Advertisement

Everett Families, Doctors And First Responders Work To Combat Spike In Overdose Deaths

Patti Scalesse says she never saw it coming. Even when she found a syringe cap in her car three years ago and called her son, Francis Kenney, to tell him not to let his friends get high in her car. When Kenney then told her they needed to talk, Scalesse never expected to hear that her boy was addicted to heroin.

"Not my kid, my kid would never use drugs, he was a Marine," Scalesse remembers thinking. "Well guess what, he did."

Kenney, then age 21, was discharged from the Marines with a prescription for pain medication. Within a year of his release, Scalesse says, he had switched to heroin and was asking her for help.

"I thought, OK, I’ll pack him a bag, give him a pillow, bring him to detox, five days later he’ll be home and everything will be OK. No one tells you that the next two to three years of your life is just pure chaos."

Patti Scalesse, speaking about her son's battle with addiction

They met in a park, down the street from a pizza joint where Scalesse learned her son routinely went into the bathroom to get high. Scalesse absorbed the shock and started figuring out how to fix the problem.

"I thought, OK, I’ll pack him a bag, give him a pillow, bring him to detox, five days later he’ll be home and everything will be OK," she says with a dry laugh. "No one tells you that the next two to three years of your life is just pure chaos."

Chaos, because Kenney relapsed several times, and Scalesse realized she didn’t know what to do.

"I went to the police station and city hall to see what sort of information I could get to get my son some help. Nobody had anything. They gave me a 1-800 number with a Post-it note," Scalesse says.

So she started a group, Everett Overcoming Addiction, that brings together parents and patients who are learning to manage this chronic illness. Her son, now 24, spoke at a rally. Kenney has been off heroin for 10 months and has a job. But as Scalesse was building a website, planning events and reaching out to other families, the disease hit her family again.

Advertisement

"My nephew was just 17," Scalesse says, sighing. "We did not know he was using, and we got the call that he had died."

'Nothing Surprises Us Anymore'

That was on April 10, not quite four months ago. Scalesse says by the time someone found her nephew there was no point taking him to Whidden Hospital in Everett, where Dr. Melisa Lai Becker says overdose patients have become way too common.

"We are seeing someone probably every day, at least one patient a day," she says.

Whidden has 50,000 emergency room visits a year, many of which come from outside Everett, where the population is about 43,000.

Lai Becker says there’s no typical substance abuse disorder patient. A mix of men and women come in on stretchers ranging in age from 17 to 79.

"Nothing surprises us anymore," Lai Becker says.

The Whidden team saves the vast majority of these patients, but not all. Last month, on a beautiful Saturday, two different ambulances phoned in a "Code Blue" warning within minutes of each other. Two patients, one man and one woman in their 30s or 40s, had overdosed on heroin, were not breathing and did not have a pulse.

"Both were resuscitated right here in this room," Lai Becker says, gesturing to a room lined with medical equipment. The families of both patients, including young children, streamed in as doctors and nurses rushed in and out of the glass double doors.

"Our chaplain was here. Our social worker was here. Both of the patients died. It was emotionally overwhelming," Lai Becker recalls.

She marvels at the maturity of teenagers who drive to the emergency room behind an ambulance carrying their parent, trying to calm a younger sibling who found the mother or father unresponsive.

Lai Becker worries too about the safety and emotional well-being of her staff. Reversing a heroin overdose might save a patient’s life, but they may come back to life vomiting, in pain, swearing and angry, demanding to leave.

"You never know, you might resuscitate someone into punching your nurse," Lai Becker says.

Is there any other type of patient who comes in near death, the staff saves their life, and they are angry rather than grateful?

Lai Becker looks up at the ceiling for a minute before answering.

"No," she says shaking her head, which reinforces the power of this addiction and disease.

Working To Break The Cycle

Whidden and two other emergency rooms that are part of Cambridge Health Alliance are trying to prevent addiction to opioids by limiting pain medication prescriptions to a three to five day supply. Lai Becker says the vast majority of opioid prescriptions come from other specialists. Emergency room doctors and nurses deal with the end results and try to guide patients to recovery, but often aren't successful.

"We want to help break the cycle," Lai Becker says. "We have social work, we have case management, we have very concerned, very compassionate staff. The patient, you hope, has just had a life changing event, and you’re hoping that they will not tear up the discharge instructions that you just prepared and went over with them. A lot of times, people don’t want to talk to us."

Lai Becker says too many patients who do seek help can’t find detox programs that specialize in opioid abuse or counselors to help them manage the disease. Many are told they'll have to wait days, weeks or months for treatment. Those who can’t wait, and hit the street to buy more heroin, may encounter Everett Police Detective Robert Hall.

“Maybe that’s what has to change. Maybe traditional public safety agencies now have to fall into the realm of social services too."

Everett Fire Department Capt. Anthony O’Brien

On this day, Hall steers a red unmarked Honda, confiscated from a drug dealer, past modest, well-kept houses.

"I’ve done many, many drug investigations on this very street," Hall says. "It’s a nice little neighborhood, lot of single family homes, multi-family homes, there’s some businesses down here on the parkway."

Hall, who works undercover, pulls into a parking lot behind a strip of stores.

"It’s just a central meeting spot off of a major highway," he says, putting the car in park and glancing around. "People come from Somerville, they come from Everett, they come from Chelsea. Some, as soon as they get the drug, they want to use it. So they find the closest bathroom — a Dunkin Donuts, a Burger King, a McDonald’s, a Taco Bell — and you’ll have an overdose."

Everett may see even more overdoses and deaths this year than the 23 tallied by the state in 2014. That number, based on the residence of the deceased, is already more than four times higher than the five overdose deaths recorded for Everett in 2013.

Hall says he can't explain the spike. Maybe it was the increase in fentanyl — a highly potent narcotic that is sometimes added to a batch of heroin. Maybe it was the harsh winter, "where people couldn’t get to the clinics, so they can’t get their methadone, so they’re going to use. Depression sets in."

Hall wants to be clear: He is not a doctor. But he has met hundreds of people addicted to heroin, many of whom seem to be using the drug to numb emotional pain.

"[I see] victims of PTSD, victims of sexual assault, victims of child abuse — people that need prevention earlier," Hall says. "They need to go and talk to professionals so that they can cope, so they don’t go to prescription pills and then to heroin or cocaine or whatever the drug is."

Some first responders in the Everett Fire Department agree.

"If you want to tackle drug issues you have to tackle mental health issues," says Everett Fire Department Capt. Anthony O’Brien."Until we resolve ourselves, saying that's what we want to do, then you're kind of wasting your time."

But if mental health problems are the main issue for many Everett residents who struggle with opioids, what's the fire department's role in tackling the epidemic?

"It's evolving," O'Brien says. "Traditionally the fire department’s not a warm and fuzzy agency. We respond, take care of a problem and come back."

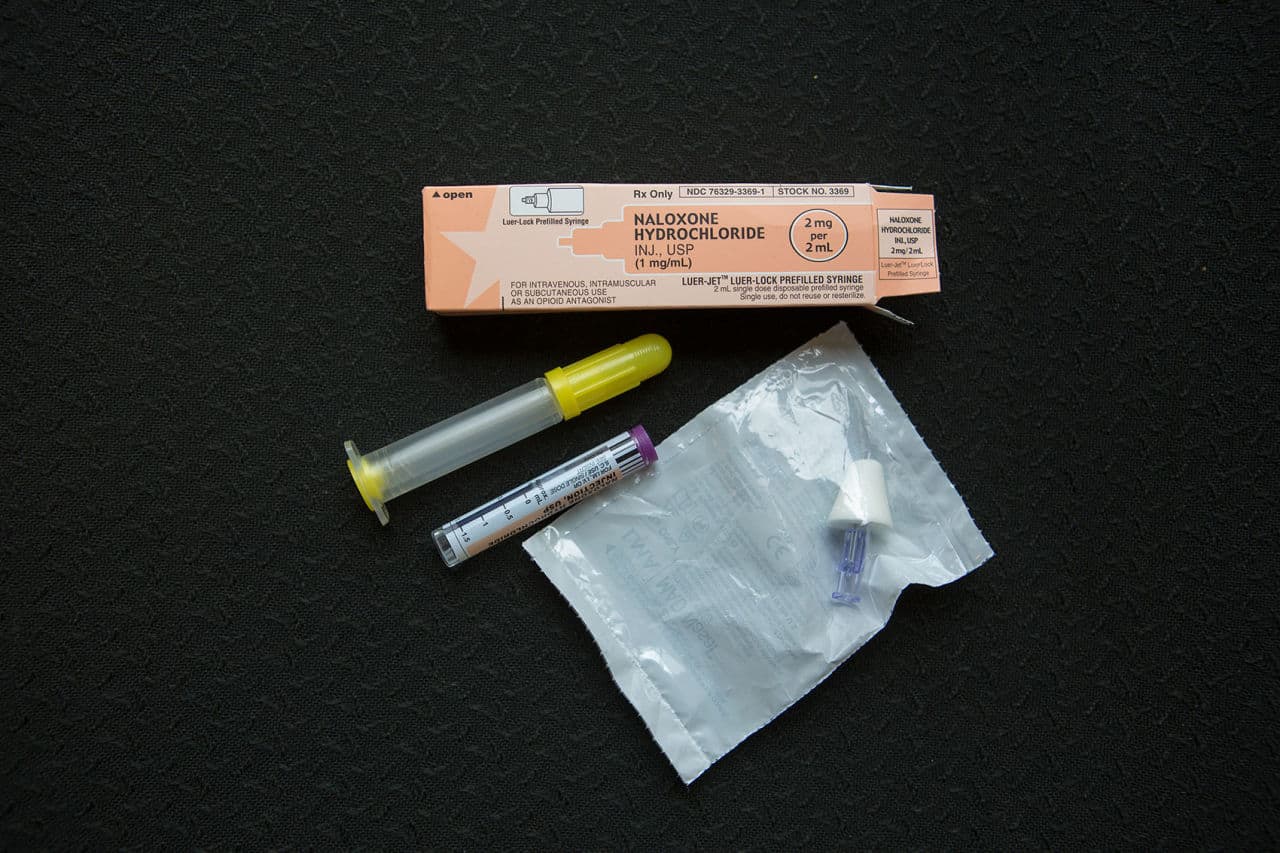

Facing an opioid epidemic, Everett firefighters decided to start carrying naloxone, a drug that reverses the effects of an overdose. They purchased an initial supply and trained the staff.

"It was solely because the guys, the department recognized the importance of it," O'Brien says.

Everett firefighters have used naloxone to revive 21 patients since December. One person did not recover from the overdose and died. Everett police are not equipped with naloxone, although that may be changing soon.

This fall, firefighters will hold workshops at the public library for anyone who wants to learn how to administer naloxone and perform CPR on a patient who has overdosed. O’Brien says Everett is not yet following firefighters in Revere, who return to homes where there was an overdose to check on the person and hand out information about getting treatment.

"Maybe that’s what has to change," OBrien says. "Maybe traditional public safety agencies now have to fall into the realm of social services too. I don’t know if that’s the best answer, I don’t think it is, but maybe that’s what has to happen."

'Progress Has Been Made'

At the Everett Family Health Center, Dr. David Roll says it’s important to remember that patients addicted to heroin or opioid pain medications can learn to manage the disease.

"And when they do, it’s really amazing what an enormous transformation it makes in their lives," Roll says.

He describes patients who've lost everything and are living on the street, but regain their health, get a job, an apartment and in a few cases regain custody of a child.

Roll says doctors at his center and his network, the Cambridge Health Alliance, are making questions about illegal drug use part of the annual physical. They’re treating substance abuse disorder with frequent calls and check-ups, as they do diabetes, asthma or other chronic diseases.

“Progress has been made,” says Jean Granick, who runs the Everett Community Health Partnership’s Substance Abuse Coalition, a project of the Cambridge Health Alliance. “I don’t think anyone is giving up.”

The opioid epidemic is becoming an issue in the Everett City Council race.

"It's time to tackle this head on," says candidate for Ward 3, Anthony Dipierro, who is calling for city-funded substance abuse counselors and more government funding of treatment beds. Dipierro says Everett should take a close look at Gloucester, where police are moving away from arresting heroin users and instead trying to direct them to help.

But even with help, "it’s one day at a time, you don’t know what today’s going to bring," says Scalesse, whose son is in recovery.

Will her son stay healthy and off heroin? And what kind of danger does her bubbly blond granddaughter face?

"I have his daughter, I’m raising her. Her parents are addicts, you have to try to break that cycle, you have to," Scalesse says, pausing. "How am I going to protect her?

It’s a question many families in Everett and across Massachusetts are asking themselves as they learn that, on average, nearly four residents are dying every day of an unintentional heroin or prescription pill overdose.