we haven’t seen the kind of larger durable changes that we really need to see to believe that incentives can promote longer term improvements in chronic disease rates."

Patients need to lose about 5 percent of their weight to improve their blood pressure, for example, and few health incentives show that kind of return. We’re in a period where insurers and companies are testing all kinds of strategies to encourage healthy living.

Soeren Mattke, a senior scientist at Rand Health, says more and more companies are penalizing workers who miss health targets.

“When we did our survey in 2012, we couldn’t even identify enough employers that did only penalties to study them. But it is changing,” Mattke says. “The penalty component is actually becoming more common.”

Pact Health members lose $5 when they miss workouts, but can make up that loss.

But, couldn’t you just cheat — go to the gym, log in, and then finish some work instead of working out? Or, going back to the grocery store, would some of us ring up the fruits and vegetables on the Harvard Pilgrim/Nutrisavings account and pay for the soda separately?

“You could game the system and get your $20, but the reality is, in order to know that you gamed the system, you had to know what you were buying. And so, right there, no matter how you look at it, there’s education happening,” says pasta sauce buyer Smith, who works for Harvard Pilgrim’s community foundation. Smith was committed to healthy eating before she signed up for this program, which Harvard Pilgrim calls EatRight Rewards.

So what about the shopper behind Smith who’s stocking up on soda and chips. Will $20 persuade her to swap some of the junk for a leafy green vegetable?

“If you’re eating chips today, I recommend you eat kale tomorrow, you’re never going to eat kale,” admits Niraj Jetly, the chief operating officer at Nutrisavings.

A more realistic goal, Jetly says, is to persuade the chip shopper to take one small step. How about baked or low-salt chips?

“If you’re eating these chips, try the other chips, which are a little healthier. Then give you a little bit nudge higher up. So it’s a gradual process to do the change of behavior,” Jetly says.

In Jetly’s Utopia, one person buying healthier chips turns into a trend. Then the produce section takes over the chips aisle. And while we look into the distant future, Jetly says it’s time to rethink the role of the supermarket.

“What we consume has got so much impact on the health and well-being, the supermarket should be part of the overall health care delivery system,” Jetly says.

And Zhang at Pact Health says employers may want to reward workers for other healthy behaviors, like sleep.

Getting paid to sleep? Nice.

Correction: An earlier version of this story inaccurately reported Sue Amsel's position. She's a senior product portfolio manager at Harvard Pilgrim. We regret the error.

This story aired on WBUR-FM on Feb. 17-18. Below are Parts 1 and 2.