Advertisement

Century-Old TB Vaccine Shows Promise Against Type 1 Diabetes, MGH Research Finds

A new study finds that an inexpensive vaccine used globally to prevent tuberculosis may help treat Type 1 diabetes — if given time to kick in.

Six years after publishing phase 1 clinical trial results, which did not show clinical benefit, Massachusetts General Hospital researchers report promising follow-up data, collected over eight years after the initial trial.

The long-term data suggests the vaccine, the 110-year-old Bacille Calmette-Guerin, or BCG, does lower blood sugar in people with Type 1 diabetes — but it takes a few years to see that effect.

Three years after getting two doses of BCG, all nine patients with Type 1 diabetes given the vaccine saw their blood sugar fall to the “near-normal” range, the MGH researchers report. (For those well-versed in diabetes, their average blood-sugar measure HbA1c fell to 6.65 percent, just above the diabetic cutoff of 6.5 percent.) And this significant drop lasted: It was sustained over the next five years of follow-up monitoring, they report.

The delayed onset of positive effects seen in this study mimics the findings of other BCG clinical trials for autoimmune diseases like Type 1 diabetes, such as multiple sclerosis, said Dr. Denise Faustman, director of the MGH Immunobiology Laboratory and senior author of the study.

In fact, it was the peculiar delayed results of a BCG study from Italy that prompted the MGH team members to revisit their own study. “The secret of [those] trials was that the drug took a while to kick in,” she said. “That gave us a pretty good clue that the time course for this drug […] was different than we originally knew.”

The results, released Thursday in the journal npj Vaccines, add hope that the inexpensive vaccine could become an effective addition to Type 1 diabetes treatment regimens. More than a million Americans have Type 1 diabetes, and the quest for a cure has faced a history of challenges, including the mixed results of previous BCG studies in children with Type 1 diabetes.

Advertisement

“It’s a very exciting concept,” said Dr. Joseph Bellanti, professor of pediatrics and microbiology-immunology (emeritus) at Georgetown Medical Center in Washington, D.C., who was not involved with the study. “But it has generated some controversy” among the metabolism scientific community because of its “very striking positive results.”

“My take on it is that the study represents a very significant contribution,” he said, adding that since these results come from a “well-planned, well-powered randomized clinical trial,” they are more definitive than previous BCG studies.

Overall, Bellanti said, he's “cautiously optimistic.”

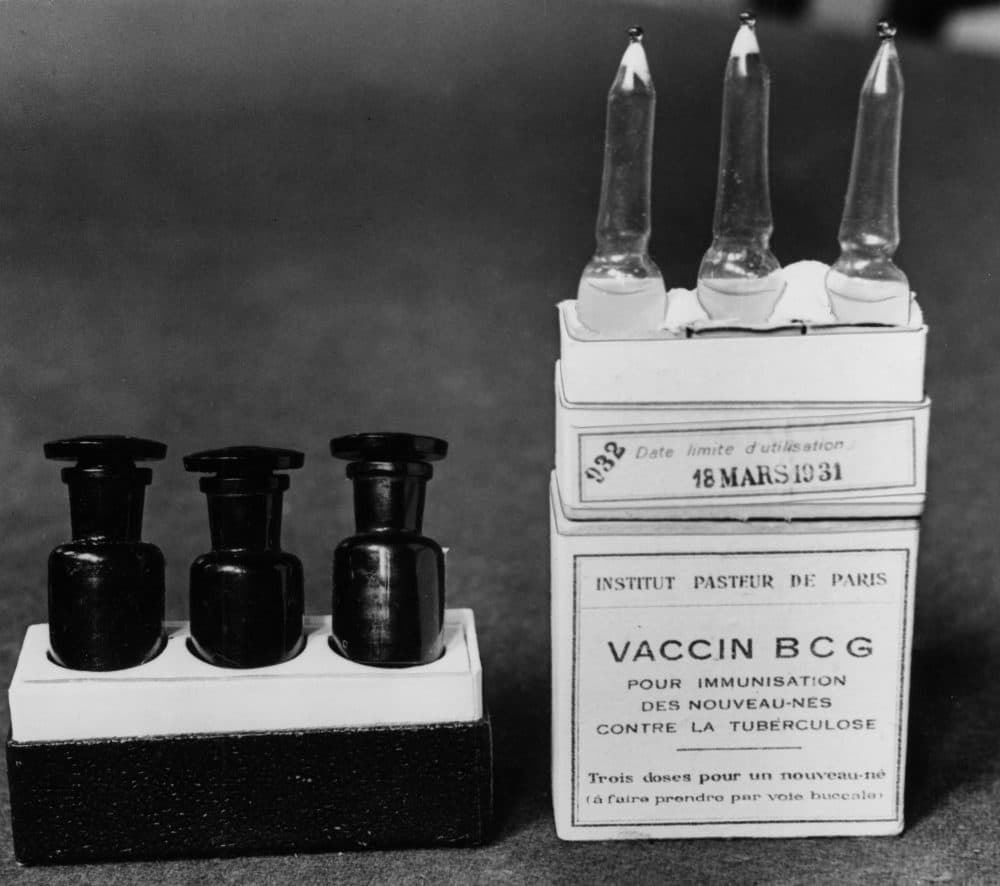

The Bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine, named after its two French creators Albert Calmette and Camille Guerin, was first used in humans in 1921, after years of animal testing and development.

According to the World Health Organization, the vaccine has a well-established safety record, and experts estimate it’s been given to more than 4 billion people worldwide.

However, due to the low risk of TB in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the BCG vaccine only for those at high risk of TB exposure. Faustman's lab is currently conducting multiple clinical trials on the vaccine's secondary effects on Type 1 diabetes.

And as for the years-long delay in clinical response, Faustman says phase 2 trials — which are currently underway — are exploring whether more BCG injections could shorten the period between injection and results. “It may or may not [work], we’ll just have to see,” she said.

Alongside their trial results, the MGH researchers report a “novel metabolic method” that may explain just how BCG combats Type 1 diabetes.

“We’ve discovered a new way this organism can lower blood sugar, that’s not because of insulin [or] a change in insulin resistance,” Faustman said.

Unlike her lab’s previous findings in mice, regeneration of insulin-producing pancreatic cells was not the main contributor to blood sugar reduction in the diabetic human subjects. While that was a “tiny component,” she said, it could not explain the dramatic drops in HbA1c seen in the trial. Instead, the answer appears to lie in the vaccine’s TB origins.

“[TB] changes the metabolism, and it eats sugar for its energy source,” Faustman explained. When BCG is administered to people with Type 1 diabetes, defensive white blood cells called lymphocytes gain an increased taste for sugar too; they switch their normal energy consumption habits to a process called aerobic glycolysis, which allows them to “eat more sugar for energy.”

Their increased cellular appetite means “sugar goes down, and they stop transporting it,” ultimately resulting in a significant and sustained drop in blood sugar, she said.