Advertisement

Ozawa, Who Broke The Mold And Led The BSO For 29 Years, Gets Kennedy Center Honor

Resume

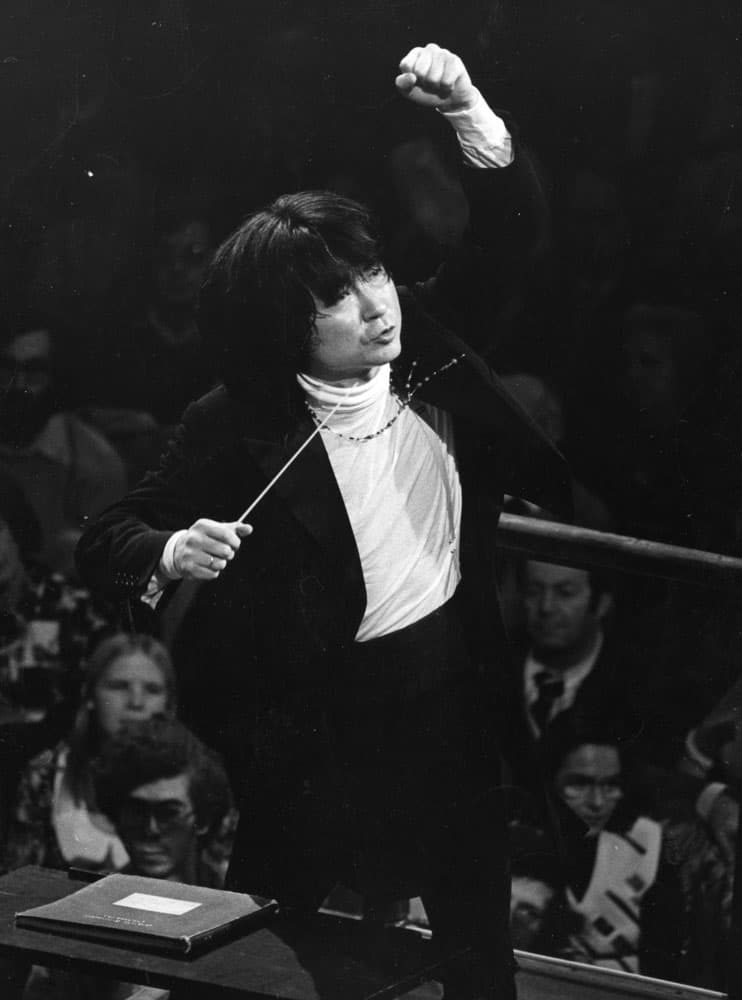

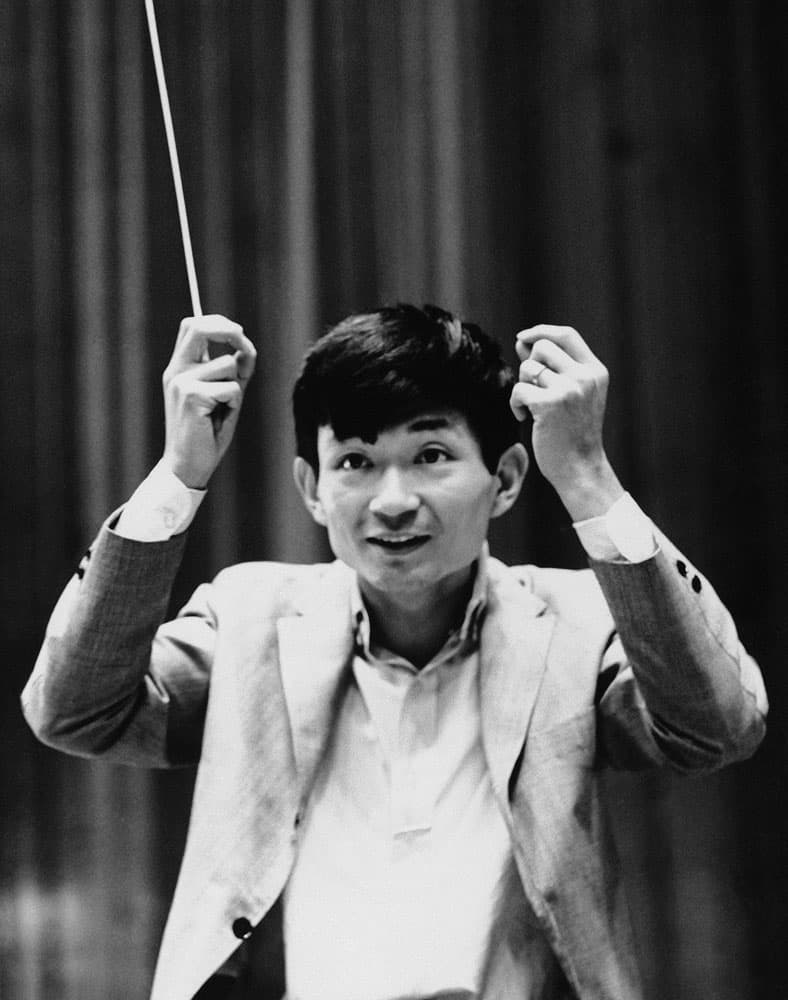

Seiji Ozawa helped change the image of classical music in the 1970s. His untraditional look and conducting style attracted new audiences — much like one of his mentors, Leonard Bernstein.

Ozawa led the Boston Symphony Orchestra for 29 years, making him the longest-serving music director in BSO history. His contribution to American culture is being recognized this weekend with a Kennedy Center honor. He'll be in Washington, D.C., for the star-studded gala, where he'll sit with President Obama and fellow celebrated artists Carole King, George Lucas, Rita Moreno and Cicely Tyson.

Ozawa stopped in Boston on his way from his home in Japan to D.C., where he caught up with old friends and colleagues at Symphony Hall.

A New Type Of Conductor

Ozawa made a huge splash when he joined the BSO in 1973. Classical music critic Lloyd Schwartz says the appointment was exciting and daring.

"He had long hair, and wore beads and turtle necks, and just didn’t look like any other Boston Symphony Orchestra conductor that anyone had ever seen," Schwartz remembered.

His BSO predecessors were more buttoned up. And they were European, with names like Leinsdorf, Steinberg, Munch and Koussevitsky. Ozawa was forging new cultural ground.

His lifelong fascination with Western classical music started early, when he was a kid in a ravaged World War II Japan. There wasn't much money or food, Ozawa recalled in an interview at Symphony Hall.

He said even with the hard times he wasn't unhappy. His parents managed to get him a piano, which he studied and played passionately — until a rugby accident altered his musical destiny.

"Two fingers were completely broken," Ozawa -- who was wearing a baseball cap and running shoes at Symphony Hall -- explained, laughing, "so I had to stop piano seriously."

Then Ozawa’s teacher Noboru Toyomasu made a suggestion. He asked his student to consider another path: conducting.

"And I never heard orchestra before, I never saw conductor," Ozawa remembered. "There was no television yet. And it’s funny — I went to a concert for [the] first time in my life. A Japanese orchestra played Beethoven No. 5 Piano Concerto."

The soloist on stage played piano and conducted, Ozawa said. For him that was a delightfully mind-blowing surprise.

When the BBC's Symphony of the Air performed in Japan, Ozawa said it opened his eyes even more.

"It was a completely different sound," Ozawa mused. "So I told myself I must go out of this country Japan to be with this kind of sound."

With his teachers’ help, Ozawa traveled to France. He went on to win an international conducting competition and was invited to study at the Tanglewood Music Center in Lenox (then called the Berkshire Music Center). Ozawa honed his chops with some of the greatest conductors of the day — Charles Munch, Herbert von Karajan in West Berlin and the dynamic Leonard Bernstein.

That was remarkable, said current BSO managing director Mark Volpe.

"This little, scrawny Japanese kid has access to Leonard Bernstein," Volpe said. "I mean this was after 'West Side Story' and 'On the Town' and 'Candide' — this is a guy who was the toast of New York. And there’s Seiji, you know, as his assistant."

That opportunity led Ozawa to lead orchestras in Toronto and San Francisco. Then the BSO, one of the "Big Five" symphony orchestras, offered him a job.

"It's amazing," Ozawa recalled. "I was very lucky," he added, smiling.

Transforming Music, Breaking Barriers

In 1974 Ozawa hosted “Evening at Symphony,” a national PBS classical music program much like the ones Bernstein spearheaded. The maestro became a celebrity, and even led an animal orchestra in an amusing skit on "The Muppet Show."

Current BSO double bass player Todd Seeber remembers watching Ozawa on TV when he was a teen in Oregon.

"He was sort of the hot ticket in the '70s," Seeber said. "He was this amazing, young, vibrant, physical conductor that was awesome with TV audiences."

Seeber got to see the maestro in action on stage at Tanglewood when he was a high school summer fellow. Ultimately, Ozawa hired the bass player to join the acclaimed orchestra.

"He becomes the music," Seeber said of Ozawa. "He always did — whether it was Beethoven or Berlioz or Stravinsky. He was incredible at bringing out sort of the primal basics of a piece."

BSO cellist Owen Young agreed, and called Ozawa's lithe movements mesmerizing.

"Anybody who has come to see Seiji conduct will notice his very fluid, ballet style of conducting," Young said. "It was very individual, very new. And that’s what stood out."

That’s not the only thing that struck the cellist about Ozawa. As a young, aspiring African-American musician, Young said seeing someone like Ozawa lead a major orchestra was inspiring.

"It told me that this career — being a musician, being a cellist — is not just for a chosen group of people," he said. "I don't know how else to say it. But it’s really, still, that if I work hard that I would also be included."

For Young, and a lot of other people, Ozawa broke the mold. He crossed cultural barriers and upended stereotypes.

Hollywood film composer John Williams agrees. "We have a lot of younger virtuosi coming now, especially from China," Williams said on the phone from LA, "but in Seiji’s generation he was alone in that, so he was certainly a pioneer." The he added: "Seiji is a beacon."

Ozawa appointed Williams to direct the Boston Pops in 1980. Williams stayed on through '93, the same year Ozawa conducted Williams’ theme for the movie "E.T." on stage. It was for the composer's birthday.

Williams explained that while he himself conducted that iconic work hundreds of times, Ozawa's touch was a revelation.

"He brought some kind of depth and line to it that -- as someone who’d recorded it, and wrote it, and played it repeatedly — had really never seen," Williams said. "It was just a perfect illustration of what a great artist can do to enliven and animate music — which is the conductor’s role, obviously."

Over the years Ozawa had his critics and controversies. In the '90s there was strife at the BSO over personnel decisions that led to resignations, bad feelings and bad press. In 2002 Ozawa left Boston to lead the Vienna State Opera.

A few years ago he was forced to stop conducting after being diagnosed with esophageal cancer. But Ozawa beat it, and the 80-year-old looks sprightly, bright-eyed and energetic with his full head of long, gray hair. He's also an extremely proud, first-time grandparent.

An Honor To His Colleagues

These days Ozawa is focusing on educating the next generation of classical musicians at academies he’s created in Japan and Switzerland.

"For me it’s wonderful to face young people — they grow up so fast — and some of them are so great," Ozawa said. "And to see or hear this is amazing. I’d like to keep that my work."

Ozawa also has his own classical festival in Matsumoto, Japan. He's continuing his mission to bring more Western music to the East.

Sitting in Symphony Hall, a place where he spent countless hours, he reflected on what it means to lead a group of passionate musicians. That, Ozawa says, is what the Kennedy Center honor is all about.

"Conductor only exists because of orchestra or chorus. Conductor doesn’t make any sound. So when I receive this, it’s with the Boston Symphony — my colleagues — together," he said. "That's how I feel."

And, who knows? Maybe the famously avid Boston sports fan will wear his Red Sox cap to the ceremony.