Advertisement

Review

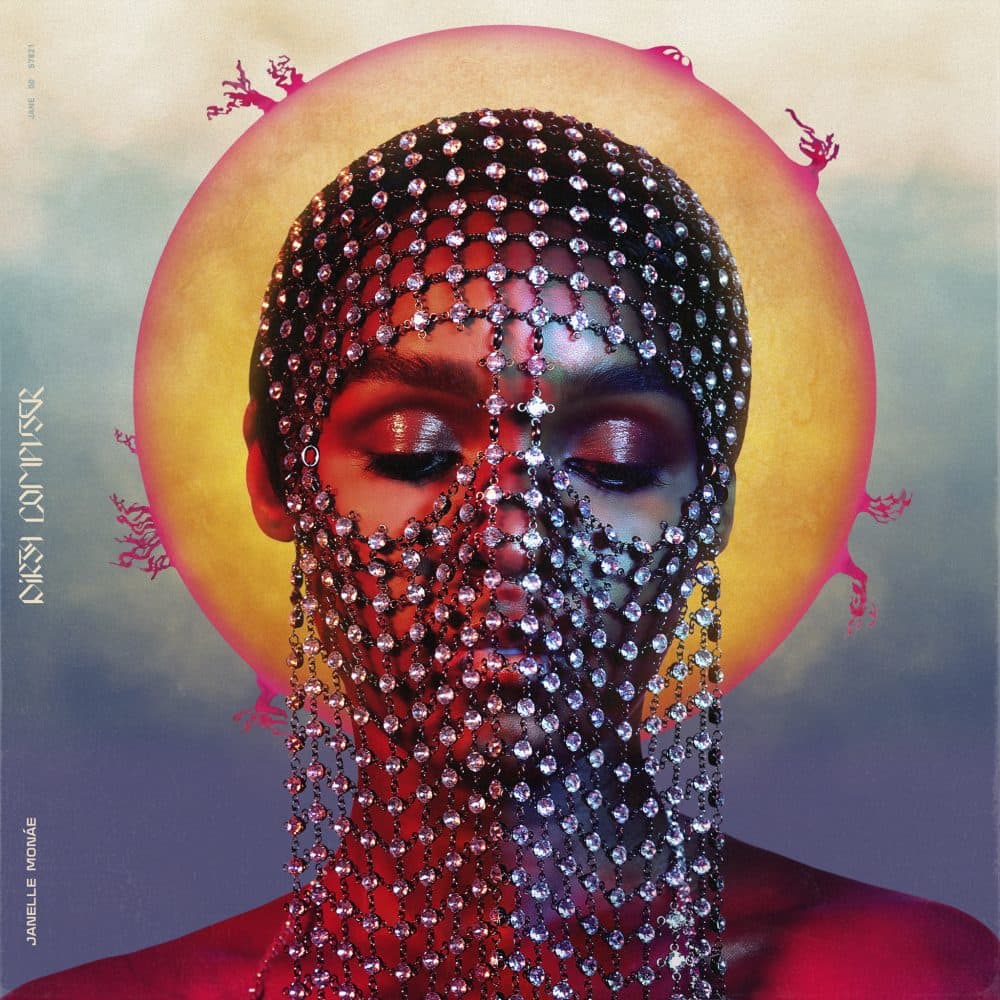

On 'Dirty Computer,' Janelle Monáe Reveals Herself, Sort Of

In the breathless buildup to Janelle Monáe’s long-awaited third album “Dirty Computer,” a narrative took hold. “Janelle Monáe Frees Herself,” trumpeted a headline in Rolling Stone. A New York Times Magazine cover story promised to reveal “How Janelle Monáe Found Her Voice,” declaring the pop star “ready to step into a more authentic self.”

It was a smart angle to push, given that “Dirty Computer” is the first of Monáe’s projects to dispense with her alter ego Cindi Mayweather, an android from a fictional dystopia where relations between humans and cyborgs are forbidden. The conceit allowed Monáe to speak equally to black and queer liberation, while the music’s funky futurism spurred the R&B rebirth lately taken up by artists like Solange and SZA. Monáe’s trademark pompadour and tuxedo telegraphed a hip, androgynous sensibility that earned her a significant LGBT following. But the singer remained coy about her own sexuality and tight-lipped about her personal life. For years, she would say only that she dated other androids.

So when Monáe released the music video for her innuendo-soaked single “Pynk,” which depicted her canoodling with the actor (and Monáe's rumored girlfriend) Tessa Thompson, it seemed the long-anticipated coming-out was at hand. At the 11th hour, Monáe delivered, describing herself in an interview with Rolling Stone as a “queer black woman” and announcing an affinity for pansexuality. Queer Twitter let out a collective cheer.

“Dirty Computer” and its accompanying “emotion picture” — aka long-form music video — dropped on Friday. As promised, the album deals more overtly with real-world issues, and it is possible to detect a personal bent in some of the lyrics. But, as its accompanying visuals reveal, the Monáe of “Dirty Computer” did not so much “step into a more authentic self” as trade one avatar for another — instead of the cyborg messiah Cindi Mayweather, now she is Jane 57821, a bisexual party girl on the run from the law.

In the nightmarish future depicted in “Dirty Computer,” a tyrannical government keeps its subjects brainwashed and in line by erasing “dirty” memories from their minds, the way you might delete photos from a hard drive. Jane runs with a pack of model-hot, fashionably eccentric young people who do counter-cultural things like throw a rave in an empty swimming pool and get in trouble with the cops, though precisely what it is that makes someone a target in this universe is less clear — a weird haircut, possibly, or being one-third of a ménage with the luminous Thompson and a man who is as handsome as he is unmemorable. It may even be the act of falling in love itself.

It is along these lines that a bifurcation between the music and imagery of “Dirty Computer” occurs. On the album, Monáe takes aim at the injustices particular to America, unpacking, for example, the radically different ways in which the world reacts to white and black rebelliousness on the defiant “Crazy, Classic, Life,” or calling out the gender wage gap in the synth-flecked “Americans.” These particularities are largely absent from the film’s plot, however; in place of systemic inequality and injustice, it is difference, broadly defined, that puts its hero at risk in a conformity-obsessed society. On Monáe’s two previous albums, such high-concept, metaphor-heavy narratives proved flexible, yielding a plethora of possible analogs, from slavery to interracial relationships to queer identity. “Dirty Computer” has its moments of eerie resonance with reality, most notably in the way in which its (black) protagonists are targeted by the police and constantly surveilled. But in general, the fantastical setting of “Dirty Computer” has the unfortunate effect of flattening some of the more pointed critiques of its lyrics. In the film’s dreamy, hyper-modern milieu, feminism and black pride become aesthetic signifiers, reduced to feel-good slogans and hashtags.

Advertisement

The visual and sonic strands of “Dirty Computer” do sometimes manage to operate symbiotically, especially in the album’s exploration of pleasure. This is where Monáe locates power and resistance, and where she makes her strongest case for the project. “Dirty Computer” is ecstatically gorgeous to look at, its imagery at once rigorous and sensual, all clean geometry and pastel hues. “Let’s get screwed/ I don’t care/ You fucked it all up now, we’ll fuck it all back down,” Monáe sings in “Screwed,” a lean, sparkly electro-pop jam that may as well be a thesis statement for the album. A snarling coda imbues what would otherwise be a nihilistic kiss-off with revolutionary spirit, the song’s flippant, sugar-coated hook — “Let’s get screwed!” — transformed into a battle cry.

“Dirty Computer” is Monáe’s most transparent bid for commercial success, and it eschews the prog-rock ambition that made previous efforts occasionally too busy and sometimes sublime. The influence of Prince, one of Monáe's earliest champions, can be felt throughout, from wiry guitar licks and hip-swiveling rhythms to homages that border on outright mimicry. It is, for the most part, supremely appealing music, and Monáe shines in her newly stripped-down, yet salient, surroundings.

Monáe was a key innovator in the new wave of progressive R&B, mishmashing funk, stadium rock and dance pop with Afrofuturist imagery and ideas. But it has been five years since the release of her sophomore album “The Electric Lady,” and “Dirty Computer” sees the musician striving to stay abreast of the curve. Monáe mostly succeeds in her mission to fuse throwback grooves with of-the-moment sounds — trap’s lithe bass lines and skittering hi-hats prove a surprisingly good fit with the shivery, up-tempo bops that form the backbone of “Dirty Computer.” Yet the album stumbles sometimes in its desire to make you sing along; on songs like “Crazy, Classic, Life” and “Pynk,” the buoyant sweetness of a light-on-its-feet verse sags under the weight of a rote, overly-engineered hook. Monáe thrives in the ascent, but hasn’t quite mastered the release.

But oh, that ascent. The feeling that “Dirty Computer” captures most deftly is one of yearning, of desires not quite realized and the peculiar euphoria they contain. “Dirty Computer” is not the diaristic tell-all that fans might have hoped for based on the lead-up to its release; when intimacy allows itself to be glimpsed, it is with a cautious, sidelong glance. “I just want to paint your toes and in the morning kiss your nose,” Monáe intones in the extended version of “Pynk” that appears in the film. Bare-legged, ensconced in a magenta sweater, she kneels upon a mattress in a rose-tinted desert, knee to knee with Thompson. They gaze at one another, Monáe reaching up to caress the tip of the other’s nose, before moving abruptly into a choreographed duet that grazes slyly against the contours of anything too explicit. This is a classic Monáe move, more flirtatious feint than declaration of love. But it is in such shy, tender moments that the Monáe of “Dirty Computer” also feels the closest.