Advertisement

How Mass. Is Faring In Its Emissions Reduction Goals

It's official: Last year was the hottest on record for the planet, and the long-term forecast for New England, according to a new draft federal report, calls for a lot warmer temperatures, much higher seas and more precipitation.

The release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, from the burning of fossil fuels, is disrupting the world's climate. But Massachusetts is trying to fight back.

On Friday, the Baker administration released a new regulatory road map designed to guide the state to meet ambitious cuts in climate-changing emissions.

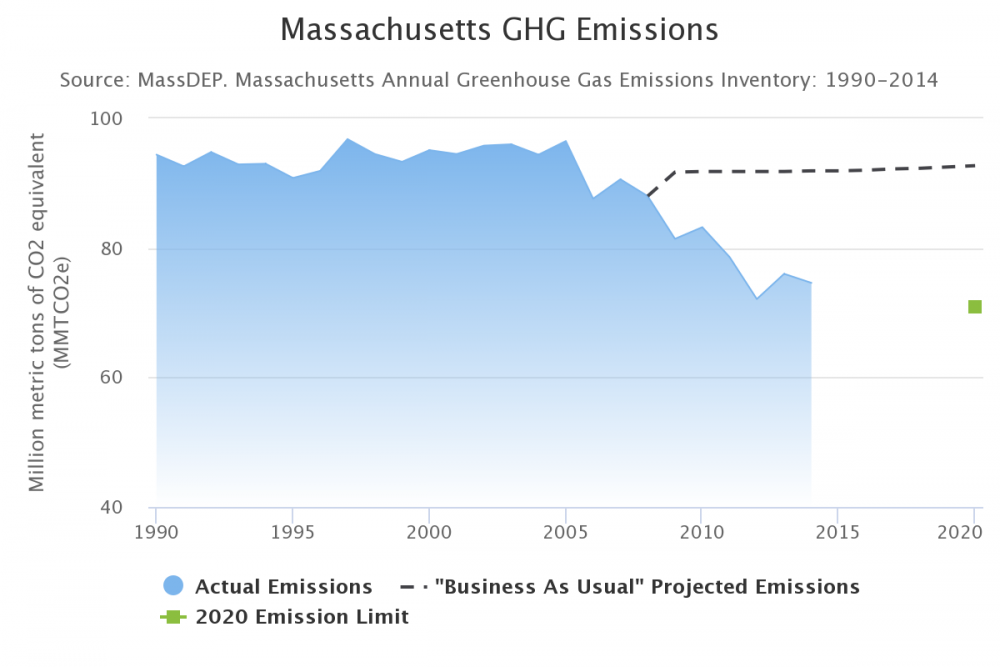

Massachusetts was one of the first states to take action to reduce emissions. The 2008 Global Warming Solutions Act (GWSA) requires Massachusetts to cut emissions 25 percent statewide from 1990 levels by 2020 -- and 80 percent by 2050.

"If we miss these targets then we're heading into uncharted waters," said David Ismay, a senior staff attorney with the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF).

Ismay says the future emissions targets are based on the best available science to prevent a worst case scenario.

"We could have as much as 10 feet of sea level rise here in Massachusetts by 2100 if we don't start changing the way we power our economy," he said.

Last year the CLF sued the state and won over the intent and wording of the GWSA. In a unanimous landmark decision, the Supreme Judicial Court ruled the state's programs to cut carbon were insufficient, and it ordered the Baker administration to set annual declining limits on greenhouse gas emissions for individual sectors of the economy: agriculture, transportation, residential and commercial heat and light and electric generation.

"I think people will look back and see the case and these regulations as the beginning of the kind of transformative action that we need in the next 30 years," Ismay said.

But with three years to go to meet the first target of a 25 percent reduction in emissions, the state is at 21 percent.

That figure is two years old, but the best available, says state Secretary of Energy and Environmental Affairs Matthew Beaton, who is optimistic the new regulations will close the gap and meet the mandated target.

"As it's trending right now," Beaton said Thursday, "we feel as though we have enough confidence in our numbers, the modeling numbers, the assumptions that we made, and the conservative nature that we will be over and above the goal of 25 percent."

There are six new regulations. Most are small or symbolic; two account for most of the gains: Electric generators will have to reduce the amount of carbon they emit into the atmosphere, and utilities will be required to buy more clean energy.

State officials praised the Conservation Law Foundation for working with the administration to come up with the regulations, but CLF attorney Ismay says they don't go far enough.

Advertisement

"I joke it's like going from smoking two packs of cigarettes a day to one and still thinking you are doing something good for your health," he said. "What we need now is to convert to renewable generation."

Dan Dolan, though, has concerns. "Our concern is that the regulations that are being proposed are akin to taking a sledgehammer to kill a fly," he said.

Dolan is actually a big supporter of renewable power. As president of the New England Power Generators Association, he represents most of the large wind and solar producers in the region, as well as those that use fossil fuels, hydro and nuclear energy.

"We need to regulate carbon emissions," he said. "The question is how, and to what degree."

He says power generators that burn fossil fuels have done the most to meet the 2020 goal.

"And what we've seen from the power plant side, since 1990, a 60 percent reduction in carbon emissions from power plants in Massachusetts," Dolan said. "Power plants have reduced almost twice the amount of [emissions than] any other sector of the economy."

Much of that comes from closing coal- and oil-burning plants that emitted a lot of carbon. The last coal plant in the state shut down earlier this year.

Today, 42 percent of Massachusetts' electricity comes from in-state power plants that burn natural gas. Dolan estimates that 90 percent of the Baker administration's new plan to meet 2020 targets would come from reducing emissions from those plants.

Dolan says not only is that unfair, it doesn't make sense, because to meet the state's demand for electricity will require getting more power from out of state.

"Those other plants, when they run they emit at a higher rate than Massachusetts plants, and we will end up with higher regional emissions and more expensive electricity," he said.

State officials estimate the average consumer's electric bill will increase 1 or 2 percent a year.

To meet the need for clean energy, last year Baker signed a law requiring utilities to procure more electricity from carbon-free wind, hydro and energy storage systems. It's the largest green power procurement in state history. Winning bidders will get 20-year contracts. But building transmission lines and wind farms is at least five years or more into the future.

"It's exciting what will take place in the future," said state Sen. Marc Pacheco, a Democrat from Taunton who led the effort to pass the Global Warming Solutions Act. He is reviewing the administration's regulations to meet the 2020 goal, and has proposed legislation to set interim targets for 2030 and 2040.

Pacheco sees wind, hydro and storage as the way to power the Massachusetts economy.

"I don't think we need more fossil fuels," he said. "It's time to embrace an energy the fuel source of which costs us nothing."

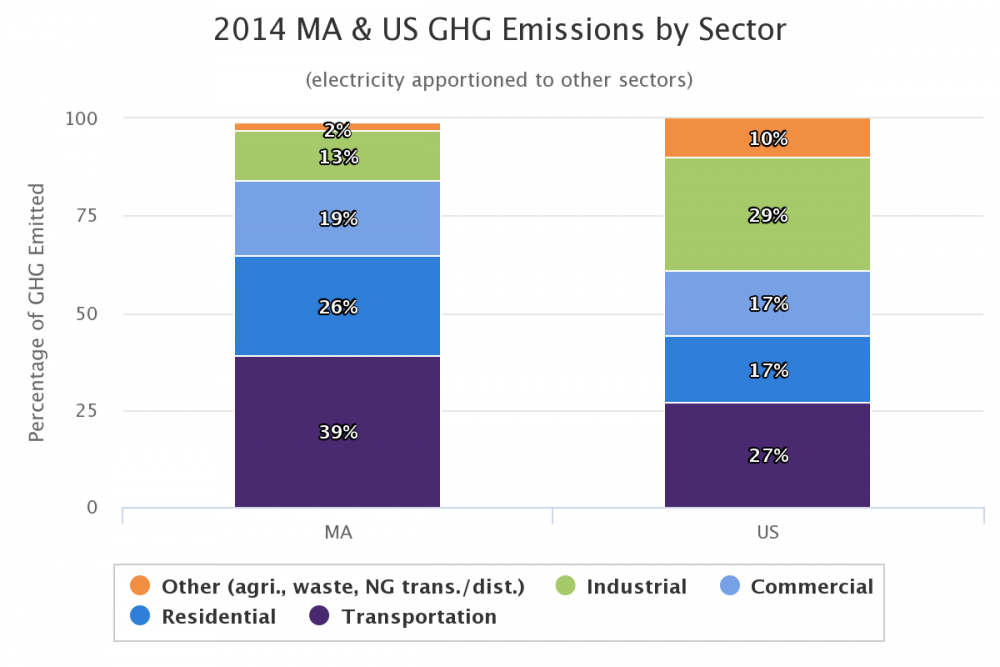

From 1990 to 2014, Massachusetts gross domestic product grew 70 percent, while climate-warming emissions declined 21 percent. But to stay on the road to a clean energy future will require cracking the toughest dirty energy source: transportation. Over that same period of time there's been virtually no reduction in carbon emissions from vehicles.

"The transportation sector is one of the most difficult emission sources to decarbonize because it's so decentralized," said attorney Megan Herzog, who's also with the CLF.

Herzog says today, cars and trucks — not power plants -- are the No. 1 source of climate pollution. Drivers — you and I — are responsible for emitting about 40 percent of the state's greenhouse gases.

Baker's plan to meet the 2020 reduction targets includes a regulation requiring state agencies buy low- and no-emission vehicles, but admittedly, that's largely as a symbolic act. Herzog says aggressive action on transportation is needed.

"If we have our eye on the prize of reducing emissions by 80 percent by 2050, there's no way we're going to get there without a serious aggressive transition of transportation away from petroleum-based fuels," she said. "There's just no other way to get there."

That means electric vehicles. Herzog believes they'll soon catch on as quickly as smartphones. Today, out of 4.7 million vehicles registered in the state, just 11,000 are EVs. State officials estimate that will increase to 300,000 by 2025.

And where will all that electricity to power vehicles come from? Sen. Pacheco says it will be New England, homemade energy — captured from the sun, wind and water.

"Instead of being at the end of the pipeline we'd be at the beginning of a whole new world of energy transmission," he said. "Now wouldn't that be great?"

Cause for optimism, but damage has been done, the climate already disrupted.

So Baker has directed the state to work with cities and towns across Massachusetts to assess vulnerability and build resiliency to address the effects of global climate change.

This article was originally published on August 11, 2017.

This segment aired on August 11, 2017.