Advertisement

New Harvard Art Museums Show Gives Voice To Indigenous Australian Artists

Indigenous (or native) art forms are often seen as relics from the past. But a new exhibition at the Harvard Art Museums is giving voice to a vibrant population of contemporary Aboriginal artists.

Their work has rarely been seen in such a comprehensive way in the U.S. and the show's curator hopes it will help change perceptions of the art they make and their lives in Australia.

Aboriginal people have lived in Australia for 40,000 years. But much like the Native Americans in the U.S., guest curator Stephen Gilchrist says his country's indigenous populations struggle in the wake of decades of oppression, violence and dehumanization.

Standing in a gallery at the Harvard Art Museums, he shares a sympathetic kinship with local tribes in Massachusetts.

"The Mashpee Wampanoag tribe, and the Wampanoag tribe of Gay Head Aquinnah, along with the Nipmuc Nation Massachusetts people on the land of Greater Boston," the curator names.

Gilchrist is of the Yamatji people of the Inggarda language group of western Australia. He says the government there has made some amends for the historical mistreatment of indigenous people — including land repatriation. But Aborigines still fight for equal constitutional rights, housing, health care and employment.

"Australia has one of the highest standards of living in the world, but if you’re an Aboriginal person the standard of living goes down to something like 83 or something like that in terms of the rankings of the world," Gilchrist said, "so we have to ask ourselves why."

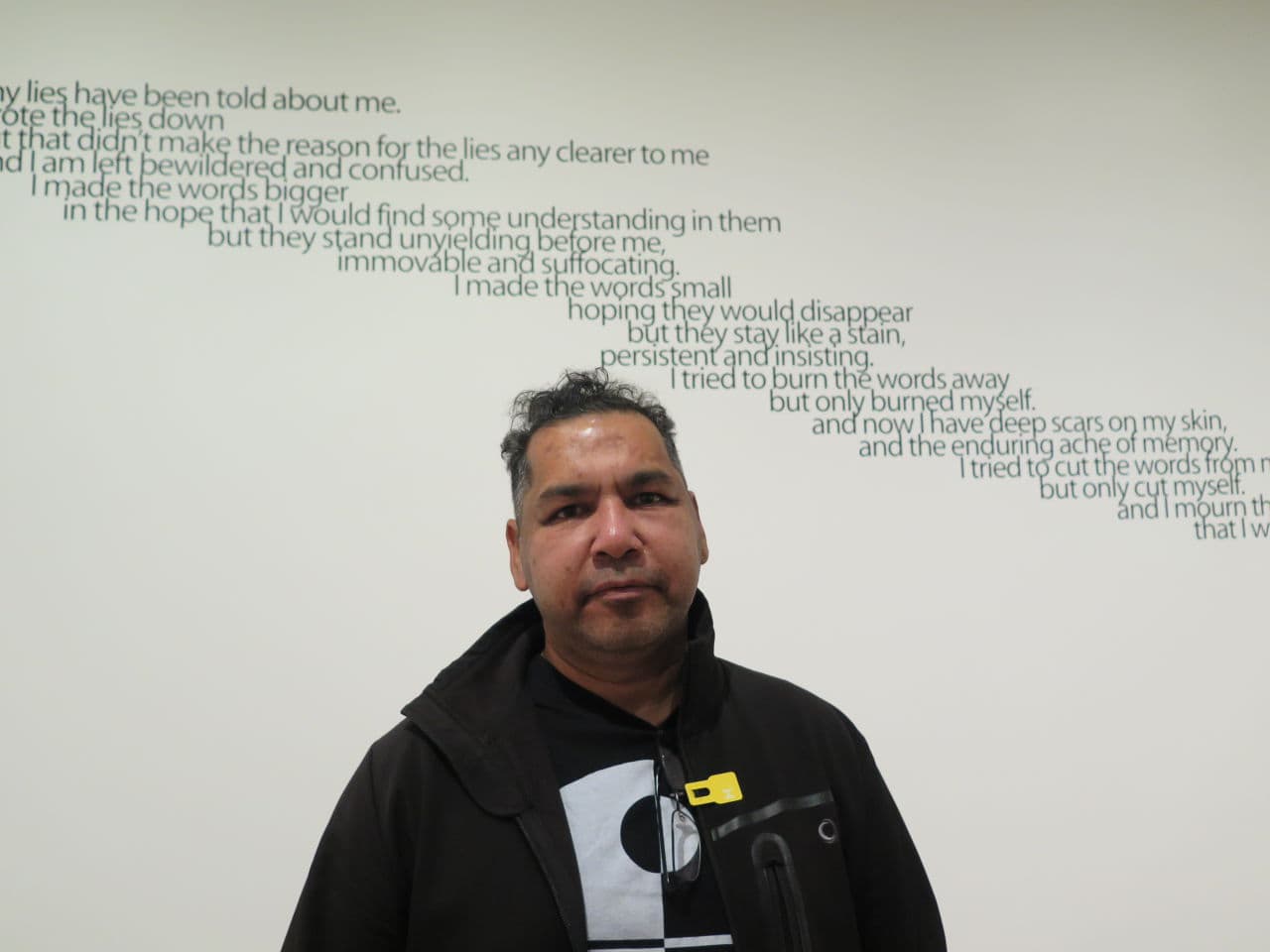

The contemporary Aboriginal artists in a new show at Harvard also have questions about their place in Australian society. The curator says half of all artists in his country self-identify as indigenous. They have their own art and cultural centers throughout the continent. But they feel their work is marginalized. Vernon Ah Kee is one of them.

"Australia espouses the existence of native people through its romanticism of Aboriginal art — and the idealism of Aboriginal art — and projects that into the world. But it’s just the art, it’s not the people," he said. "It’s worth a lot of money, but the money doesn’t go back to the people who actually make it."

And Ah Kee resents the dominant stereotype that indigenous Australian art is primitive.

"It’s a representation of Aborigines locked in the Stone Age," he said. "It never touches on the contemporary life of Aborigines. The dire poverty. You know, it never touches on the fact that we exist in Australia as a kind of non-people."

Advertisement

The museums and Harvard's Australian Studies Committee invited Gilchrist to create an exhibition that would challenge and change those perceptions. It's titled, "Everywhen: The Eternal Present of Indigenous Art from Australia."

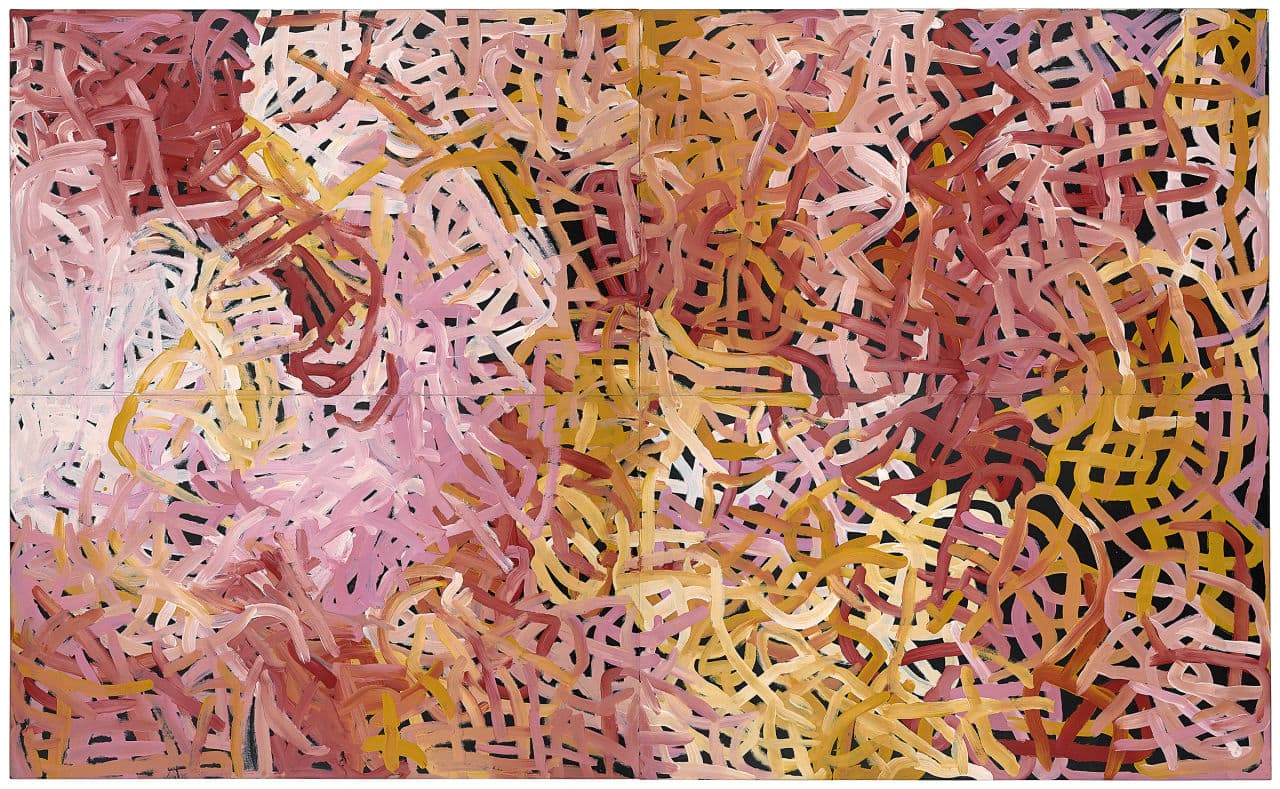

"I think people don't have a relationship with Aboriginal art," Gilchrist explained. "I really wanted to use this show as a kind of corrective and say that this is the art of now — this is contemporary art — and it’s engaged in some of the most important issues of our time."

The concept of time is the show's driving theme. The 70 works on display explore indigenous Australian culture's place in the past, present and future. Ancient narratives expressed in bark paintings made with earthy, Australian ochre pigments hang steps away from more modern-looking, glass-blown sculptures in artist Yhonnie Scarce's piece called, "The Silence of Others."

A series of black-and-white photographs titled, "We Bury Our Own," features a self-portrait of photographer Christian Thompson holding a hobby shop-type model of a colonial ship in front of his face.

Gilchrist walks over to a painting by Rover Thomas, one of the first contemporary Aboriginal artists to be recognized by the international marketplace. Before Thomas died in 1998, he expressed frustration when he encountered a work by a very famous American abstract expressionist in an Australian art museum.

"He came across a painting by Mark Rothko," Gilchrist told me, "and he immediately said, ‘That bugger paints like me.' "

Ah Kee's installation, “Many Lies,” evokes falsehoods he sees in Australian memory and history, and how indigenous people feel removed and forgotten. A cascade of words cuts diagonally across the gallery wall.

This is the full text of "Many Lies":

many lies have been told about me.

I wrote the lies down

but that didn’t make the reason for the lies any clearer to me

and I am left bewildered and confused.

I made the words bigger

in the hope that I would find some understanding in them

but they stand unyielding before me,

immovable and suffocating.

I made the words small

hoping they would disappear

but they stay like a stain,

persistent and insisting.

I tried to burn the words away

but only burned myself.

and now I have deep scars on my skin,

and the enduring ache of memory.

I tried to cut the words from my page

but only cut myself.

and I mourn the blood loss

that I will never get back.

I try to remember my life

and words that make me strong

but the lies rake and tear at my roots,

cutting me from the earth.

I live,

and all I have are pieces of truth.

but with my little pieces

I am unflinching and unforgiving.

Ah Kee hopes his work resonates with other native communities around the world, but also says he strives to be universal.

While sitting on a bench in front of "Many Lies," visitor Michael Hoffman, of Cambridge, said he connects with the artist's words.

"First the words appear and they become like a stain, and then they become like a scar, and they get deeper and deeper -- I have felt like that before — when people say things that aren’t accurate, and there’s a tendency to personalize them and take them with you," Hoffman said.

Hoffman said he's been to Australia before, but for him walking through this display of contemporary art has been a revelation.

"I wasn’t aware that the depth of the indigenous art was so great. I thought it was very backwards and simplistic," he said.

Curator Gilchrist hopes the "Everywhen" exhibition opens many other visitors' eyes. In the show's catalog he writes, “This exhibition is an invitation for us all to become synchronous with 'Everywhen' — if only momentarily.”

"Everywhen: The Eternal Present of Indigenous Art from Australia" is open at the Harvard Art Museums through Sept. 18.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly described the pigments used in some of the bark paintings. They are ochre pigments. We regret the error.

This article was originally published on February 16, 2016.