Advertisement

The Wonderful, Woeful World Of Haruki Murakami's 'Men Without Women'

Whenever I try to explain why Percy Faith’s 1959 “Theme From ‘A Summer Place’ ” is such an integral part of my playlist, my wife looks at me like I have two heads. So I’m going to let Haruki Murakami, or at least one of his characters, have a go:

“When I listen to this music I feel like I’m in a wide-open, empty place. It’s a vast space, with nothing to close it off. No walls, no ceiling. I don’t need to think, don’t need to say anything, or do anything. Just being there is enough. I close my eyes and give myself up to the beautiful strings. There’s no headaches, no sensitivity to cold … Everything is simply beautiful, peaceful, flowing. I can just be … I’m sure in heaven Percy Faith is playing the background music.”

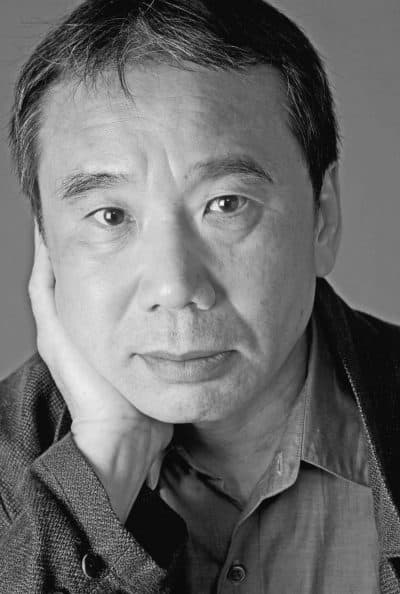

But we’re less interested in Percy Faith today than in the Japanese writer of those words. Murakami is a master of taking what seem to be everyday occurrences, and even trite sentiments, and investing them with mystery and even majesty.

His MO in doing so is not to everyone’s taste, perhaps even less so in recent years as many critics think that his turn of the millennium masterpieces like “The Wind-Up Bird Chronicles” and “Kafka on the Shore” make his later fiction look either insignificant or, in the case of "IQ84," bloated.

I’m not one of them. His new collection of short stories, “Men Without Women,” could be reduced to a cliché as one character after another learns the crucial importance of not settling for a life lived as an honorable observer, but as a full-fledged participant. But to say that Murakami’s stories here are defined by a yearning for commitment is no more telling than saying Alice Munro’s short stories are defined by ambivalence. Yes, but ...

It’s how Murakami investigates themes of loneliness and loss, creating a special world enlivened by his own unique form of magical realism, that makes “Men Without Women” a collection rich in poetry and perspective.

The typical Murakami central character here enjoys a good life — good food, good music, good sex — but there’s something missing, a hole that invites personal and even political disaster.

Kino, the title character of one of his stories, is told by a mystical soul (but one who isn’t afraid of getting his hands dirty): “You’re not the type who would willingly do something wrong. I know that very well. But there are times in this world when it’s not enough just not to do the wrong thing. Some people use that blank space as a kind of loophole.”

Kino left his wife after he discovered her in bed with another man. Off he went to a remote place in Japan where he took over his aunt’s bar, allowing him to offer a cozy atmosphere to a limited clientele, where he plays jazz all day. (Clifford Brown, The Beatles, Beethoven and, of course, Percy Faith, are all part of the Murakami soundtrack.) Like others in the book Kino has become a man without a woman, but one incapable of realizing what’s missing in his life. Not a unique perspective, but Murakami’s ability to both politicize and poeticize the bartender’s mindset makes “Kino” something simultaneously other-worldly and a mirror of our own closed-down time. Other characters deny the importance of love and learn too late what havoc they invite, mostly to themselves.

Murakami has described “The Great Gatsby” as “the most important novel of my life,” even translating F. Scott Fitzgerald into Japanese. (Philip Gabriel and Ted Goosen do the honors, soulfully, in translating Murakami into English.) There’s a Nick-Gatsby-like relationship between many of the characters in “Men Without Women,” the narrator often living along the straight and narrow, his friend or guru living more on the edges, taking risks and bending rules.

“Women,” laments one of the more tragic characters in the collection, “are all born with a special, independent organ that allows them to lie … But without the intervention of that independent organ — the kind that elevates us to new heights, thrusts us down to the depths, throws our minds into chaos, reveals beautiful illusions, and sometimes even draws us to death — our lives would be indifferent and brusque.”

Murakami takes an anthropological look at the species. “Samsa in Love” has Kafka’s cockroach turn back into a human being, but one that can’t wrap its insignificant two arms around what it means to be human. Samsa recognizes early on that men without women, at least straight men without women, are a sorry lot.

Murakami says of a shut-in who’s visited by a government-supplied aide, who tends to his client's every need: "What his time spent with women offered was the opportunity to be embraced by reality, on the one hand, while negating it entirely on the other.”

It’s not a bad description of how Murakami both embraces and negates the everyday world, a world in which Percy Faith is both elevator music — and music of the spheres.