Advertisement

'Freshwater' Writer Akwaeke Emezi Reclaims Afro-Indigenous Spirituality Beyond Fable Or Mythology

Writing flows through Akwaeke Emezi like water. By 7 years old, they read through all of the books in their parent’s house.

“I started writing when I was 5, at the same time when I started reading,” they said in a recent interview. “Reading and writing were always hand in hand for me.”

The Nigerian author originally moved to Boston to attend Tufts University for veterinary medicine in 2013, but soon realized the field wasn’t for them. “Although the pets are your patients, the people are your clients.”

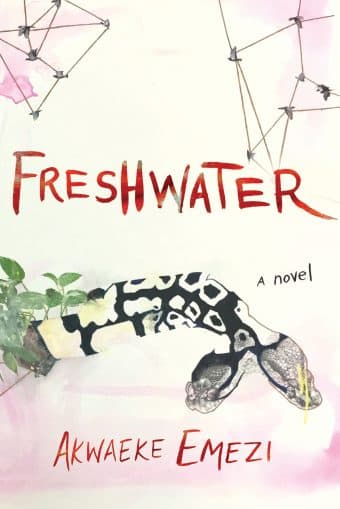

After leaving the veterinary field behind, they applied to the MFA program at Syracuse University. In two semesters, Emezi wrote what became their debut novel “Freshwater.” They’re slated to delve into the novel, and other works, at MASS MoCA on Thursday, Oct. 11.

A New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice and longlisted for the Brooklyn Public Library Literary Prize, “Freshwater” is teeth and warmth and worship, all at once. It’s a semi-autobiographical tale, an emotional cyclone centered around Emezi’s own realities unearthing their identity as a being that is more than just human flesh. Emezi’s experiences of being transgender and being “a spirit customizing its vessel to reflect its nature” inform portions of the plot of “Freshwater.”

Ada, the novel’s main character, is not the only one in her body. She shares it with other identities called the ogbanje, beings from Igbo ontology who are not supposed to be born into human flesh. This dissonance takes Ada into some dark, deep places, from self- harming to the loss of friendships and relationships to loss of self — spaces and experiences Emezi describes in razor detail. Ada is essentially a god “stuffed into a bag of skin” and after a traumatic experience, the other identities begin to assert more autonomy.

While some book critics and reviewers have interpreted the novel as an allegory for mental illness, Emezi pointed out that the problem with Ada is not the ogbanje or the things that have happened to her. “It’s because she’s embodied,” Emezi emphasized.

“The premise of the ogbanje ... is that you’re supposed to be in the spirit world.” With “one foot on the other side,” Ada eventually migrates from Nigeria to America. Her journey, filled with loss, leaves one emotionally bruised or pulsing with sad familiarity.

The inclination to label “Freshwater” as a novel about mental illness, in many ways, erases the legitimacy of Igbo spirituality. “I don't think there's a common or popular understanding of indigenous faith tradition[s] being valid philosophies,” Emezi said. “Or being lenses through which we can process things.”

Afro-indigenous religions and spirituality play a seminal part in African and Afro-diasporic cultures. However, colonialism and weaponized syncretism severely reduced the number of those openly practicing Afro-Indigenous religions.

In this light, the radical nature of “Freshwater” is clear. It demands to be read as reality — not as fable or mythology served to juxtapose Christianity. In order to truly hold it close, one must be willing to accept the realness of Ada’s experiences, experiences based on Emezi’s.

Centering Afro-indigenous spirituality has traditionally been a tool of resistance against white supremacy, a tool that white supremacy has tried to extinguish since colonialism reached its hand into the African continent.

“White supremacist realities have been invested in erasing African and indigenous realities,” Emezi pointed out. “At a certain point, realities can’t coexist if some are actively trying to erase the others.” Emezi’s work stands in defiance of these constant attempts of erasure.

Asserting Igbo spirituality as reality is part of the decolonization process. Igbo ontology is about more than “folklore and superstition,” Emezi said. It is a way through which one can interpret physics or science or spirituality.

Colonialism’s hand has heavily influenced how we shape our realities but the reclamation of Afro-indigenous ontology and staking it as truth can be the beginning of an individual’s spiritual revolution.

Akwaeke Emezi is already working on their forthcoming second novel “The Death of Vivek Oji,” which is also set in a bustling Nigerian community.