Advertisement

ICA Explores How The Avant-Garde Thrived At Black Mountain College

It's pretty mind-blowing to take in the who’s who list of luminaries who passed through Black Mountain College between 1933 and 1957.

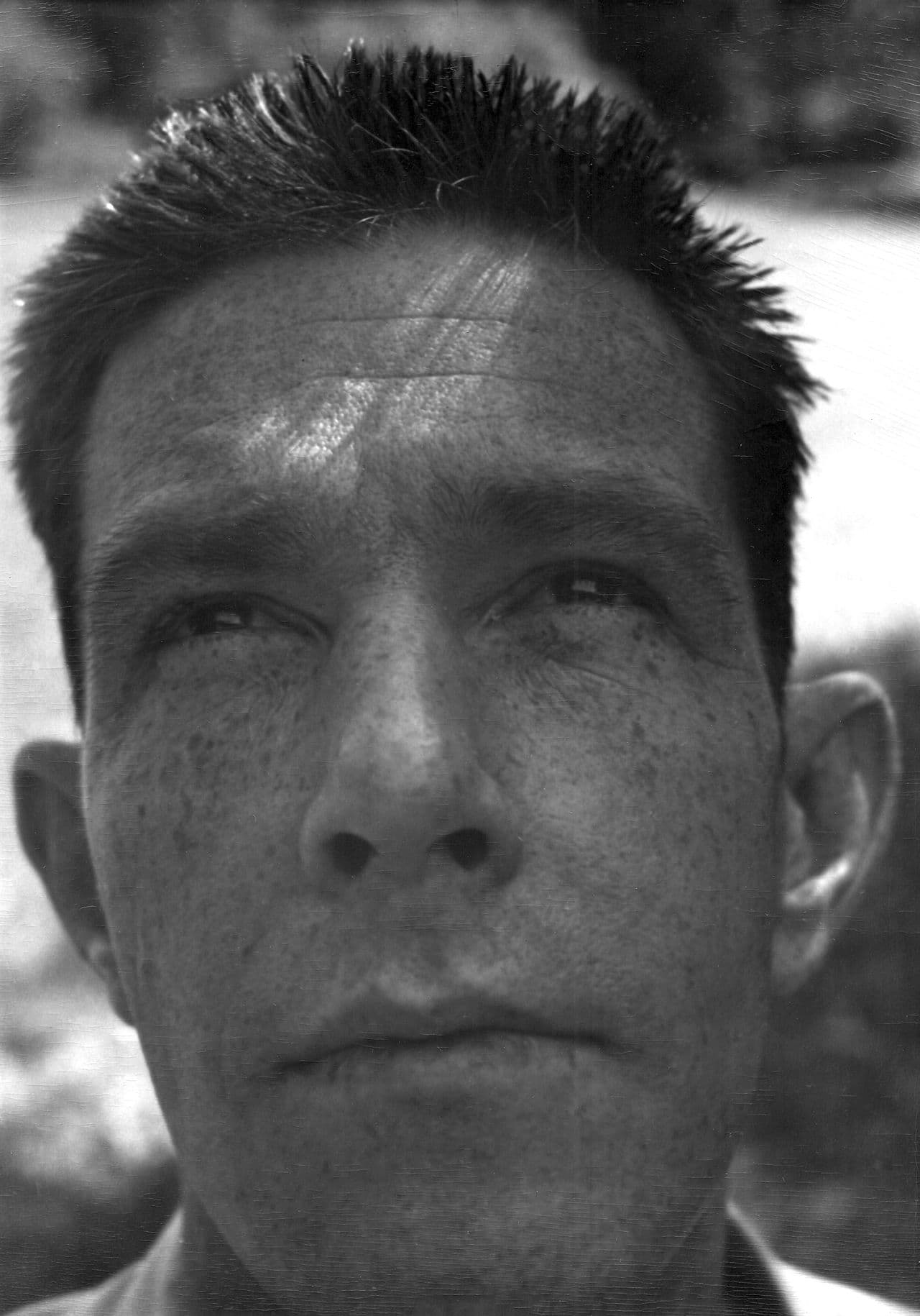

Composer John Cage is one of them. He premiered "Sonata V" from his groundbreaking "Sonatas and Interludes" at the school in 1948.

"I’ve really come to see Black Mountain as the wellspring of the American avant-garde," says Helen Molesworth, who curated the Institute of Contemporary Art's new exhibition on the school. "Cy Twombly to Robert Creeley and Charles Olson and Robert Motherwell, and Merce Cunningham and John Cage." The list goes on.

Molesworth has collected 261 objects by about 100 artists for the new exhibition, titled "Leap Before You Look." The collection, which includes archival materials and live performances, tells the story behind Black Mountain College, a small but legendary liberal arts school.

"It happens because of a crisis," Molesworth says, explaining how the school came to be. "A tenured professor is fired because of his radical ideas."

That professor was John Andrew Rice. When he left Rollins College in Florida some of his students and fellow faculty members followed. They decided to create their own institute of higher learning in the secluded mountains of North Carolina, on the grounds of Christian summer camp.

"And they decided that the college would be founded on the principles of progressive education," Molesworth says.

They were inspired by philosopher John Dewey's belief in “learning by doing.” They also decided Black Mountain would have no trustees or board of regents. Instead, they would run every aspect of the school themselves — right down to growing their own food and designing their own buildings.

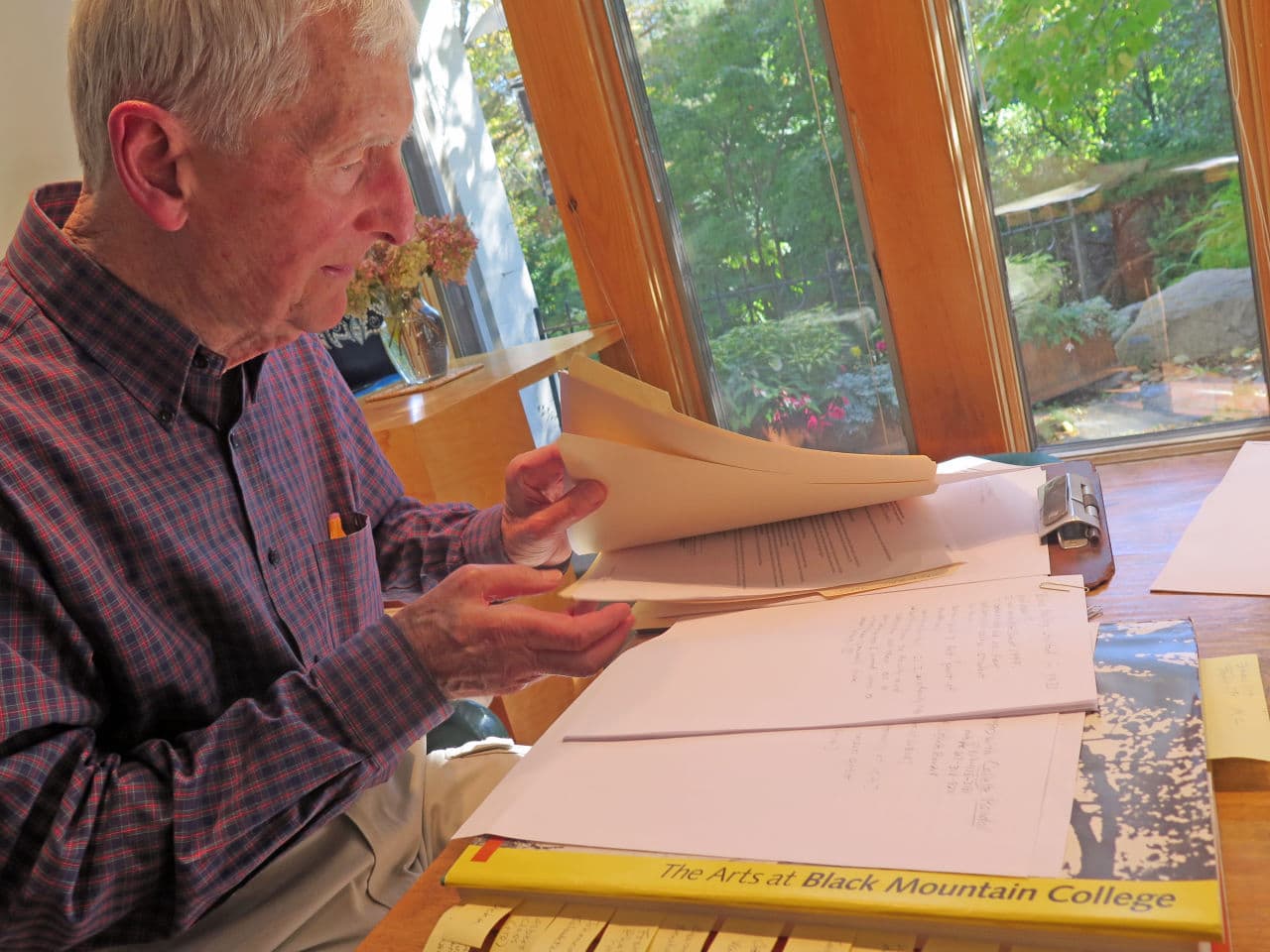

"The idea was to have somehow freedom to choose, but to be a community and to share," remembers 86-year-old Ted Dreier. His father, mathematician Theodore Dreier, was a founding faculty member. "And there was really a principle that was soon adopted that art should be given equal priority to the other courses, and that was great."

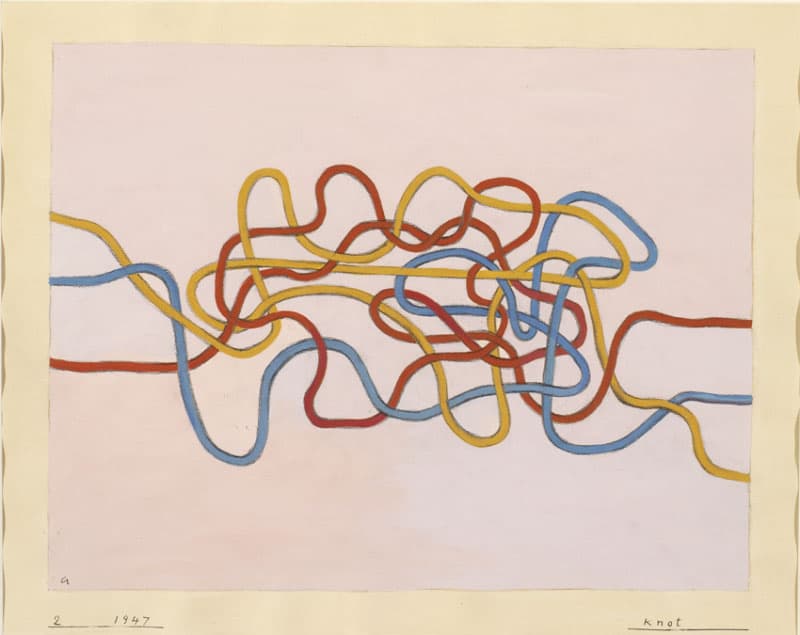

And it was also revolutionary. In the 1930s and '40s, Black Mountain attracted artistic, intellectual refugees who were forced to flee Nazi Europe, including Josef Albers of the Bauhaus school and his artist wife, Anni.

Dreier was only 4 years old when his parents brought him to Black Mountain, and he says he grew up surrounded by free-thinking “doers” who engaged in everything from high-level math and science to architecture, painting, pottery, weaving, sculpture, music and poetry — which Dreier still writes today.

Sitting in his Belmont kitchen, the former McLean Hospital psychiatrist shares one about his dance teacher:

Merce Cunningham

shows

right arm up

left arm

out to the side

says

Shoulders down, Ted…good,

Now

One-two-three-four-five-

Six-seven

Pause

One-two-three-four-five

Still

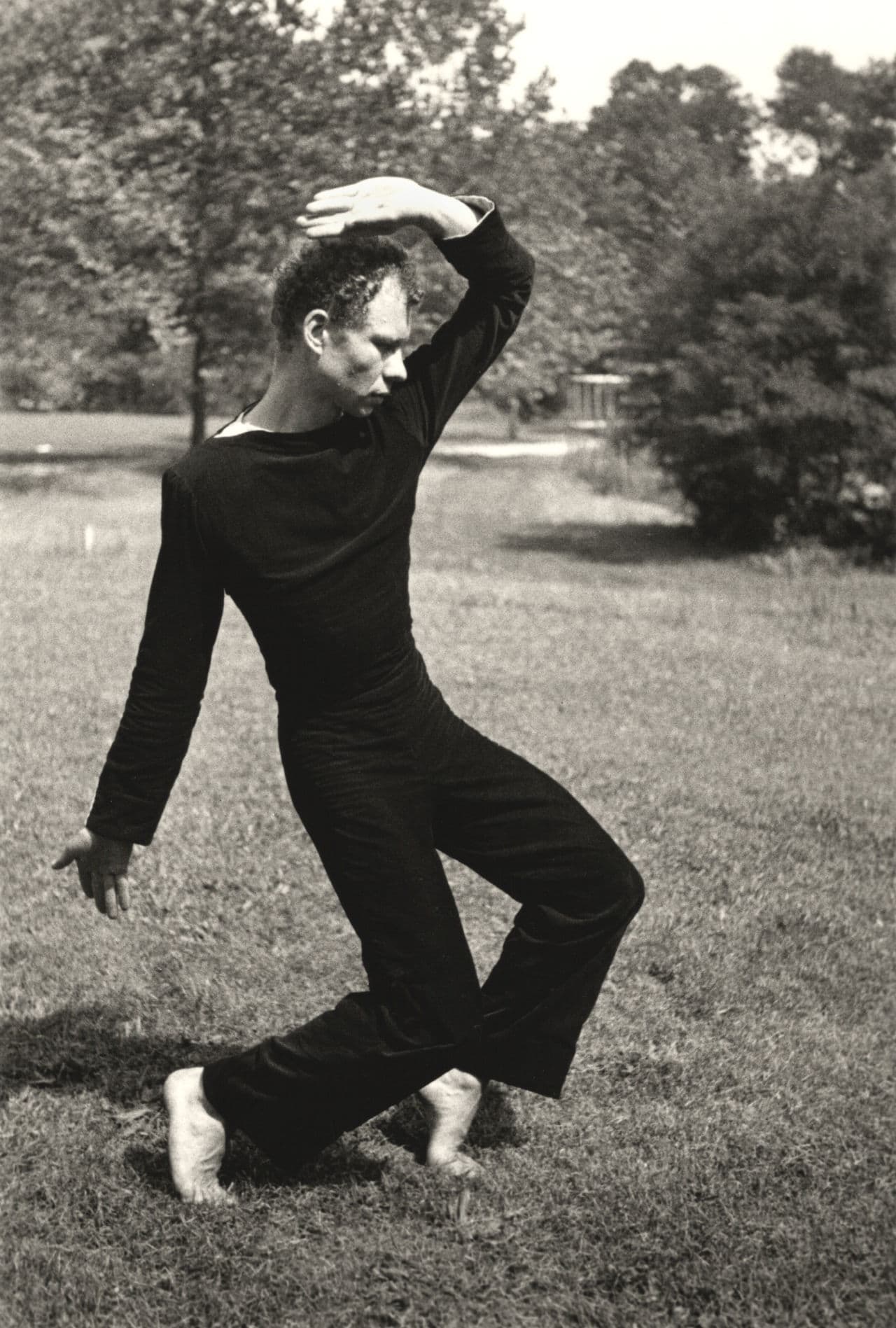

Merce Cunningham formed his famous dance troupe at Black Mountain. As part of the ICA exhibition, former Cunningham company dancer Silas Riener has been teaching Boston Conservatory and Harvard students pieces his mentor created at the school.

In November, Riener will perform a Cunningham work called “Changeling” — which was lost for half a century before footage of it was discovered in a German TV archive.

Riener says the work Cunningham and his frequent collaborator John Cage conjured at Black Mountain was radical for dismantling ideas that came before. One of the concepts they both toyed with was something called, "chance procedures."

"He would divide the space up into six partitions and he would roll dice to see who would be in what space," Riener says. "Or he would roll dice to see what order the dance would go in. Or he would flip coins or roll dice to decide what movements a person might do."

Black Mountain was like a laboratory where everyone was experimenting. Inventor Buckminster Fuller erected his first geodesic dome there in the summer of ’48.

"It was a huge failure. It didn’t stand up," Molesworth, the ICA curator, says. "They ended up calling it the 'Supine Dome' as a joke. The next summer, in 1949, he came back and this time they got it right. Failure is something that was cherished, in a way, at Black Mountain."

Abstract artist Dorothea Rockburne, now 83, started out at Black Mountain in 1950 with people like Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly. Today you can find her work at institutions like the Museum of Modern Art.

"Everything that I do relates back to Black Mountain in some way," she says, laughing.

Rockburne says she connected deeply with her teachers, including mathematician Max Dehn and poet Charles Olson.

"They certainly gave me the tools to lead my life with excitement and enthusiasm, because being an artist is a very lonely pursuit," Rockburne said. "So to have the tools that Black Mountain gave me allowed me to be an individual knowing what to do next."

The experiment at Black Mountain eventually came to an end in 1957 when the school ran out of money. The poets moved to San Francisco to join the beats, Molesworth says, and the painters found a vibrant contemporary art scene in New York.

"I think like many experimental, avant-garde places it had a lifespan," Molesworth says. "If anything when people say to me, ‘Oh, I wish it were still there,’ I always say to them, ‘You should make your own.’ "

ICA Boston's exhibit "Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957" is on display from Oct. 10 to Jan. 24, 2016.