Advertisement

Beyond Textbooks: Mass. Schools Find New Ways To Teach Racial History

This is the first part of a two-part report on discussing racial issues in the classroom. Click here for part 2.

Textbooks are often thought of as a critical tool for teachers in the classroom. But when it comes to teaching the history of race in the United States, WBUR has found that more and more teachers in Massachusetts are moving away from traditional textbooks.

At Lowell High School, social studies teacher Robert De Lossa opened up a 20-year-old textbook, "A History of the United States,” by Ruth Frankel Boorstin, Daniel J. Boorstin and Brooks Mather Kelley. Published by Prentice Hall, which is now owned by Pearson, the book is about 1,000 pages long.

As De Lossa flipped through the pages, he arrived at the passage he was looking for — on one of just 10 pages in this 1,000-page book that cover the contributions of minorities to U.S. history. It’s a chapter on the 1960s civil rights movement. And it's called "The Problem of Civil Rights: The Black Revolt."

“One of the things that troubles me as an educator,” said De Lossa, “is that it’s almost antagonistic in its language. So a student who would be using a textbook like this, the last images they would have on the black rights movement is that it's revolt, it's rebellion and it’s problematic.”

De Lossa now uses an updated version of a textbook by the same publisher, but he noted that the older version is still in use.

“The problem that we have, and the problem that a lot of schools have, is I’ve got over a thousand copies of this,” said De Lossa. “To adopt fully a new text that has the characteristics that we want would be over $100,000.”

De Lossa’s dilemma is one that teachers throughout Massachusetts share. Teachers we spoke with said that, while they are frustrated by the way some textbooks teach about the contributions of minorities, they can’t afford to replace the books. Many instead work around the problem by using digital and primary sources, as well as audio and visual materials.

Recently, there’s been particular interest in this topic. This month in Texas, parents and activists voiced their concerns to the Texas Board of Education over a textbook entitled “Mexican American Heritage.” Some scholars say the text is riddled with factual errors and promotes offensive stereotypes. And in 2010, Texas changed its social studies curriculum to what some have complained is the whitewashing of U.S. history.

Advertisement

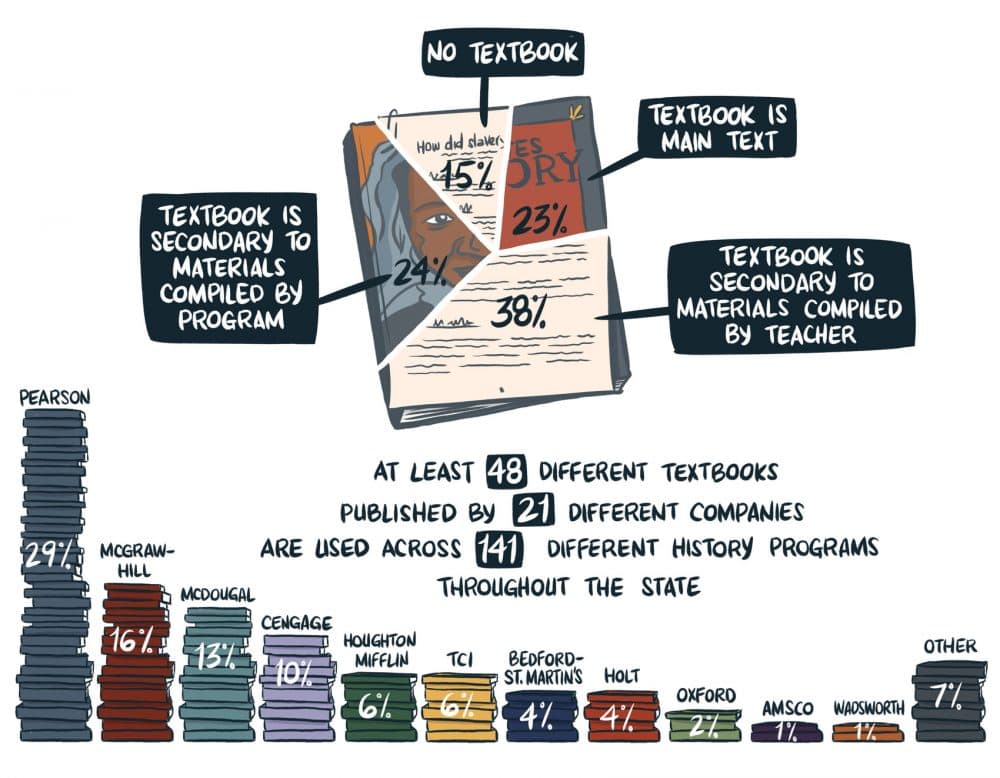

Here in Massachusetts, WBUR contacted 283 districts in Greater Boston to find out what textbooks they use to teach U.S. history in high school; 141 districts responded. We found that those 141 programs use at least 48 different textbooks, published by 21 different companies.

The history textbooks used most in these Massachusetts public high schools are published by Pearson, the parent company of Prentice Hall. Pearson is also a popular publisher in Texas. Some have argued the textbooks are often written with the conservative textbook standards of Texas in mind, because that state is the nation's second-largest textbook buyer.

In a statement, Pearson representative Scott Overland said, “Pearson curriculum is developed by expert author teams that are well regarded in their fields of study and are reviewed by independent, academic reviewers. In Massachusetts, as in other states, we regularly review and update our textbooks to ensure they are aligned to the state's curriculum frameworks.”

Massachusetts provides clear guidelines on what to teach, but districts and teachers have lots of latitude on how they teach.

Codman Academy principal Thabiti Brown said when it comes to teaching U.S. history, Codman, like other schools, does not use textbooks as its main source. Instead, it focuses on primary sources, articles and other materials. His school is in the heart of Dorchester, a racially mixed community, and he said it’s imperative for his students to see themselves in the history they are taught.

“If one of our years of study is about the birth of the nation through Reconstruction, that is really a study of white, landed, heterosexual men making all these decisions about everyone else," Brown said. "I think that’s too narrow of a viewpoint. It’s an important viewpoint to understand and have students understand that’s a part of history, but it can’t be the only story that’s told.”

In Cambridge, history and social science coordinator Adrienne Stang noticed something over the summer while looking through old history books for the district's fourth graders. It was the cover of a book about Native Americans, called "Life of the Sioux Indians," that caught her eye.

“What I see here is a girl with kind of wavy blonde hair, a white girl, on a horse next to a very light-skinned Native American boy,” said Stang. “And if you look at the book, it’s looking at the period between 1800 and 1850, and the image makes no sense in any way during that time period.”

Stang said a white girl would likely not have been riding a horse with a Native American boy. And the term "Sioux" is outdated, she said, although she noted that, to be fair, the book was published in 1973.

For decades, however, students have been reading this book. Stang said for districts that can’t afford to order new books, ones like this are actually a way for teachers to open up a dialogue about what might be right and wrong about it.

“There is not one narrative," Stang said. "History is really a debate about the past, and we want kids to engage in that debate. So textbooks are a resource, but one of many — and, from my point of view, not the important resource.”

Of the 141 districts we spoke with, we found that more than half, 64 percent, use textbooks as a secondary source, not the main one.

“The movement in pedagogy is away from textbooks and toward unit work focused on original source material and instructional activities that scaffold toward a performance-based assessment,” said De Lossa. “Textbooks are important as reference resources, and they give a good chronological sense of the flow of history. Still, I and many others feel that following the textbook slavishly day after day does not lay a foundation for the strongest history education possible.”

Updated to clarify that the "conservative standards" in Texas refer specifically to standards for textbooks.

WBUR's Edify intern Catherine Kulke contributed research to this report.

This article was originally published on September 19, 2016.

This segment aired on September 19, 2016.