Advertisement

In 'Jackie Robinson,' Ken Burns Shows A Civil Rights Champion As Well As A Baseball Icon

Before Rosa Parks refused to relinquish her bus seat to a white man, before the U.S. Supreme Court struck down school segregation, before Martin Luther King shared his dream with the world, there was Jackie Robinson.

Sixty-nine years ago this week, Robinson became the first African-American to break Major League Baseball’s color line, which had kept the national pastime white for more than 50 years. All MLB teams will honor him on Friday, its annual Jackie Robinson Day, by wearing his uniform number, 42, which was universally retired in 1997.

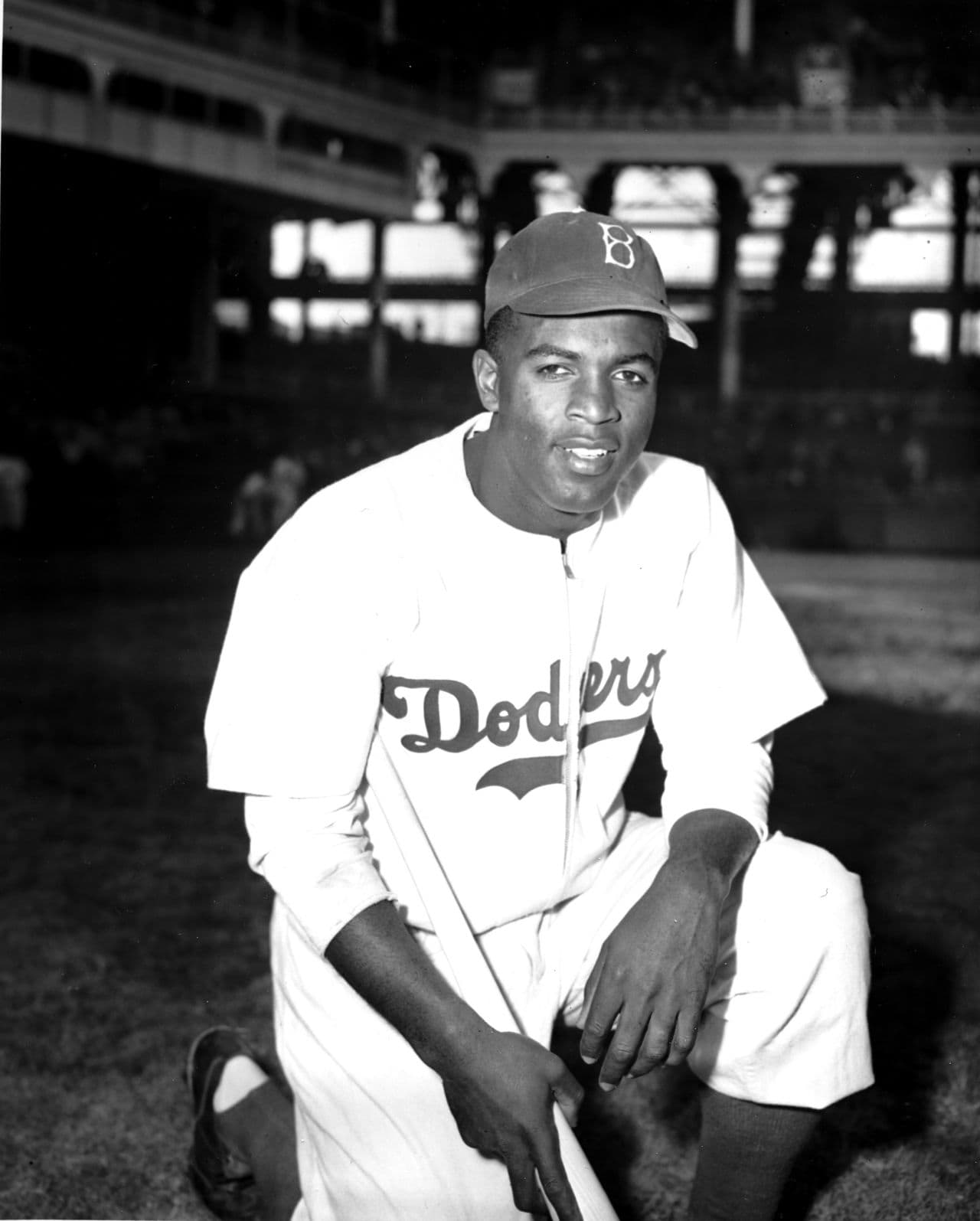

His debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947, did not just change baseball, although, with his flair and speed, Robinson certainly did that. It changed this nation, proving (again) to whites that, given an opportunity, black people can excel. Even more poignantly, it gave African-Americans an unmatched hero, and a chance to claim another piece of a dream long deferred.

From his landmark “The Civil War” to “The Central Park Five,” about a group of black and Latino teens wrongly convicted of raping a white woman, race is the tie that binds the best work of documentarian Ken Burns. With his latest film, “Jackie Robinson,” made with Sarah Burns and David McMahon, he continues to explore a subject that has scarred this country for nearly five centuries. Narrated by actor Keith David, this two-part film starting Monday night on WGBH is triumphant and heartbreaking, a superb portrait of Robinson, the outstanding player on the diamond and the determined activist who never stopped fighting for civil rights.

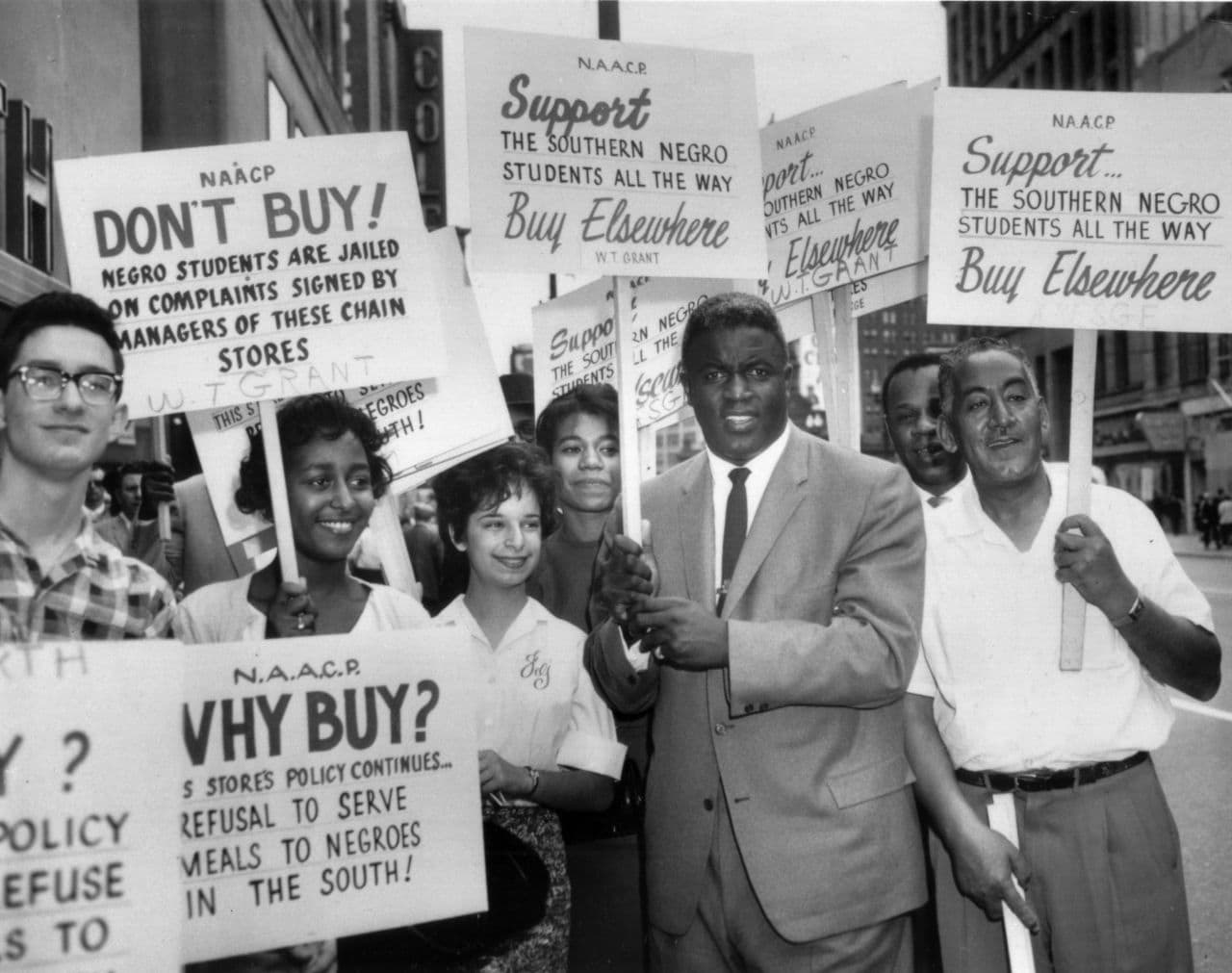

“Part of what I admire about Jackie Robinson is precisely his ability to approach baseball, and those first two years of integration, in ways that were contrary to his character, or his fundamental sense of what was right and wrong, in service of a larger cause,” says President Barack Obama, who uniquely understands the great weight and solitary path that comes with being black and a first. “But that’s not something that made sense for him to sustain. He had purchased the right to speak his mind many times over.”

When Branch Rickey, the Dodgers’ general manager, wanted to integrate the majors, he wanted a man with talent, but also the temperament to endure the inevitable racist torrent at home, and on the road. This made Robinson a curious choice. Growing up in rural Georgia, Robinson, the grandson of slaves and son of a sharecropper, felt racism’s sting early, but would not bend to bigotry. From childhood through his military years, the film cites numerous examples of the young Robinson agitating for the rights he and other African-Americans were routinely denied, shattering the stubborn image of Robinson as docile. Still, recognizing the impact he could have, Robinson agreed to be part of Rickey’s “noble experiment.”

Advertisement

That experiment was rife with tribulations. Opposing teams threatened to strike. Some of his own teammates denounced him. Black cats were tossed onto the field. Pitchers threw high and hard at his head, base runners tried to spike him with their cleats. There were death threats. The Philadelphia Phillies’ hateful manager, Ben Chapman, spewed vile comments at Robinson during games. Robinson bore each provocation in silence. (Philadelphia officials recently passed a resolution officially apologizing for Robinson’s treatment in 1947; it will be presented to Rachel Robinson, his widow, on Jackie Robinson Day.)

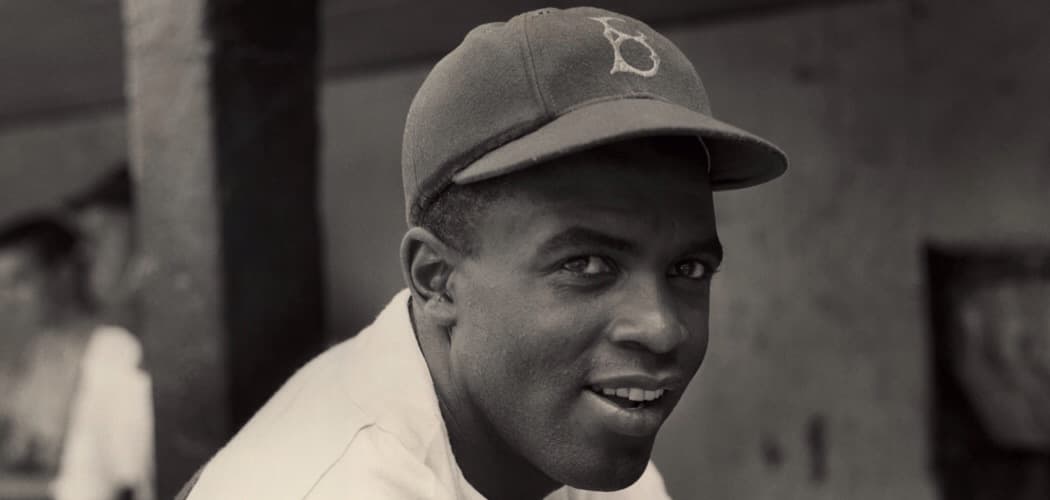

Despite that first exasperating year, Robinson helped lead his team to the World Series. His play was as dazzling as his smile, and there’s an astonishing clip here of Robinson turning a bunt into a standup triple. He would become the first player named Rookie of the Year; but he could not stay in the same hotels or eat in the same restaurants as his teammates. Robinson was, as legendary sportswriter Jimmy Cannon put it, “the loneliest man I’ve ever seen in sports.”

What sustained Robinson was his wife, Rachel, whose steadfast, abiding love is still abundant in the film’s many interview segments. She was his rock and created for her husband a sanctuary from the hate many held in ample supply. First Lady Michelle Obama acknowledges the vital role of a supportive spouse, and the character it takes to choose not just a wife, but also an equal partner. (As she speaks, her husband’s smile is humorous and touching.)

Robinson also relished being a humble icon in black communities, and inspiring future stars like Willie Mays and Don Newcombe, both interviewed here. And in cheering Robinson, many African-Americans -- including my family — became lifelong baseball fans.

Silence did not suit Robinson, and as his career progressed, he spoke more candidly. He criticized the all-white New York Yankees as prejudiced, and would later say the same of the Boston Red Sox, which, 12 years after Robinson’s MLB debut, became the last team to integrate. Whites resented Robinson’s outspokenness, while blacks fretted that his statements would undo whatever progress he’d garnered for their race.

“As long as I appeared to ignore insult and injury, I was a martyred hero,” says actor Jamie Foxx, who recites Robinson’s own words. “But the minute I began to argue, the minute I began to sound off, I became a swellhead, a wiseguy, an uppity nigger. When a white player did it, he had spirit. When a black player did it, he was ungrateful.”