Advertisement

Commentary

Leonard Bernstein's Centennial Proves His Greatness As A Composer

When Leonard Bernstein was appointed music director of the New York Philharmonic in 1958 he was hailed as America’s first maestro. Four years earlier, he had held a large part of the nation spellbound on CBS’ “Omnibus” with his absorbing analysis of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. And with his full embrace of television, he not only became the country’s foremost music educator, but demonstrated what an electrifying conductor he was as well.

All that has been widely agreed on for decades. What is becoming more evident in 2018, in the midst of his centennial celebration, is his greatness as a composer. Of all the accolades that have been thrown his way this year, nothing would have pleased him more than to see his compositions gain in stature.

I’d go further and say that the Lawrence-born and Boston-bred Bernstein was the greatest composer we’ve seen since the iconic modernists of the early to mid 20th century — Stravinsky, Bartók and Shostakovich. This is heresy to “serious music” mavens, particularly those whose tastes run to the atonal and 12-tone, but with the recent spate of CDs, DVDs, concerts and books, it’s evident that Bernstein’s eclectic approach to music set a standard for how many of us listen to music today — without boundaries or strict definitions. It’s also how a growing number of composers, from Nico Muhly to Vijay Iyer, see their own writing, in which rock, jazz and classical feed off and inform each other.

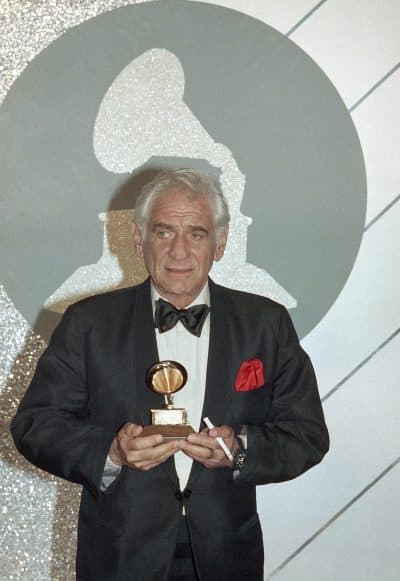

Bernstein’s speech at the 1985 Grammys, where he was given a Lifetime Achievement Award, sums up that eclecticism:

"I am very happy tonight for music. And I’ll be even happier and maybe even ecstatic if tonight can be a step toward the ultimate marriage of all kinds of music, because they are all one. There is only good music and there is bad."

Bernstein, himself, struggled to live up to that credo. He hoped to write the great piece of “serious music” that would put him in company with the Stravinskys of musical history.

But he was already there.

Take a look at his musicals and operas. If you think of them as all one entity — not as musical theater, but music for theater — then who in the 20th and 21st century has a body of work that could compare to “West Side Story,” “Candide,” “On the Town,” “Wonderful Town,” “Trouble in Tahiti,” the ballets “Dybbuk” and “Fancy Free,” “Songfest,” “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue,” “Mass,” “A Quiet Place” and the lovely if little-known “Peter Pan.”

If you break those pieces down along traditional genre lines, it’s easy to dismiss Bernstein. Igor Stravinsky reportedly disliked “West Side Story”; it probably wasn’t much more classical in his mind than “The Music Man.” No bopper would think that any of Bernstein’s work was bluesy enough to qualify as memorable jazz. As a rock ‘n’ roller in the ‘70s, I had no interest in my roommate’s copy of “Mass.”

Advertisement

But put aside genre definitions and a portrait of real musical genius emerges. Like others before and after him, Bernstein incorporated a variety of musical forms and emerged with a body of work that bounds with passion, warmth, spirit, spirituality, loneliness, doubt and rebellion. His determination not to give in to despair could lead him toward cliché in his lyrics, as in his Third Symphony, but the music always had a more sophisticated answer to the way we live our lives today.

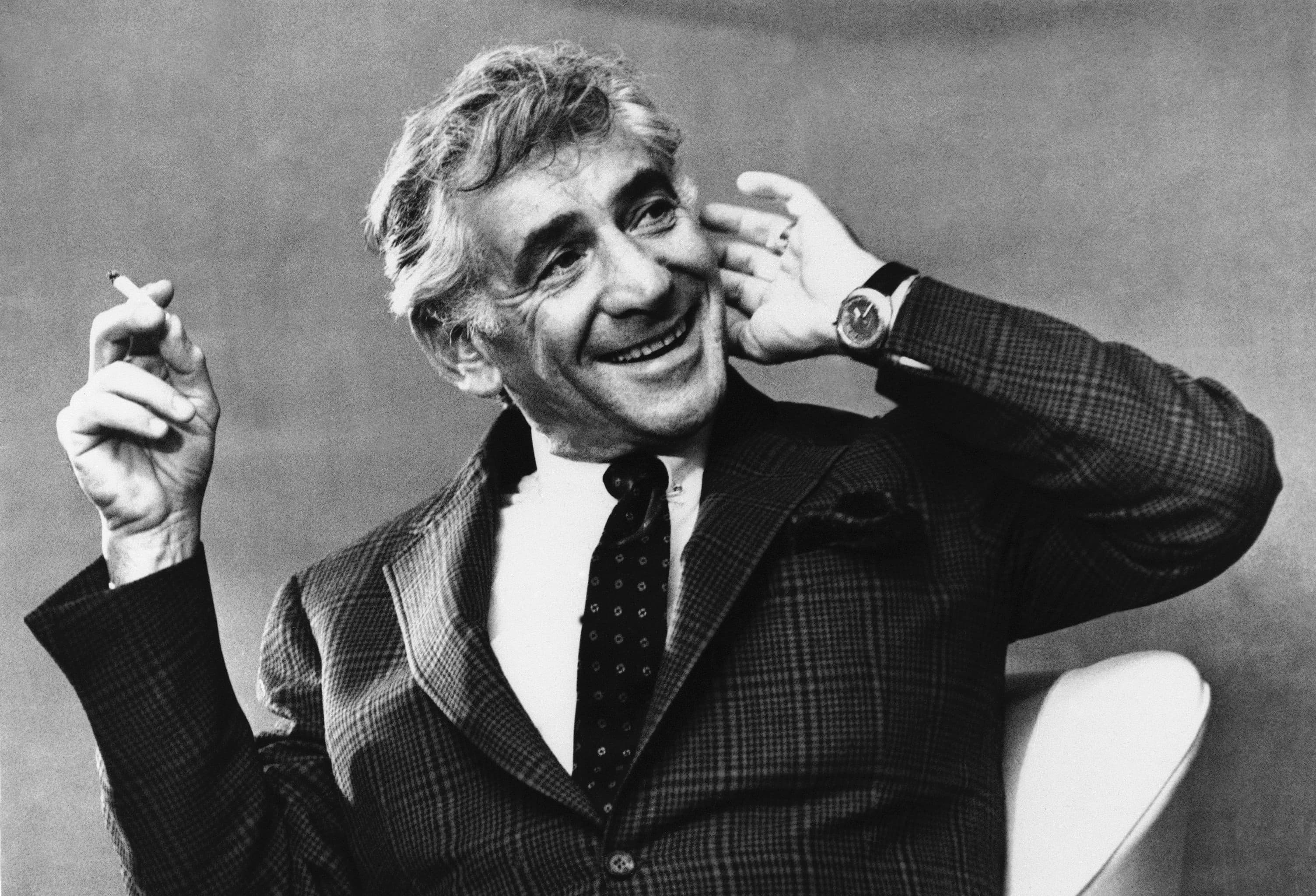

“The dynamic energy of the universe? It emanated from one man holding a cigarette and a glass of Scotch.”

Charlie Harmon, Bernstein's assistant between 1982 and 1985

It’s worth quoting Allen Shawn, author of 2014’s “Leonard Bernstein, An American Musician” at some length in terms of the complexity sophistication of that music. Here he’s talking about “West Side Story”:

“The music is almost Beethovenian in its reliance on a few motives and interval combinations to unify its heterogeneous sections. The story handed Bernstein an opportunity to revel in two idioms that were second nature to him: Latin American music for the Puerto Rican immigrants and a bebob-tinged jazz for the ‘self-styled "Americans" ’ (Bernstein’s words), all the while encouraging him to explore his aspiration to an operatic language derived from musical theater … a variant of the shofar’s call to worship introduces the piece … Where other composers can be noted as influences [particularly Stravinsky] the influences evaporate; nothing could sound more like midcentury, urban America. The score has vocal sections of operatic complexity and substance, most notably the ‘Tonight’ ensemble.”

He also quotes Kenneth Tynan’s putting-it-all-together description of “West Side Story”: “It sounds as if Puccini and Stravinsky had gone on a roller-coaster ride into the precincts of modern jazz.”

While Shawn’s superb analysis can be extended to Bernstein’s other works for the Broadway stage, particularly “Candide,” one can easily reverse the process for works usually described as “classical,” particularly the jazziness of his symphonies and orchestral pieces like “Prelude, Fugue and Riffs” or the almost pop-song lyricism in parts of “Serenade” and “Chichester Psalms.” And it becomes more apparent with every passing year that his one-act opera, “Trouble in Tahiti,” and his more controversial “Mass” are as good as music for the theater gets. Ditto for his one foray into composing for film, “On the Waterfront.”

"Nothing could sound more like midcentury, uban America than 'West Side Story.' The score has vocal sections of operatic complexity and substance, most notably the ‘Tonight’ ensemble.”

Allen Shawn

Bernstein, himself, struggled with thinking that he needed to do something more traditionally operatic than “Trouble in Tahiti,” which resulted in his final major work, “A Quiet Place.” His assistant Charlie Harmon chronicles his struggles with the piece in “On the Road & Off the Record with Leonard Bernstein: My Years with the Exasperating Genius.” It deals with the years 1982 to 1985, while Bernstein was on whirlwind tours and trying to finish the opera. These were also years that his body couldn’t keep up with his spirit and the booze, pills and tobacco were taking a terrible toll. For all the threesomes and crotch-grabbing detailed in the book, Harmon has a clear-eyed view of Bernstein’s status as conductor and composer. After Bernstein stayed up for an all-night party to witness an astronomical convergence, Harmon suggests he look to himself rather than the stars: “The dynamic energy of the universe? It emanated from one man holding a cigarette and a glass of Scotch.”

The best example of Bernstein’s all-around gifts as a composer is the “Complete Works” on Deutsche Grammophon, conducted when possible by the man himself. With 26 CDs and three DVDs, it’s a pretty daunting introduction to his work. But as the symphonies blend into the musicals, as the ballet “Dybbuk” leads into Michael Tilson Thomas culling the best music of “A Quiet Place” into an orchestral suite, as the lyricism of “Peter Pan” morphs into his operatic masterpiece, “Trouble in Tahiti,” it becomes evident that there was one musical language that transcended genre in all his work. And even though the original versions of “West Side Story” and “Candide” are superior to the operatic versions in this collection, the orchestral playing on the DG versions are out of this world and do a better job of squaring the circle with his other writing.

Pianist Leann Osterkamp puts a one-person show together of Bernstein’s musical language on the two-CD complete keyboard works on the Steinway & Sons label, one of a number of excellent solo piano CDs released this year. Listening to her mixing and matching the anniversaries Bernstein wrote for his friends with Judaica and works that would later turn up in musicals and symphonies again demonstrates how his writing transcended genre without sacrificing anything in the way of sophistication. It's like listening to a great jazz pianist riffing on his or her compositions.

Listen to what Osterkamp and Michael Barrett do with collaborators Adolph Green and Betty Comden's "Just in Time," the first part of the "Bridal Suite" that Bernstein wrote for Green's marriage to Phyllis Newman in 1960:

Bernstein was also renowned for his mentorship of young conductors at Tanglewood and elsewhere. Many, like Tilson Thomas and Kent Nagano, have rewarded him by carrying on his compositional legacy with terrific Bernstein recordings of their own.

And let’s not forget Marin Alsop’s eight-CD Naxos collection. Alsop has been as important a figure for American women as Bernstein was for men, and was in fact mentored by him at Tanglewood. She is so at home with Lenny that many critics think she does a better job with his music than he did himself. I wouldn’t go that far in general, though these are the best recordings of “Mass” (thanks in large part to the aptly-named Jubilant Sykes as the Celebrant) and his problematic Symphony No. 3 (thanks to Claire Bloom toning down the melodramatic narration that Bernstein twice recorded, once with his wife Felicia Montealegre).

Written for the inauguration of the John F. Kennedy Center in Washington D.C., “Mass” was widely dismissed at the time as too polyglot. Today it stands as testimony to Bernstein’s musical vision. Here the electricity of “West Side Story” meets the political wrath about Vietnam and the personal and philosophical wrath about the silence of God. It isn’t rock and it isn’t Broadway music and it isn’t classical, but it is great music that incorporates all of his passions.

The whole video is worth watching, but Alsop and Bernstein are together around 1:50:

"Mass" is hardly without cliché. The purpleness of Bernstein's prose was often embarrassing, particularly in Symphony No. 3. And even though Stephen Wadsworth had writing credit for the opera, “A Quiet Place,” Bernstein has to take a significant part of the blame for just how trite that libretto is.

Yet there is beautiful music underneath as the Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra, which Bernstein loved conducting, demonstrated this summer. The Boston Symphony Orchestra and the Pops went all in on Lenny both in Boston and in Lenox. They repeated the show I saw a couple of years ago, their magnificent accompaniment to “West Side Story” that twinned beautifully with Barrington Stage Company’s leaner and meaner, though no less mightier, production of the musical in Pittsfield (through Sept. 1). The Knights' staging of "Candide" at Tanglewood was a ton of fun. (I'm sorry I missed the Pops' acclaimed staging of "On the Town.")

Bernstein loved conducting at Tanglewood. (Unfortunately, a set of Bernstein at Tanglewood CDs fell through, according to the Bernstein office.) His concerts were always events and the BSO returned the favor by playing most of his orchestral music (except the complete “Mass”) accompanied by everyone from Yo-Yo Ma to the Boston Ballet.

It all comes to an end on Saturday with a gala concert featuring Ma, Audra McDonald, Midori and BSO and Pops conductors, past and present. Hopefully that will be the coda that, like the BSO and Tanglewood seasons, bring all the facets of Bernstein’s compositional skills together.

George Steel, the curator of music at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and a former aide to Bernstein, picks up the baton, at least figuratively, in September. Almost all the concerts this fall will feature something by the composer as part of “In Boston, It’s Bernstein.” I’m particularly looking forward to the Claremont Trio performing his trio Nov. 11, written when he was attending Harvard at the ripe old age of 19.

One of the great delights of the summer has been his daughter, Jamie Bernstein’s “Famous Father Girl: A Memoir of Growing Up Bernstein.” Amid the childhood joys, the traumatic teens, the striving to find herself, the father’s drift from his wife to gay men, and his late-life dissolution, there is an astute analysis of her father’s musical gifts, and his flaws.

As composer, conductor, teacher and overall presence, Bernstein captured what it meant to be fully alive in the second half of the 20th century. Personally speaking, he showed what it meant to embrace American assimilation and ethnic pride in almost equal measure. Musical notes were not just notes but guideposts for how to live a life, particularly life to the left of center.

That’s all in the music, too. As Jamie Bernstein says toward the end of the book:

“The notes he strung together are as uniquely, identifiably him as a fingerprint. We listen to the wrenching violin solo in the slow movement of ‘Serenade,’ the rollicking ‘Profanation’ from the ‘Jeremiah’ Symphony, or the jagged, propulsive ‘Rumble’ from ‘West Side Story,’ and there he is — in all his tenderness, his raunchiness, his intellectual panache, his agonizing over God, his despair over humanity, his cautious but dogged hope that we’re all getting somewhere.”

It’s all there, in all his music.