Advertisement

Even Before Pregnancy, Your Health Matters: Mom's Obesity Linked To Higher Risk Of Baby's Death

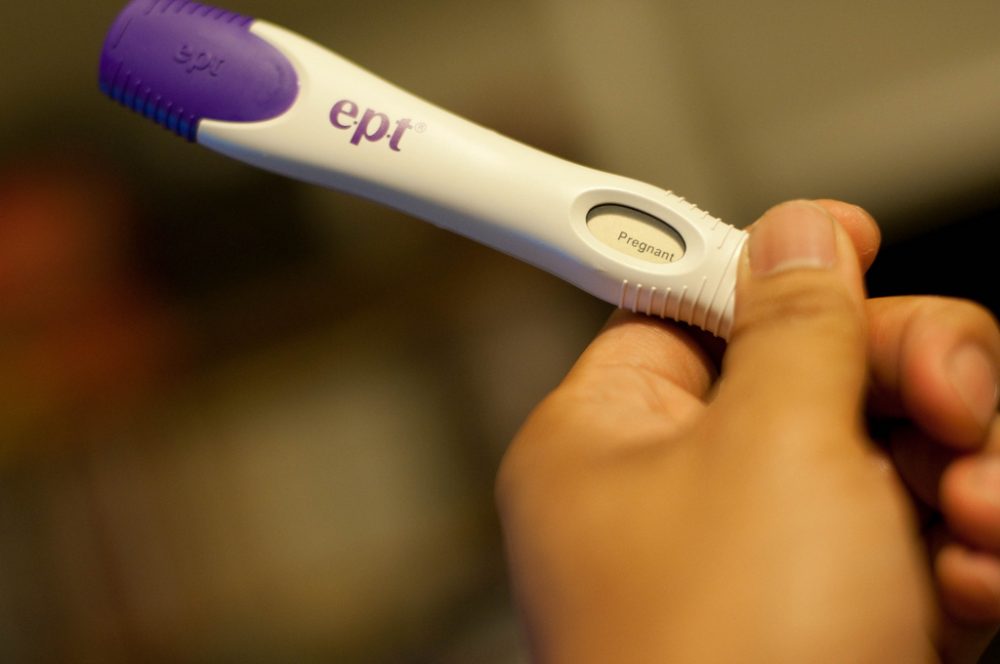

You know how it goes: The moment the pregnancy test is positive, you give up alcohol, you cut out coffee, you try to make every bite count and limit your weight gain to healthy norms. You're suddenly responsible for two.

That's the usual strategy. But new data suggest that perhaps it’s time to rethink that logic — it could be, by the time you get that pregnancy test result, you're already late for the train.

Why? According to a recent study based on a sweeping analysis of more than 6 million births, there appears to be a robust link between a woman's weight even before she gets pregnant and her baby's risk of dying in her first year.

The numbers are small, but the researchers say they are significant:

Among normal-weight moms, about four in 1,000 babies die after birth; among moderately obese moms, that rises to nearly six babies per 1,000 and among morbidly obese moms, it's more than eight babies per 1,000 live births.

(To be precise, "normal weight" for a 5-foot-4 tall woman before she's pregnant is defined from 110-144 pounds; moderately obese is considered 175-204 pounds, and morbidly obese is 235 pounds or more.)

Obesity And Infant Deaths

Eugene Declercq, the study's lead author and a professor at the Boston University School of Public Health, puts it this way: If you are truly obese, with a Body Mass Index of 40 or above before pregnancy, your baby has a 70 percent higher mortality risk compared with a normal weight woman. (This holds true even after controlling for a wide array of risk factors in the study, including race, ethnicity, education, insurance coverage, diabetes and hypertension, he said.)

“Since this involves pre-pregnancy obesity it emphasizes the importance of thinking of women’s health in general and not just when they’re pregnant, which has too often been the case.”

Eugene Declercq

It's the persistent association between BMI and infant mortality that makes the research compelling, Declercq said: As BMI increases above normal, the infant death rate increases consistently too.

"This links up women's health and kids' health in a really important way," Declercq said in an interview. What it suggests, he adds, is that pre-pregnancy BMI still had a pretty strong relationship to both neonatal mortality (death in the first 28 days) and post-neonatal mortality (death in the first 28-365 days). "No matter how you cut it, that relationship is robust."

The researchers also wondered whether pre-pregnancy obesity was related to a specific cause of death: notably, prematurity, congenital abnormalities or SIDS. As it turned out, obesity was a problem in all of those categories.

"The really powerful finding would have been if all of the higher rates of infant mortality were explained by a single cause of death, but that wasn't the case here," Declercq said. "The implication, essentially, is it's not one thing we have to worry about — obesity is a multifaceted problem in terms of outcomes."

Advertisement

An 'Alarming' Rise In Obese Women

And clearly, the implications are broad. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recently reported an "alarming" increase in the number of obese women of reproductive age in the U.S.: More than half are overweight or obese.

"A major hope in initiating this project was to get the focus on women's health throughout her life course and not just when she's pregnant," Declercq said.

Lizzie, a 32-year-old chiropractor in Medford, Massachusetts, who asked that her last name not be used, says although she's not obese, she's definitely above her ideal weight.

Recently, Lizzie's ob-gyn told her that if she wants to get pregnant (which she does), losing 10 to 20 pounds would be a good idea. "Even though I knew it intellectually, it was very hard to hear," Lizzie said in an interview. "What bothered me the most was she said it but didn't give me anything else, she didn't talk about what I should do, no specifics about exercise or nutrition."

With a family history of diabetes and a sister who had gestational diabetes during pregnancy, Lizzie says she's trying to lose weight before conceiving, but it's not easy.

"I desperately don't want to repeat what my sister went through," she said. "But it's been a challenge ... I'm a big sugar person — that's my downfall, and a daily struggle."

A Fraught Discussion

Actually getting women to lose weight before they're pregnant is far easier said than done, says Dr. Naomi Stotland, a co-author of the recent Declercq study, and an ob-gyn at University of California San Francisco.

About half of pregnancies are unplanned, she says, which makes it hard to get the message across at the right time.

In addition, says Stotland, also on the faculty at San Francisco General Hospital, pressuring women to lose weight can be tricky for both doctors and patients. "Even if a physician is motivated to talk about it, the woman might not be in the right place to hear it." she said.

For example: If a patient has an appointment to get birth control, it may not feel appropriate for the gynecologist to say, 'Hey, maybe think about losing weight for that future, theoretical birth you're not planning to have any time soon,' she said. Also, doctors' own issues about weight complicate the matter: Thin doctors often feel awkward and non-compassionate urging patients to slim down, and overweight doctors feel they have little credibility, Stotland said.

A small 2010 study of pregnant overweight and obese women, called "What My Doctor Didn't Tell Me," concluded that women often don't feel their doctors are providing appropriate or helpful (or any) information on weight.

A Too-Accessible McDonald's

And the complications only increase when poverty is also in the mix, says Dr. Nidhi Lal, a primary care doctor at Boston Medical Center. She says in her practice, which includes hundreds of reproductive age women, with about 30 to 40 percent who are overweight or obese, access to healthy food is a major obstacle because many live in so-called "food deserts" where nutritious food is scarce and fast food and convenience stores proliferate.

"McDonald's and Dunkin' Donuts and 7-11's are more accessible and affordable than shopping at Stop and Shop or Market Basket," Lal said.

She said there are often deep misconceptions about food and pregnancy. For instance, some women assume that they need to start eating for two as soon as they start planning a pregnancy. "And these are women who are already overweight to begin with," she said.

And there are cultural issues too.

"Women who are raised in the U.S. want to be thin, but they don't always have the resources to get there and so they're reluctant to talk about body weight," Lal said. "They think I'm judging them or not being empathetic." Women from certain other cultures, she says, prefer being heavy: "It's a sign of attractiveness and prosperity."

For doctors, then, it's a tough path to navigate.

"It really requires a relationship of trust, a very non-judgmental kind of communication," Lal said. "I try to make my patients well informed, tell them as many facts as I can: 'This is why I want them to do this and how it can effect their pregnancy outcomes' — a mother will do anything for the her baby. I try not to be negative, and say, 'Oh no, you gained weight.' It takes a lot pre-visit planning."

Lal also tries to get her whole medical team involved, including consults with a nutritionist and prenatal nurse. Still, she adds: "It is hard to do everything in an empathetic manner in 15 to 20 minutes because despite what you say, they have their own sense of success and failure. Some are very discouraged because they are doing what they can but some things they can't control."

But the problem isn't going away. A slew of recent studies suggest that obesity before and during pregnancy can cause enduring health woes.

A study published in January found that children born to mothers with a combination of obesity and diabetes before and during pregnancy may have up to four times the risk of developing autism spectrum disorder compared to children of women without the two conditions.

And late last year, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, calling obesity the “the most common health care problem in women of reproductive age,” issued new recommendations on obesity and exercise during pregnancy. It cited a list of problems associated with obesity mainly during pregnancy, including a higher risk of miscarriage, premature birth, stillbirth, birth defects, cardiac problems, sleep apnea, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia and venous thromboembolism, or blood clotting in the veins.

'I'm Just A Fried Clams Girl'

But telling women to change their personal behavior in an across-the-board manner sometimes gets public health officials in trouble.

For example, there was a massive backlash against the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention when, earlier this year, it issued a blanket warning that sexually active woman of childbearing age and not using birth control should stop drinking alcohol — completely.

So, hitting the right tone when it comes to talking to women about their weight is key.

"Conveying the message is tricky since I wouldn’t want it to be another case of blaming mothers," Declercq, the researcher, said. "Since this involves pre-pregnancy obesity it emphasizes the importance of thinking of women’s health in general and not just when they’re pregnant, which has too often been the case."

Interestingly, his study, published online last month in the journal Obstetrics and Gynecology, also found that established recommendations from the Institute of Medicine on weight gain during pregnancy were largely not being followed. Those recommendations suggest that obese women limit weight gain to between 11 and 20 pounds during pregnancy, regardless of the severity of the obesity. However, there was essentially the same infant mortality risk among obese women who followed those guidelines compared to those who didn’t, the study found.

That finding raises several questions: Do the guidelines need rethinking? Or is there something about the genetics of obese women that persists through pregnancy even if some amount of weight is lost?

This study didn't address those issues, but one thing is clear for any future public health efforts: Women remain far more motivated if they think they're doing something for their babies, Declercq said. The trick is to get them to think about their own health as deeply as their kids' — and well in advance.

Take Amy, a mom from Arlington, Massachusetts, who gave birth to three children through IVF (and also asked for confidentiality). Between pregnancies, she says, it got harder to lose the weight. Now, while considering a fourth child, she says she should lose about 22 pounds.

Like many moms, Amy is vigilant about feeding her children healthy meals, but when it comes to her own diet: "I can't overcome my cravings for meatball subs...I don't really enjoy eating a salad." She said that while some people find pleasure in "racing cars or smoking" her downfall is high calorie foods. "You know what you're supposed to do, but actually doing it is the hardest part," she said. "If I have the choice between romaine lettuce and fried clams? I'm just a fried clams girl."