Advertisement

The Many Revolutions Of Miles Davis At Newport

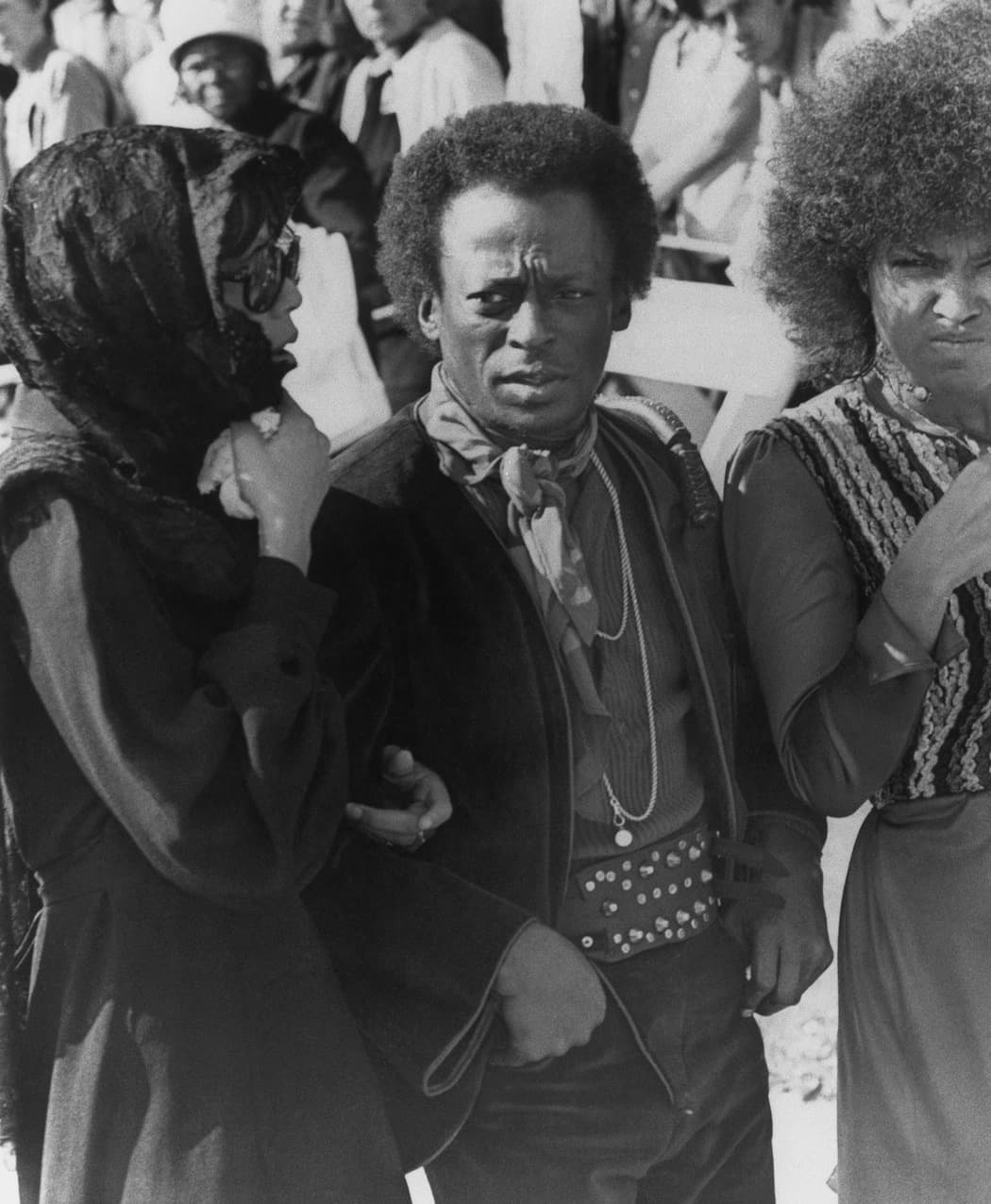

Has there been a more exciting figure in the history of jazz than Miles Davis? Not the greatest musician, certainly, or the best ambassador for the genre, but the one who took the bop mantle from Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie and then did things that no other jazz artist could have dreamed of.

That excitement has been bottled to near perfection in Volume 4 of Columbia/Legacy’s Bootleg Series: “Miles Davis at Newport 1955-1975,” with the trumpeter surrounded by a musician or two you might have heard of: Thelonius Monk, Gerry Mulligan, Zoot Sims, John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans, Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Tony Williams, Chick Corea, Dave Holland, Jack DeJohnette, Keith Jarrett and James Mtume Forman.

This is not, though, a collection of all-star jazz riffs. Nor is it the way to introduce the unitiated to Davis, with all of its tubro-charged explosions into the next incarnation. For most people entry into the cult of Miles is a gradual process. Maybe “Kind of Blue” was the gateway drug or “Porgy and Bess.” “Sketches of Spain,” perhaps. From there moving back and forth in time with Miles has been a lifelong excursion into the heart and soul — and let’s not forget the mind — of the unique artist. Listening to Davis can be as much a cerebral experience as an emotional one.

“The Essential Miles Davis,” a two-CD set also on Columbia/Legacy is the best one-stop shopping buy to get at the complete Davis in the studio, but this provides the most compelling evidence for the raw excitement of Davis in concert.

It’s fitting that the compilation begins with an introduction by Duke Ellington. The first half of the first CD is, in fact, an all-star 1955 set, with Davis joining Monk, Sims, Percy Heath and Connie Kay. “These gentlemen live in the realm that Buck Rogers is trying to reach,” says Ellington. Is it a sly putdown that they’re too far out or a confession that they’ve left Ellington behind? (Let’s not forget, though, that a year later it was Ellington who stood Newport on its head.)

Mulligan had played McCartney to Davis’s Lennon on “The Birth of the Cool” seven years earlier and the 1955 set still envelops you in that warm bath of coolness. But since these numbers were written by Monk and Charlie Parker, there’s an edge to the compositions that match up nicely with the professionalism of the playing. Percy Heath and Connie Kay stay in the background, leaving the star turns to the others.

There’s nothing cool, though, about the flamethrowing burst of “Ah-Leu-Cha,” leading off the 1958 set. And the rhythm section comes out of the background with Jimmy Cobb’s drumming freed from merely keeping rhythm. Just listening to the saxes, the leap from Mulligan and Simms to John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley is even more profound than the next leap to Wayne Shorter. Bill Evans settles things down, but the energy level makes it clear this isn’t “Kind of Blue” live.

Each of the sets, really, begins with a new burst of energy as if Davis is announcing an artistic rebirth from the first number. In all but the last set, his trumpet playing takes on a ferocious power, not only matching the vitality of the new members, but leading them forward.

The second CD showcases the second great quintet and the confidence level is jaw-dropping, particularly when they take the classic “All Blues” and turn it inside out even as they maintain a foothold in Miles’ past. Tony Williams’s drumming is even more assertive than Jimmy Cobb’s. And if Bill Evans is holding back a bit in ’58 Herbie Hancock is pushing forward with power and precision, though providing more of a melodic base to the proceedings. A year later, Wayne Shorter gets more assertive on sax, even outré. Where could Davis go after this configuration?

The answer would be further and further away from his roots and more into electronics. Even with the switch away from acoustic keyboards and bass, and despite Davis’s growing interest in Jimi Hendrix and rock music — Newport festival producer George Wein has interesting things to say about that in the liner notes — the “Bitches Brew” sessions on the third (1969) and fourth (1971) sessions never feel like they’re not jazz. Particularly when you consider who his two keyboard men are — Chick Corea and Keith Jarrett. Corea seems more at home in the smaller ’69 group, but it’s still fascinating to hear foreshadowings of Jarrett’s bluesy classicism in the larger group.

The 1975 set delves even further into funk and electronics. You even have to pay attention at times to figure out whether it’s the guitar or trumpet playing. You can isolate any of Davis’s sidemen to pinpoint Davis’s various stages. Saxophone would be the most obvious, but I was particularly struck by the drumming changes from group to group — from Connie Kay to Jimmy Cobb to Tony Williams to Jack DeJohnette to Mtume on percussion with various drummers. Each is a hall of famer and each seems to be driving Davis and the others to those newer energy levels.

Advertisement

Not all the concerts are in Newport. Wein tried repackaging that magic in Europe and in Avery Fisher Hall. But wherever he’s playing, Davis is laying down the gauntlet to fans, critics and fellow musicians. And listening to these four CDs, it’s no wonder so many followed him.

Ed Siegel is the editor and critic at large of The ARTery.