Advertisement

'Stick Around One More Day': Message Of Hope After Medford Man's Suicide

For Marlin Collingwood, Monday, May 5, 2014, started on a high note.

"It was a gorgeous day — a beautiful, perfect, New England May, early day in spring," Collingwood recalls.

Collingwood's husband, 45-year-old Gary Girton — who had been battling severe clinical depression for several years — had seemed happy the night before. The two had made dinner together and watched a movie.

But now, with Girton not answering the phone or responding to text messages, Collingwood drove home to Medford from his Boston office to check on his husband. And it became the day he had feared with the deepest of dread.

"As I was pulling down the street where we lived, I could see our front porch and there was note taped to the front door," Collingwood says. "And it said, 'Marlin, I've taken my own life. I don't want you to find me. Call 911 and then call Molly. I love you, Gary.'"

Molly Baskette is Collingwood and Girton's pastor. She'll never forget the phone call she received from Collingwood that day.

"There was just Marlin screaming, crying on the other end of the line. He said, '[Gary's] gone. He's gone Molly, he's gone, he's gone.' That's all he could say. And I said, 'I'm coming right over.' And I just held him, and he wept and he raged."

Baskette eventually went inside the house, where police had confirmed Girton was dead.

"Molly spent time with his body and anointed him, and prayed for him," Collingwood recounts. "And I was adamant based on the way he had courageously fought this disease that we were not going to hide the fact that he had taken his own life."

That started with Girton's funeral at First Church Somerville.

"People need to know that we can have a conversation about this, that we have to," Collingwood reflects. "People are dying every day. And the church and faith communities have to be able to reconcile that this is happening to people in their own communities."

Talking Openly About Mental Illness And Suicide

Girton and Collingwood had gotten their whole church talking about mental illness. Girton wasn't religious, but he was open-minded and enjoyed the congregational church community, his husband and pastor say. He spoke about his depression multiple times at Sunday services.

"He talked about how he saw God present in his very skilled psychotherapist or [in] the love, the healing love of this community," Baskette says. "And a lot of people were helped by him having the courage to share that story."

Collingwood says his husband would actually tell anyone who would listen — even strangers — about his mental illness and hospitalizations. He hoped to learn something new that might help him, and to shatter stigma.

"If somebody said to him, 'How are you?' He didn't say, 'I'm fine,' like most of us did. He said, 'You know what? I'm really struggling today, and here's what's going on. And I was in the hospital three weeks ago.' He hated, hated when people would say to him, 'You just need to pull yourself up by your boot straps. You just need to go take a walk,'" Collingwood explains.

Advertisement

The World Became Dark

Girton had suffered from depression since before he and Collingwood met in Pittsburgh in 1998. He kept it under control with medication for years, but he remained a "glass-half-empty" kind of guy, his husband says.

The two moved to the Boston area in 2003, just months before same-sex marriage was legalized. They married less than two years later, surrounded by family and friends on the beach in Provincetown. Educated as a teacher, Girton was working as an actor and mosaic artist.

"He loved kids. He loved to help kids learn to read," Collingwood says. "And he was just the kind of person who would help you, who wanted to see a better place in the world for everyone, very committed to equality."

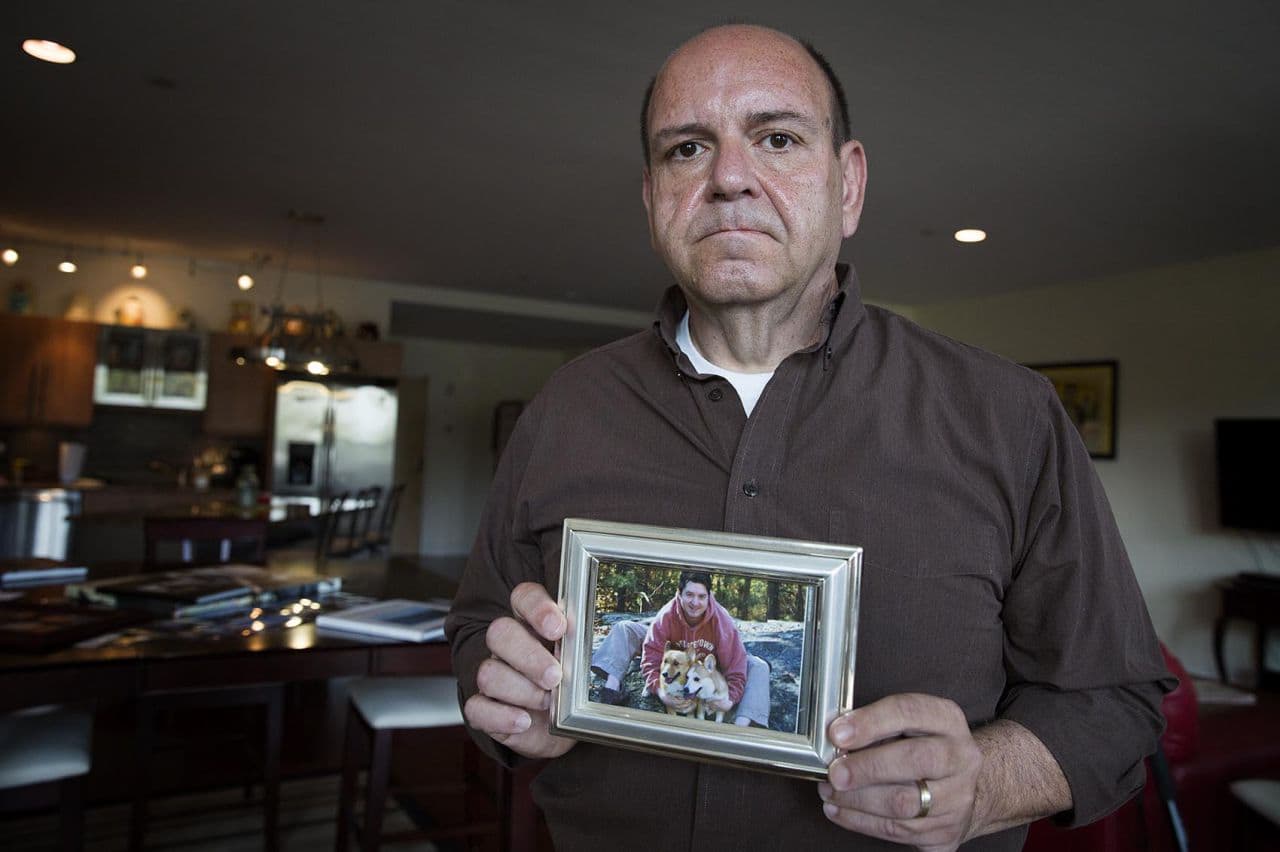

And he loved the couple's corgis, Harry and Torre. Collingwood points to a picture of Girton with the two dogs — a picture in which he is smiling — which was used at his memorial service. It's Collingwood's favorite.

The smile in the picture wasn't a regular sight on Girton's face. But he was leading a productive life — at least, that is, until 2011. Just after Girton recovered from a bad stomach virus, his depression became severe. Suddenly, as if a switch had been flipped, he told his husband the world had become dark. And it just got darker.

Girton was hospitalized at McLean Hospital multiple times, including once when Collingwood discovered some pills he had bought on the Internet to kill himself. He tried every therapy and medication psychologists and psychiatrists recommended, his husband says. He went out into the community to help others — tutoring homeless children in a shelter and feeding the homeless on Boston Common — as a form of therapy. Collingwood acted as Girton's caregiver and advocate, making daily calls to doctors and going with him to his appointments.

"He did everything he was told. He was told exercise, and some mornings he would get up and he would get on the elliptical, and he would be crying because he did not want to do it," Collingwood recalls. "He wanted to just go to bed. He would get up and he'd take a shower, and he'd get dressed and he would go to to work. And it was torture for him for a long time."

Baskette recalls some of what she said to Girton when he discussed his suicidal thoughts with her: "We want you here. We want you here for your own sake, because I believe if you stay, you will come through this time. And you will be able to enjoy life again. And God has so much more in store for you here. And we want you here for our sake, because we love you, and because suicide leaves a terrible exit wound."

Electroconvulsive Therapy Brings Glimmer Of Hope — For A Time

With all other treatments failing, doctors at McLean recommended ECT — electroconvulsive therapy. Girton was hesitant because of frightening images he had seen from movies and knowing it would likely cause some memory loss.

But he started the shock therapy and would feel a bit better for a few days, then tell his husband he wasn't getting better. Still, it was enough to give him a little hope, Collingwood says, and that's all he wanted.

Then in November 2013, Girton experienced something that almost never happens with ECT. He went into cardiac arrest during the procedure. He was rushed to another hospital and revived, but wished he hadn't been.

"His first reaction was, 'You should have just let me die. This was my chance to be done, to be out of pain,'" Collingwood recalls.

Given what had happened, doctors said Girton could never do ECT again.

And that's when the darkness really took over, according to Collingwood.

So every Sunday night, the couple had a ritual. Collingwood would ask his husband three questions that are recommended as part of suicide prevention and intervention.

"'Do you have suicidal thoughts?' And his answer was always, 'Yes.' He was very honest about that. 'Do you have the means, and do you have a plan?' And the answer to those two were always, 'No.' But it always was a kind of a ritual for us that we asked those questions."

They went through that ritual, and Girton gave those answers, on Sunday, May 4, of last year.

But Collingwood now suspects Girton's unusually upbeat demeanor that night came from feeling at peace about his decision. He did have means and a plan, and he carried it out the next day.

'You're Not A Burden'

While Girton was taking his own life at home, Collingwood was on the phone at work, trying to enroll his spouse in a study of a new treatment showing incredible promise for major depression that's resisted other therapies.

Collingwood says his husband just missed out on that opportunity for hope. And that's what drives this message that's become his life's mission.

"Stick around for one more day and then one more and then one more, because this doesn't tend to be permanent. There tends to be things that do work. You are a not a burden. You are not making anyone's life easier by dying. And if you're hearing these words, this is your sign. Don't take your own life today. Don't do it."

After his husband's suicide, Collingwood left a public relations career and became executive director of the Waltham-based national Families for Depression Awareness organization. He teaches people how to be vocal, supportive caregivers for their depressed loved ones and how to talk openly about suicide — a lasting tribute to the man he calls the "great love" of his life.

Resources: You can reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) and the Samaritans Statewide Hotline at 1-877-870-HOPE (4673)