Advertisement

How 'New Blood' Brought Beverly's Historic Movie Palace Back To Life

Once there were more than 20,000 grand movie palaces in the United States. Think the Coolidge Corner Theatre in Brookline, the Somerville Theatre, the Strand Theatre in Dorchester.

Today, though, the National Trust for Historic Preservation estimates only about 250 survive. The Cabot Theatre in Beverly is one of them.

Not too long ago it seemed to be on the verge of joining the list of lost classic movie houses. But the community here banded together to save the Cabot for 21st century audiences.

When The Cabot Was The Ware

In its heyday, Kevin O'Connor says the Ware Theater — as the Cabot was then called — brought vaudeville acts and silent movies to Beverly.

He takes me up to the balcony for a fuller view and demonstrates some quirky ways the sound moves around inside the historic structure.

O’Connor claps his hands a few times. “Hello. Hello," he says. "Great acoustics in an old theater. They don’t build them like this anymore."

Two brothers with the last name Ware built the Cabot in 1920 using the same architects who designed the Strand in Boston's Dorchester.

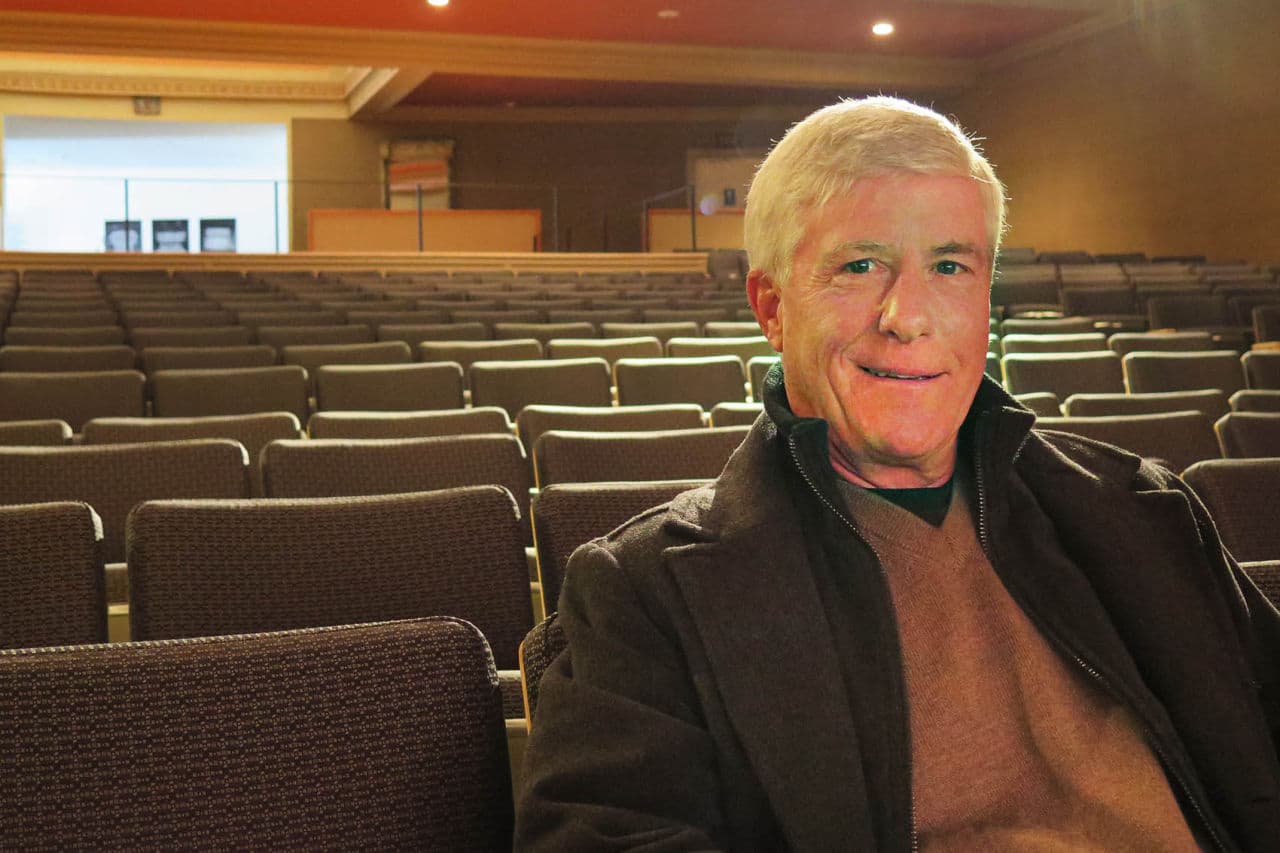

“We are looking down on what I would consider to be a majestic stage,” says O'Connor, who hosts the PBS renovation show "This Old House."

O’Connor calls the Cabot a 20th century gem.

But the movie-going experience at the Cabot in this century hasn’t been quite as glamorous. For 10 years O’Connor lived two blocks away with his wife and remembers how they'd walk here to catch a film.

“And the seats were terrible,” he says, laughing. "You were always kind of alone in the movies. But it was just a fantastic building. And I loved the fact that it was still there, that I could walk to it, that a guy in a tuxedo ripped my ticket at the front door and everything. It was just awesome, it was a throwback.”

Three years ago the theater’s owners shut its doors and put the building up for sale. It had been struggling to stay afloat as entertainment habits changed. And the building needed a lot of updating and repairs. Turns out the loss of the theater turned into a loss for the community.

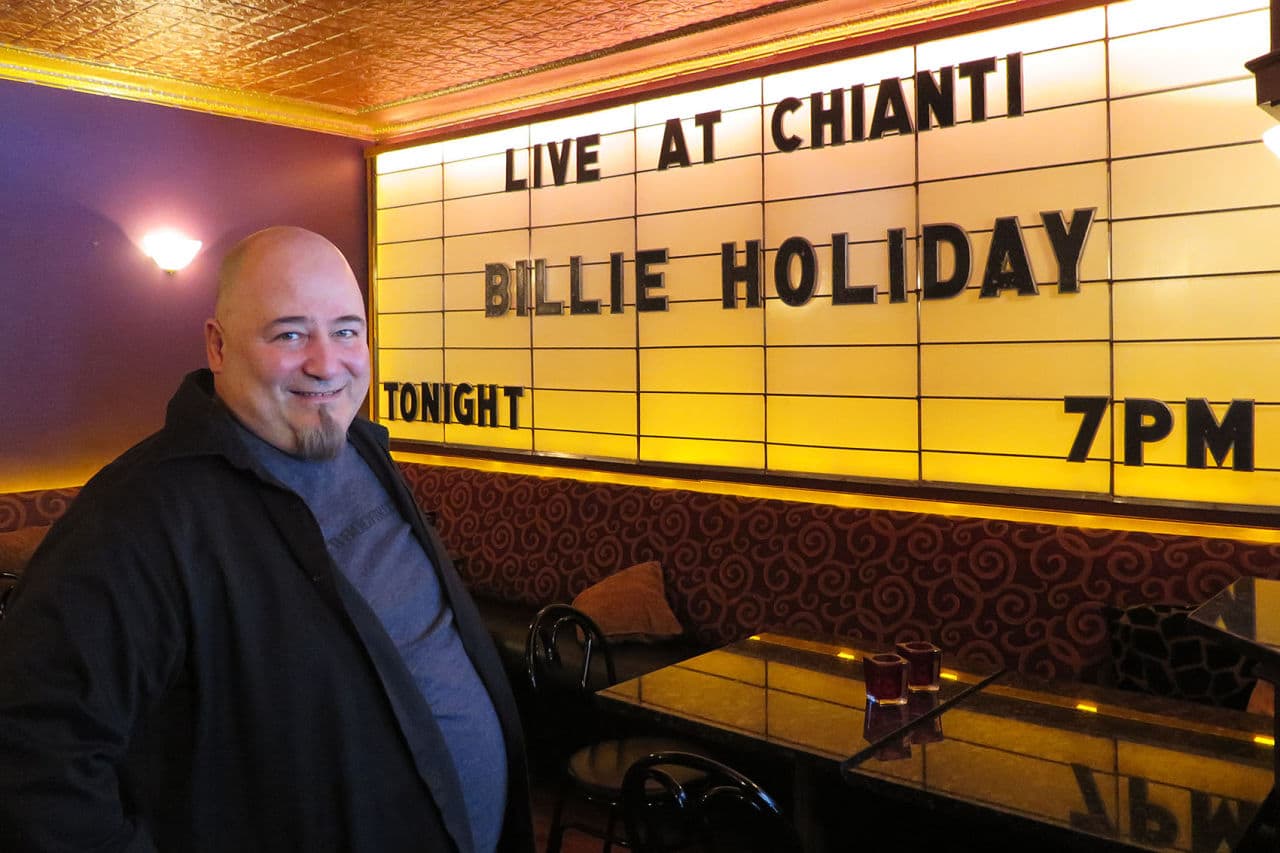

Rich Marino has owned the Chianti Jazz Club across the street from the Cabot for more than two decades and lamented the closing.

Advertisement

“There was always this great energy downtown with movies and magic and the restaurant scene,” Marino says. "So when they closed there was a vacancy in our culture, and it was very obvious.”

That’s because the person who kept the Cabot going for 37 years was gone.

Cesareo Pelaez, a charismatic Cuban-born magician, died in 2012. He bought the theater in 1976 and enchanted audiences with his high-speed/low-tech shows for decades. The Guinness Book of World Records listed “Le Grand David,” as Pelaez called his company, as the longest-running magic show in the world.

John LaPorta stared working for Pelaez fresh out of college in 1979. We talk backstage at the Cabot and he says he did whatever was necessary to support the magic show and film programming -- on and behind stage, in the projection booth, at the concession stand, at the door.

LaPorta remembers his determined, highly creative old boss well.

“He was brilliant, and unpredictable, and a lion to save this theater and keep it alive,” LaPorta says of Pelaez, “Although over ... the last 10 years of the company it started to run out of gas, and he fell on ill health and eventually passed away. So this new blood that you see here today is exactly what it needed.”

Using 'The Majestic' To Save The Cabot

The “new blood” LaPorta mentions is a group that formed to save the Cabot as other business owners started sniffing around the property. It includes "This Old House's" O’Connor and restaurant owner Marino.

Marino watched with binoculars from across the street as real estate agents gave tours to prospective buyers. He and many others worried the Cabot would become condos.

“The question was, ‘How could we get, you know, business people that support the arts to come up and help save this theater?' ” Marino remembers asking.

Turns out tapping into their nostalgia was a start. And Marino has plenty of that. The first date he had with his wife was actually at the Cabot’s magic show 20-something years ago.

And Marino says, “My favorite movie in the world is a movie called 'The Majestic,' which is about a town saving a theater. In fact my 7-year-old son is named after the lead character in 'The Majestic.' ”

Marino actually sent a clip of his favorite scene — with actors Jim Carrey and Martin Landau — to locals he thought might want to get involved and finance the crusade.

In the scene, Carrey says: “This place is ready to fall down. All you'd have to do is walk outside and give it a good shove.”

Landau replies: “You’re wrong. You are, you know. I know she doesn't look like much now, but once, once this place was like a palace!”

The film's community spirit spoke to entrepreneur/philanthropist Henry Bertolon, who's lived in Beverly for more than three decades.

“You think about communities, right? And you think about gathering. And you think about cocooning. But people still want to gather and they need places to gather,” he says, sitting in the Cabot’s front row.

After many discussions -- and some convincing — Bertolon bought the old theater for $1.2 million with the understanding that the nonprofit formed by the group would eventually buy it back.

“Next thing we know I own this theater,” he recalls, laughing, “and it was kind of funny because we’re talking about, 'What we do now?' ”

They decided to reopen the historic theater immediately, renamed it the Cabot Performing Arts Center, and planned to show movies and switch things up by bringing in some major musicians for live concerts.

But Bertolon says it didn’t take long for reality to set in.

“It was rough," he says. "We didn’t know what talent to really book. We had to rent the sound systems. Every time we rented something it took away from any potential profits that we had. But it was really exciting, right, ‘cause we had this place come alive, and we were having these shows and it was fun trying to figure it out, and it was a lot of hard work and we were in here, you know, painting the bathrooms and doing whatever we had to do to just keep the thing band-aided together.”

The group eventually installed new lighting, sound and digital projection systems, upgraded the stage, and raised $250,000 for new seats. And the nonprofit bought the Cabot back from Bertolon.

He remains on the board of trustees, but the biggest payoff for him is seeing Beverly revived, too.

The band Rusted Root appeared recently and Bertolon paints the scene in a restaurant he went to before the concert. “It is packed, 80 percent of the people were going to the show. The place was rockin’!”

'The Nostalgia Will Only Go So Far'

“I’ve been working in old theaters since I was 18, starting at the Orpheum Theatre in Boston doing every little job you can imagine, so it’s always been a dream of mind to be involved in saving an old theater,” says the Cabot's new executive director, Casey Soward.

Soward takes me up to the Cabot’s roof to show me the town. He said he goes up there a lot.

“This theater isn’t just for Beverly. This is a regional resource,” he says.

Soward says there are many challenges to overcome. “This old building is the best and worst about this organization,” he muses, “because it’s beautiful and you could never replicate anything like this today, but it’s extremely needy in terms of its maintenance.”

So things are surely looking up for the Cabot. But O’Connor says the team has an ongoing responsibility to make sure the Cabot remains relevant while they preserve it for the long haul.

“You know at the end of the day the nostalgia of the building will only go so far,” he explains. “People need to walk in here and they need to see great entertainment, really good acts, and have a great experience — and that requires people working at that seven days a week.”

It also requires heat. The next major project at the Cabot is a new HVAC system, because I’m told if you come to the historic theater on a really cold night, you should bring your jacket.

Correction: An earlier version of this story included a photograph that wasn't of the magician Cesareo Pelaez. We regret the error.

This article was originally published on April 01, 2016.