Advertisement

Creating Arts Villages In The City — It Takes An Ecosystem

Uphams Corner isn’t a destination place for most arts mavens in Boston. It’s not Huntington Avenue, dubbed the Avenue of the Arts. It definitely isn’t Brattle Street with a string of high- and medium-end restaurants tending to patrons of the storied Brattle Theatre and American Repertory Theater.

So why on a gorgeous May day has an entourage that includes the head of the National Endowment for the Arts, the Barr Foundation, the Boston Foundation, the new Boston arts commissioner and members of the Massachusetts Cultural Council chosen this place to meet with artists and activists in a section of the city that is an expressway removed from the area's more famous arts centers?

The Barr Foundation and the Boston Foundation are the two philanthropic giants in the Boston arts scene and both have found much to celebrate in Uphams Corner.

There is the Strand Theatre, saved from oblivion by the Menino administration and now an important venue in the Walsh administration’s plans for engagement with the arts and neighborhoods. (Julie Burros, the arts commissioner, noted that the city in charge of the venue, but not as a programmer.)

It might not be apparent on a quick drive-through, but the Strand is hardly the only arts kid on the block. The Jose Matteo Ballet Theatre has opened a studio in the neighborhood and will have performances of “The Nutcracker” at the Strand this holiday season, as well as at the Cutler Majestic Theatre. And, just opened, the Fairmount Innovation Lab, a cross-disciplinary space for artists and entrepreneurs.

The Boston Foundation, along with ArtPlace America and the Kresge Foundation, has been a leading force behind the Fairmount Cultural Corridor Pilot, seeding, among other things, “random acts of culture,” installations, outdoor markets and complementary business activities."

“It’s very exciting,” said Paul Grogan, president and CEO of the Boston Foundation. “I’ve been involved in neighborhood revitalization in Boston and nationally going back to the White and Flynn administrations. I’ve seen Boston neighborhoods in very tough shape in terms of abandonment and blight. But I’ve never seen a revitalization effort that is employing so many elements simultaneously. Nor have I seen one that put arts in the center of efforts as this one has. It’s not a time to declare victory, but the effort that is under way, if it works, will have redevelopment implications in the city and beyond.”

There are a variety of organizations interested in urban development not only in Uphams Corner, but along the whole Fairmount corridor, which includes neighborhoods in Dorchester, Roxbury, Mattapan and Hyde Park, where the majority of children in Boston live and where poverty, unemployment and educational attainment have all been problems.

Advertisement

The Barr Foundation is a huge player in arts philanthropy. Cofounded by Amos and Barbara Hostetter, the foundation has established a more public profile. James Canales, its president for the past year, has been writing op-ed pieces, appearing at events the Barr has funded, partnering with Grogan and the Boston Foundation and, in fact, was sponsoring that daylong visit to Boston arts organizations by Jane Chu, the NEA chair.

Canales said that the visit was planned, in part, to show the improvements in the neighborhood brought about by ArtPlace, the foundations, local activists and the city, particularly “the quality of the nature of the collaboration, all organizations partnering and a broader goal aligning.”

Chu’s first stop at Uphams Corner was at the Fairmount Innovation Lab, down the street from the Strand at 584 Columbia Rd., shortly in advance of its recent opening. The two foundations and ArtPlace are among the lab’s supporters.

Walking up to the second floor of the lab, one is greeted with biographies of members and then, in the lab itself, by dramatic paintings and photographs by neighborhood artists such as Jaypix Belmer and Marlon Forrester.

This is not just an art gallery, but a space for would-be entrepreneurs looking to gain a foothold in crafts, preservation, advertising and marketing as well as in the arts. It’s seeking to build a synchronous relationship not only with the neighborhood, but with residents and businesses along the Fairmount Indigo Commuter Rail Line, which — thanks in large part to the Boston Foundation and community activists — now stops at Uphams Corner, Four Corners/Geneva Avenue, Talbot Avenue, Morton Street and Blue Hill Avenue Cummins Highway. One of the speakers joked to the assemblage how the mostly black and brown residents of Uphams Corner would be crowded together into buses while watching the mostly white commuters whiz by comfortably on the rail line.

Two of the community activists, Harry Smith and Lori Lobenstine, had earlier taken Chu et al on a walking tour of the Uphams Corner neighborhood, pointing out steps that had been taken to connect the dots with transportation, safety (how a lighted bridge made a huge difference along the rail line) and attempts to keep neighborhood housing for the local residents.

Chu said this was about her 50th such visit in 10 ½ months on the job. “When you’ve seen one community you’ve only seen one community,” she told us later, and seemed genuinely impressed by “the momentum and vitality” of the area.

So what’s art got to do with it? The NEA has been a leading advocate for “creative placemaking.” It’s kind of “broken windows” in reverse. Chu talks about how you see one person sweeping the steps and soon everyone is. She was preaching to the converted, among the foundations and community artists and activists, but it was still a sermon they were appreciative to hear.

By extension, artists begin adding vibrancy to a neighborhood, giving a jump-start to a neighborhood’s sense of self. Restaurants and other businesses follow, housing is developed, empowered residents seek more improvements, artists and residents develop a kinship amid the mutual interest.

Life doesn’t always follow the script, though. Arts organizations go out of business or move to a place where there are bigger audiences. Restaurants struggle when there aren’t performances (even along the Avenue of the Arts on Huntington Ave.) Gentrification and high rents force out the artists who helped make it desirable in the first place. Not to mention working-class residents who see their rents become unaffordable.

Even with the Strand, the Fairmount Innovation Lab, the commuter rail, new housing going up, Uphams Corner doesn’t look like it’s ready to explode. Which is perhaps what has drawn all these forces together. Chu talks about how “It takes a long time for things to happen suddenly.”

Lower Washington Street is a case in point, albeit at the other end of the economic spectrum from Uphams Corner. Nevertheless, calling that end of Washington Street an eyesore would have been an understatement 10 or so years ago.

Look at it now. Public safety is no longer much of an issue. Thanks to a great deal of help from the Menino administration the Opera House was restored in 2004, followed by the Paramount Center and Modern Theatre. Luxury hotels and condominiums sprang up. Good restaurants proliferated.

Chu’s next stop was to the Paramount Center where ArtsEmerson artistic director David Dower spoke about the organization’s “commitment to working in the gaps,” including bringing African-American, Latino-American and Asian-American artists and audiences to the theater and “putting as many cultures as possible onstage.” And onscreen, as ArtsEmerson is one of the hosts of the Boston Asian American Film Festival in AE’s varied cinematic program.

It would be wrong to say that ArtsEmerson and Broadway in Boston, which runs the Opera House, are responsible for the wholesale change. But, says Dower, “My sense is that ArtsEmerson and the Opera House have given the neighborhood and its development a defining sense of character. The development was going to happen, particularly once Emerson and Suffolk moved there. But the distinctive vibe there these days is emanating from the presence of the arts and students.”

It’s easier to do this in downtown Boston, of course, than Uphams Corner, but it’s obvious that the city, foundations, artists, activists and residents have a synchronous relationship in Dorchester. Harry Smith, director of sustainable economic development at the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative, mentioned 80 new affordable homes being constructed across the street from the Strand and 225 homes that have been built on a community land trust.

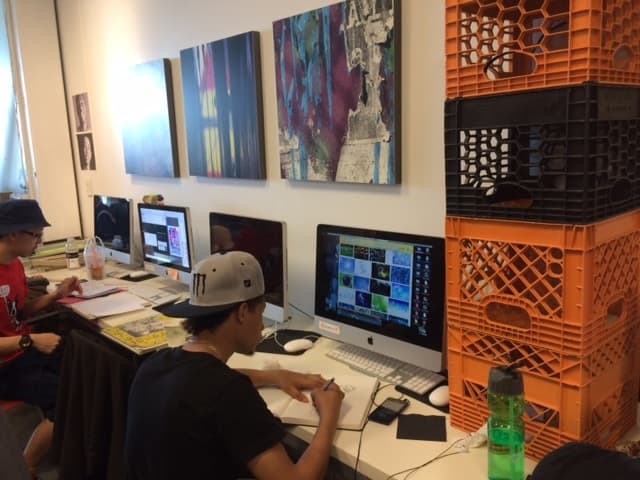

From the Paramount, Chu went on to the Artists for Humanity Epicenter, a bustling, boxy building not far from the Fort Point studios where she saw local artists doing photo shoots, making T-shirts, assembling video art and collages and working in other idioms. The center’s mission is “to bridge economic, racial and social divisions by providing underserved youth with the keys to self-sufficiency through paid employment in the arts.”

While the building’s wall lists contributions from foundations and individual patrons, executive/artistic director Susan Rodgerson takes pride in saying that, “We employ 250 plus teen artists annually and earn 45 percent of our total organizational budget from the sale of fine art and creative services.” She adds that the program is open to young people, mostly from Boston, aged 14 to 18, and is the largest employer of Boston public students in the city.

At a later reception for past NEA grant winners at Artists for Humanity, Anita Walker, executive director of the Mass. Cultural Council, talked about the MCC, NEA and Artists for Humanity “serving the most vulnerable young people” and how the arts can lead them to positive answers to the questions, “Do I matter?” and “Can I make a difference?”

Chu seemed particularly energized by the grassroots activities in the arts she witnessed but emphasized in a separate interview that the NEA takes great care in spreading its wealth, so to speak, among large, small and midsize organizations, as does the MCC, and the Barr and Boston foundations. Representatives of local organizations seconded the notion of fairness up and down the spectrum.

Chu, Canales and Grogan all mentioned variations of “ecosystems” in which a healthy arts community needs strong large, midsize and small organizations. One can even extend that to situations where larger institutions like ArtsEmerson and the Huntington Theatre Company have helped smaller groups like Company One Theatre or how the American Repertory Theater’s Club Oberon has hosted a variety of small music and theater groups.

The grassroots part of the “ecosystem” isn’t one that a lot of arts patrons usually see. People in various professions often say, “You don’t want to see how the sausage is made.” But for Chu and her Boston entourage the day was as illuminating as seeing a high-class performance onstage.

“We still have a problem in Massachusetts seeing arts as a frill,” said the Boston Foundation’s Grogan. “When money’s a little tight people say we’ll forego spending money on the arts. And that is so wrong. What we see is that the arts speaks to both the human spirit and economic development.”

Ed Siegel is editor and critic at large for The ARTery.