Advertisement

At MIT, It's Out With The Old Case Studies, In With Immersive Ones

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology's leading role in online education for all is changing how its own faculty approach more traditional education.

For example, at the MIT Center for Real Estate, professors are rethinking the case study approach common in management training.

The change stems from an effort to introduce case studies to MIT's "Massive Open Online Courses," better known as MOOCs.

"Of course, the classic case study, it's a PDF file, about 15 to 20 pages," says the center's director, Albert Saiz. "It's very difficult to implement in an online class. Attention spans of students, especially younger students, are getting shorter."

So Saiz led a team that developed case studies designed to more easily hold the attention of big audiences.

"The cases that we're producing are multimedia," Saiz says. "They use videos. They use sound. They use spreadsheets. They use photos. They also use games."

Saiz says a goal of the presentations is to more thoroughly plunge students in business challenges.

"We are really trying to immerse the student into the architectural and the visual reality in which people are doing their business, so it was very important for us for the case to be visual, to be beautiful," Saiz says.

"In one of the cases," he adds, "based in Panama, one of the tenants of our entrepreneur is actually someone who sings and composes music, so we have the music of one of the persons in that community who is actually coming from a background of poverty, and this individual used to be a member of a gang."

"I had grown up in Miami, and it kind of went through a revitalization while I lived there," says developer KC Hardin in an interview included in the immersive materials. (Here's a link to a beta version of the Panama case, for desktop/laptop, and best viewed in the Chrome browser.)

Hardin wanted to make sure that gentrification did not drive out the old-timers who contribute to the neighborhood's character.

Advertisement

"That revitalization period created a lot of great things, but it also displaced a lot of people and tended towards this cultural homogenization, where things got very commercial," Hardin says. "Everything that drew you to the place would eventually be destroyed."

Students learn that Hardin was determined not to make that mistake in Panama.

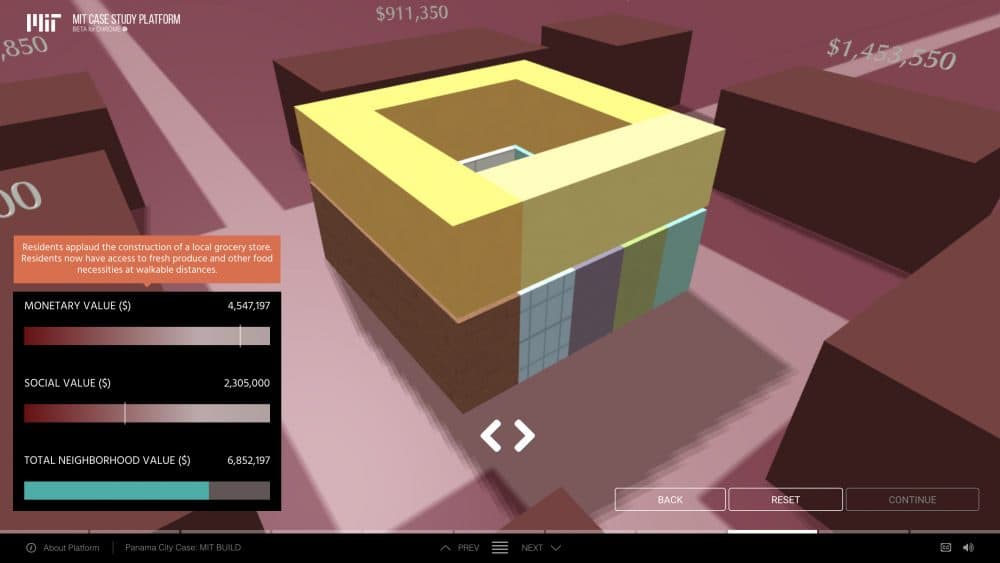

The case studies include games.

"In one of them, for instance, you have a building and you have to choose what is the mix of uses in that building," Saiz says. "You have a residential part and a commercial part, and you can decide to make the residential part all high-income, all low-income. If you make it all about high-income residents, it's a problem because the neighbors are not necessarily going to be friendly."

MIT sees these immersive case studies as a brand-new tool.

"That is between an academic paper, a website and a documentary film, and we don't see anything like it that's ever been created before," says Danya Sherman, who's manager of the MIT Case Study Initiative.

Sherman says teams have filmed in Panama, Mexico City, Florida and Malaysia.

"We really want students to feel like they're on the ground with us, investigating with us what is going on in a particular place and what led to those outcomes and asking questions of us, too, like, who did we not interview that maybe we should have?" Sherman says.

The Malaysia case study is part of professor Lawrence Susskind's open online course on socially responsible development.

Susskind is teaching another MOOC, on entrepreneurial negotiation. In that course, students across the world see one another on an MIT platform, then compare themselves to other teams. Susskind expects this to become the first online course MIT students can take for credit.

"We've gotten away, in the university, with standing behind a lectern and reading from notes for too long," Susskind says. "You can't do that. And what's interesting is that once you do it for the MOOC, you feel like a jerk when you go back to a regular class and you haven't put something together to supplement what you're doing in the front of the class, because people will demand it."

MIT pioneered MOOCs, allowing people all over the world to take MIT courses. Now the MOOCs are prompting a transformation of courses on MIT's own campus.

This segment aired on January 8, 2018.