Advertisement

In A Rapidly Changing World, 'The Little House' Endures

“Once upon a time, there was a little house, way out in the country." So begins Virginia Lee Burton's beloved picture book "The Little House." Published in 1942, it won the prestigious Caldecott Medal and was even adapted into a Disney short.

Even if you're not from New England, chances are you know Burton's work. The Gloucester artist authored many popular children's books, including "Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel" and "Maybelle the Cable Car," and founded the Folly Cove Designers, an influential mid-century textile collective. Burton achieved perhaps her greatest acclaim with the "The Little House," which was published in 1942. A new exhibition about the book debuted last year in Japan, and recently arrived at the Cape Ann Museum in Gloucester.

The titular character of "The Little House" is a delicate shade of pink, with a pair of windows that look like eyes. She sits alone on a hill surrounded by fields and farmland. Soon, roads arrive, followed by apartment buildings and trains, until the little house is surrounded by skyscrapers and can no longer see the stars. In the end, a crew of movers comes to the rescue, lifting the little house onto a truck trailer and transporting her back to the country.

Cape Ann Museum curator Martha Oakes says the story offered comfort to readers when it was first published during World War II, and 12 years later, when it became popular in post-war Japan.

"A book like this ... shows that even if perhaps the worst thing in your life happened, that your house got swallowed up by the big city, [that] time can go on and you can recover," Oakes says.

Today "The Little House" can be read as a warning about the human threat to the environment, or the impact of urbanization on modern life. These are familiar anxieties for Gloucester residents, who worry that the area's rural charm is disappearing.

"Everybody has a home," says Cape Ann Museum director of education and public programs Courtney Richardson. "It might not look like a house, but we all have this place that is special to us, and if we think about that changing, I think that's a real fear."

Virginia Lee Burton's old neighborhood in Gloucester has, for the most part, withstood the tides of change.

That's according to the author's nephew, Sandy Burton. (Burton is sometimes referred to in the press as Ross Burton — Sandy is a nickname.) Standing by the side of a road near the northernmost tip of Gloucester one rainy afternoon, he points across an inlet to a rocky strip of land. "Right here, at the end of Folly Point, is where Virginia Lee Burton had her writing cottage," he says.

Advertisement

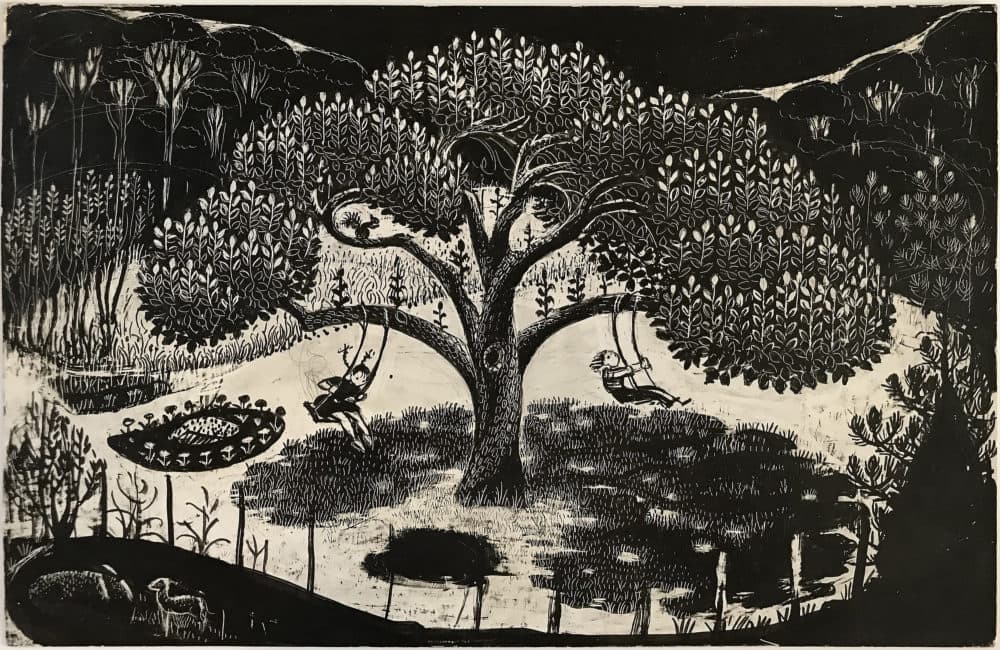

The writing cottage has since been moved, but the barn where Virginia Lee Burton taught printmaking still stands. From the late '50s until her death in 1968, it was the homebase for the Folly Cove Designers. The group, which was made up of locals who took Burton’s printing classes, was renowned for its exquisite wood block prints.

Ninety-three-year-old Lee Steele remembers how Burton taught them to refine their designs through painstaking repetition.

"[Burton] was extremely disciplined," Steele says. "She had a sign on her door saying, 'Do not disturb before 2 p.m.' And she worked all morning."

The exhibition at the Cape Ann Museum reveals Burton’s meticulous process, and her talent for capturing the beauty of the natural world. It also nods to the feminist undertones in Burton's work, where female protagonists, like the little house, abound. Those characters reflected Burton's own personality.

"She was vital. She was powerful, in her way," Steele says. "And she was fun, at the same time."

Steele remembers Burton’s house — where she lived with her husband, the artist George Demetrios, and their two sons — as the scene of neighborhood barbecues and dances. That house is still here, just a short walk down the street from the barn. It’s tucked back, shifted from its original spot by the road, much like how the little house in Burton’s book was moved from its first home.

As she squelches up the muddy driveway, Steele gestures toward the front yard. “This was all sheep pasture," she says.

Now that sheep pasture is full of trees. But the house, with its narrow, lopsided roof, looks how it always did. Really, Steele says, it’s hardly changed at all.

This segment aired on November 21, 2018.