Advertisement

The Detective And The Dealer: An Evening With Heroin In Framingham

One detective hides behind the house. Another is in an unmarked car out front. A third and fourth are stationed along a narrow residential street as a tall man with shoulder-length dark hair lopes toward a double-decker.

The man, baseball cap pulled low, crosses an intersection and turns into a driveway.

"You got the porch?" a commanding officer asks, his voice cracking in the static of a two-way radio. "I will in a minute," answers a detective who shifts his position so that the back porch of the house is within sight.

"It’s key for us now to keep eyes on the informant at all times," says Framingham Sergeant Sean Riley, whose narcotics unit is running what's called a controlled drug buy.

This is how local police tackle the heroin and fentanyl epidemic — one buy at a time. The buys help police collect evidence that someone is dealing drugs, seek a search warrant, arrest the alleged dealer, and choke off one pipeline in the flood of heroin onto Framingham streets.

There's an urgency in the state's largest town, as 120 men and women have overdosed so far this year -- a 50 percent increase in one year. Last year in Framingham, there were 12 deaths. The number of deceased is not confirmed so far this year, but police expect it will be higher.

Gov. Charlie Baker and others have focused a lot of attention on reducing the number of opioids prescribed for pain because that's where an addiction often starts. But if those former patients overdose and die, the killer is typically something bought on the street -- heroin or an illicit version of fentanyl. Many police and public health experts say that without more attention to the street supply of heroin and fentanyl, the opioid epidemic will rage on.

So we went to Framingham to find out how heroin and fentanyl end up in the hands of users, and how police battle the problem. On a cool fall evening, we rode along with members of the Metrowest Drug Task Force, a partnership that includes detectives from Framingham and Natick. And we drove the same Framingham streets with a former heroin dealer.

Advertisement

We'll take you into both worlds. We return to the driveway of a house where police have seen a lot of "activity" — people coming and going at all hours of the day and night.

'The Target'

The man with a baseball cap is an informant who was charged with possession of heroin a few years ago. Now, he's helping the officers who arrested him try to shut down trafficking at this house. The informant heads for a backdoor where he expects to see the dealer, the target of this buy.

"Appears the target just came out," says a detective using the secure police channel, "standing next to him on the porch."

The informant has $100 that police withdrew from a narcotics investigation account. Detectives frisked the man for weapons, drugs and other money. They ran cellphone numbers from the informant’s phone through a national police database, just to make sure that the target is not an undercover federal or state police agent. With all these steps cleared, the detective assigned to the informant, his handler, drops the man a few blocks from the house, and pulls his unmarked car with tinted windows into a parking lot.

"This is a really tough spot for us to do surveillance on because there’s a lot of counter-surveillance," Riley says.

"All right, our boy’s away," reports the detective closest to the house. "Target went back in the left side door."

In the police car, Riley leans forward, "just watch out here for a second," he says under his breath.

The informant is yelling over his shoulder to a guy about 10 steps back. Is he being followed? No, the follower turns right as the informant crosses an intersection and reaches the unmarked car.

"All right we got him, we’re good," says the informant's handler.

'Heroin Just Skyrocketed'

Two years ago, the target in this buy, that guy on the back porch, might have been the man who takes us on a tour of these same Framingham streets.

"When I first started dealing drugs it was just coke. Then two or three years ago, once the doctors stopped being able to give scripts to people, that's when the heroin just skyrocketed," says the man who appears to be in his late 20s. We've agreed not to use his name or any information that might reveal his identify.

"I would sell to people working in hospitals, working with kids, people working in institutions like jails," he says. The man tells us he was a mid-level dealer.

"I worked up to picking up 100 grams every couple of days and you'd be surprised how fast that goes," he says.

He was making a lot of money — $3,000 to $4,000 a day. In one six-month period, he says he saved $35,000, even while spending money on just about anything he wanted: diamond chains, gold watches, strip clubs every night.

'That's So Minuscule'

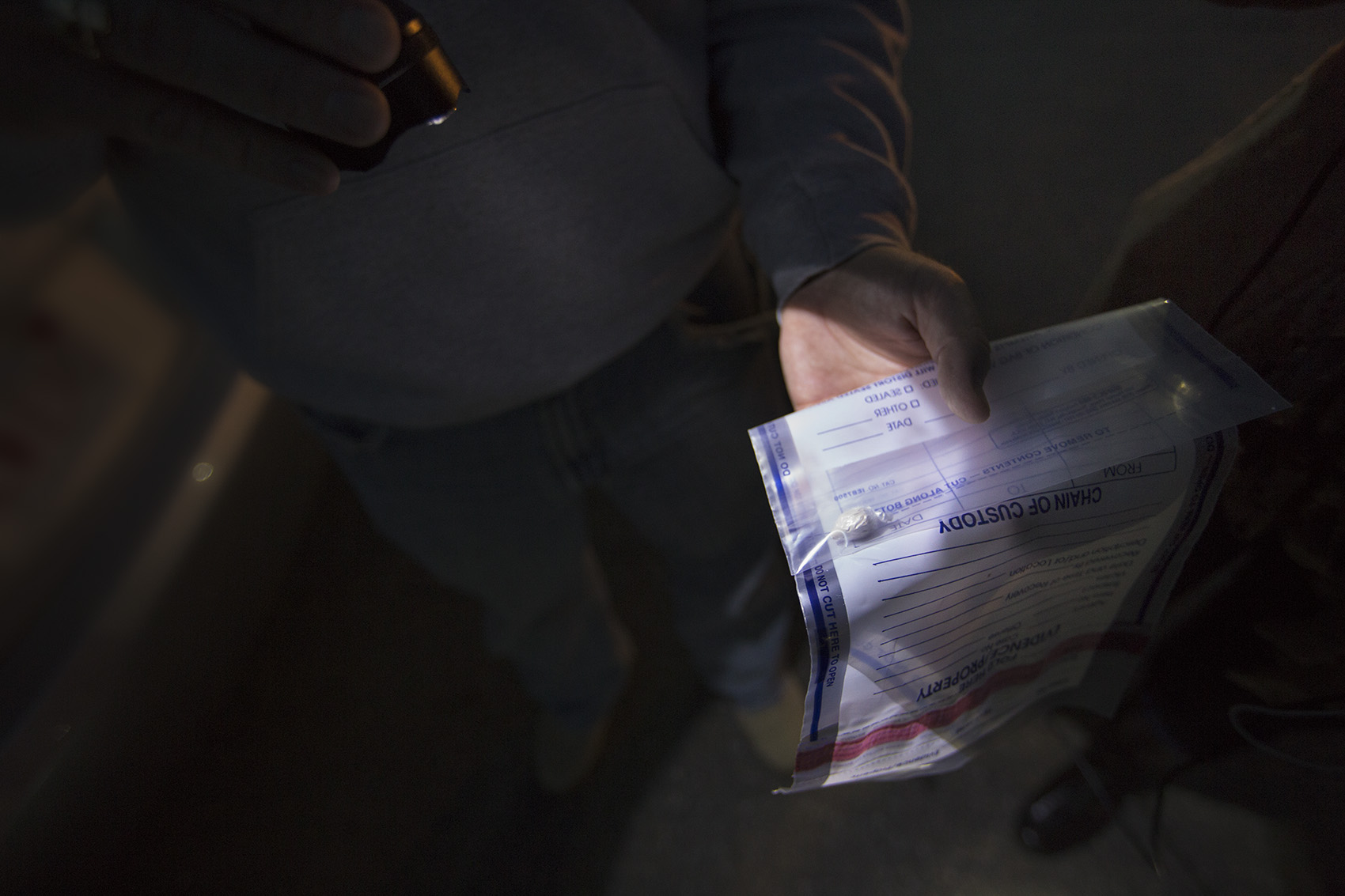

As darkness falls, detectives take the informant to a deserted parking lot across from MCI-Framingham. He hands over a plastic bag of brownish powder, about the size of a gumball.

"In the Metrowest area, that's $100 worth of heroin, about 1 gram," says Riley, rolling the bag between his fingers. The price could be half that, or less, in some bigger cities.

The informant will get $40 for his work, a tiny fraction of what he could make dealing heroin for an hour. Detectives put the informant back in the car after patting him down to make sure he didn't make any side deals or keep some of the heroin for himself.

Riley will aim for three such buys before seeking a search warrant on the target, who Riley suspects is dealing a substantial amount of heroin.

So, what percentage of heroin on the streets, at this moment, does this 1 gram represent?

"Oh man, that's so minuscule, that's nothing," Riley says. "I mean, if that one house was selling heroin, you could have 15 or 20 other people dealing heroin all at the same time."

Riley's unit searched a house across the street from this night’s target just a few months ago.

"I wish I could say that was, that we're hitting the source of the supply here in Framingham," Riley says, then pauses. "We’re really, I think, just trying to keep people on their toes and slow down the supply out there. That’s really — are we ever going to stop it? Probably not."

'A Few Free Samples'

The unending supply is feeding what seems to be a never-ending demand. The former dealer says he thinks the heroin he bought came into the country from Mexico, although he's not certain. He says he dealt with about six people who could sell large quantities of heroin wholesale.

The dealer had lots of regular buyers who'd spend as much as $250 a day on heroin. But he was always looking for new clients.

"If you know what you're doing, you would bag up little samples and hit areas like this downtown, this whole strip," he says as we drive through a congested area near the train station, past a Tedeschi's.

"I can walk by here, give people a few free samples and give them my phone number, and wait," he says. He'd look, specifically, for drug users in treatment.

"I would go to the clinic or one of the offices that prescribe Suboxone and wait outside," he says. "Or AA meetings or NA meetings. As soon as the meetings are done, you know who is active and using and who is taking their sobriety seriously. So you approach those people."

Giving free samples was key to getting customers and maintaining their loyalty. The dealer says he would often go to parks early in the morning and look for heroin users who were sick, in the throes of an opioid withdrawal.

"Once you give someone a free sample," the man explains, "to the addict it's huge, to them it's like you're taking care of me — even though you're really kind of destroying them."

'No Doubt About It, That's Heroin'

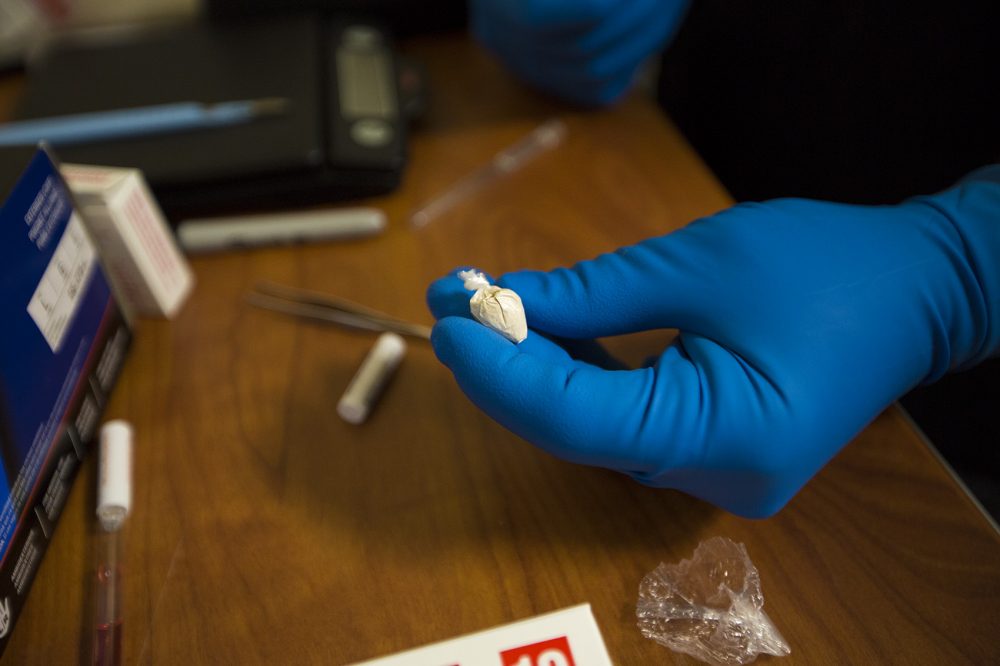

Detectives from Natick and Framingham bring the 1-gram bag of heroin back to a small office at the police department. In the narcotics unit, Detective Joe Godino snaps on blue latex gloves.

"We’ve been testing a lot of fentanyl, so we usually wear gloves," Godino says, to explain this extra precaution police take with the opioid that's up to 50 times more powerful than heroin.

Police keep naloxone, the drug that could help reverse an overdose, in the office in case detectives accidentally inhale fentanyl or get it on their skin.

Godina pulls a pair of tweezers from a drawer and picks at a minute knot atop the gumball-size plastic bag. Dealers cut the corners off sandwich bags and fill the triangle with heroin, fentanyl, powder or other additives. They spin the bag and tie it off.

When Godina opens the pouch, he discovers this gram of heroin is double-bagged.

"You’ll see this a lot with people who sell it out of their mouths," Godino says. "They want to make sure it’s not leaking in their mouths when they carry it. Or if they swallow it, they want to make sure they can go to the bathroom and have it come back out."

Godina scoops a pinch of the powder into a small test tube. He bangs the tub to activate a chemical inside. If the mixture turns yellow, the drug is fentanyl. In this case, it flashes purple.

"And that’s how you know that this is heroin," Godino says. "No doubt about it, that’s heroin."

Godino puts the heroin into a large plastic bag with the test results. It will be stored in the evidence room. A Framingham police officer is under investigation because of money missing from the room. One criminal case has been dismissed as a result.

Leaders of the Metrowest Drug Task Force say they could keep 25 detectives busy all day following up on tips like the one that led them to this heroin buy.

'The Money Controls You'

The former drug dealer says he stopped dealing after he was arrested, but managed to evade police for several years.

"I'll find an addict who has an apartment and I'll give him a couple bags a day," the man says, "so I can sell drugs out of his apartment all day. When the cops come and get a warrant for that apartment, that apartment is not under my name."

The plan worked for a while, he says, but was stressful.

"The thing is, you can't trust anyone, you're always watching your back," the former dealer says. "You have to literally watch where you're going, watch who you're talking to, have eyes behind your head."

The man says he never had any serious injuries, but there were close calls. He feels lucky to be alive.

"I've earned my respect. If I had to do something to someone because they owed me money or they shorted me, then I did it," he says. "If that's hurting someone or whatever — well I had to do what I had to do."

There was an ever-present fear that police or rival dealers might kick in his door, and very little sleep.

"It's a nightmare," he says, shaking his head. "When you're out of it you're like, 'I don't know how I did that.' But when you're in the moment, in the zone, the money controls you."

Our former dealer and the Metrowest detectives live in competing worlds, but they agree about the best way to fight opioid addiction: The focus, they say, must be on slowing the demand for drugs.

"You can get rid of the supplier all day, but if the user still needs his product or her product, they’re just going to go find the other dealer," Riley, says "and they're just going to keep on pumping it out."

Still, the task force forges ahead, while the rate of opioid overdoses and deaths continues to rise in Framingham, Natick and across Massachusetts. The latest state numbers show that five people die every day, on average, because of opioid use.

Riley says with every arrest, he hopes to make it a little harder for a few users to get heroin or fentanyl.

"Maybe it takes one or two people and it turns them around," Riley says. "I look at that as a success."

Framingham police are among the departments that have started guaranteeing treatment to users who overdose. And the department is working with local health and school leaders on substance use prevention projects, realizing there's no magic bullet that will stop the waves of opioids hitting their streets.

This segment aired on December 16, 2016.