Advertisement

Study Shows Spending For Drug Marketing Skyrocketed Over Past 2 Decades

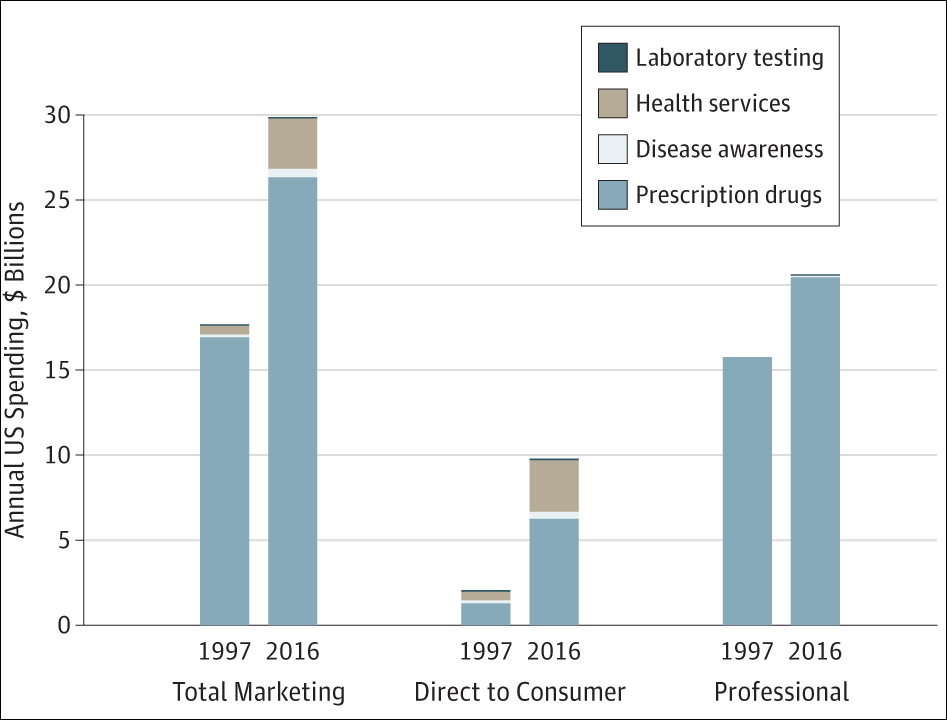

A new study released Tuesday found that spending on medical marketing significantly increased over the past two decades, going from $17.7 billion in 1997 to $29.9 billion in 2016.

The study, in the Journal of the American Medical Association, was co-authored by Dr. Steven Woloshin and his late wife, Dr. Lisa Schwartz.

Here's our conversation, lightly edited, with Dr. Woloshin, professor and researcher at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, on Radio Boston:

Callum Borchers: So tell us, if you would, about the key findings of this study that you're just publishing today.

Steven Woloshin: Well, the main finding is what you just said— there's been this enormous growth in marketing of medicine in the United States. So approximately $30 billion in 2016 is a pretty big number. I mean, that's more than the total budget of the National Institutes of Health. It's six times the total budget of the FDA, and they have to regulate food, medicine and tobacco. So it gives you an idea of the enormous investment that the companies are putting into promoting things. And as you said, the most rapid increase was in direct consumer advertising for corruption drugs and health services. But the biggest amount of money still is advertising to health professionals. So detailing visits — that's where the drug companies send representatives to doctors offices to ostensibly teach them about drugs — and then free samples, which are given to make them available to patients.

CB: We'll talk a little bit about that in a minute, but I want to start with the direct-to-patient advertising that you mentioned off the top, because it was the biggest percentage increase. You found it was about $2 billion in 1997, almost $10 billion in 2016 — so about a five-fold increase. What does that tell us about how drug companies are targeting patients, and what concerns do you have about it?

SW: You're right. It tells you that patients really are the focus. And it makes sense, because direct-to-consumer marketing works. There is evidence that it increases patients' requests for drugs and that they get prescriptions for the drugs that they request. This is for advertised drugs, even if there are lower-cost alternatives available. It reflects this general increase in the consumer movement: the idea that we're empowering consumers by presenting them with treatment options, so direct-to-consumer advertising sort of plays into that. And it's important because it bypasses doctors and health systems who might want to practice more conservatively. But the patients now are being encouraged to request these new and more expensive drugs.

It also reflects general issues that are pushing medical marketing, both [for the] professional and consumer. Things that are creating larger and larger reservoir patients — so scientific advances, which mean that there are more effective treatments. So now, once failed diseases are now chronic illnesses, or an increased interest in prevention and in aging and more insured population now with Medicare Part D and the Affordable Care Act. And finally, just the economics of healthcare. There's more and more consolidation and growth of the for-profit sector, and they're competing for patients, so they need to reach these patients, and that's just driving marketing.

CB: I wonder, though, if there can be an upside. And, I should point out that there are some important disclosures in these ads as well. As they say, you should talk to your doctor if you're having this symptom or that symptom. They do give you fair warning, like this:

Ad Compilation: "Allergic reactions such as shortness of breath or swelling of tongue and throat may occur and be fatal... vivid or unusual strange dreams ... decreases in white blood cells, which can be fatal, dizziness, seizures ... if you experience any of these behaviors of reactions, contact your doctor immediately. Wake up ready for your day. Ask your health care provider."

CB: So Dr. Woloshin, are you satisfied by those disclaimers, and can there actually be an upside to the marketing, which is that maybe we're creating a more informed patient group that doesn't just rely on doctor knows best? Maybe they can ask better questions and advocate for themselves?

SW: That's an interesting point. To be fair, not all direct-to-consumer marketing is bad. There's evidence that it can reduce underuse of treatments, but it also increases overuse of treatments, as well. It's a mixed bag. I think that you're being a little too generous with the effects of those disclaimers on educating patients. The first thing I'd say is those statements are not quantified, so you don't know how often these things happen. There are these long laundry lists that people tune out. I think the most important thing is, as a patient, how am I supposed to interpret these things when I don't know how well the drug works? The ads almost never tell you how well the drug works, and people tend to assume that they'll work really well for everyone, and that's just wrong.

CB: We've heard from other physicians, as well, that it can be hard when they feel some pressure when a patient comes in and specifically asks about a certain drug or a certain treatment. This summer, we spoke with Dr. Elisabeth Poorman, who is a primary care doctor in Everett. She's also an instructor at Harvard Medical School, and she talked about just that scenario, when an infected patient comes in and asks a physician like her, "Hey, I'm interested in this drug."

Recording of Dr. Elisabeth Poorman: "In America, medicine is a business, and we haven't approached what does that mean for individual physicians. How do you make the right ethical choice for your patient when actually you are a business conduit, right? There are people who are trying to sell these devices, drugs, surgeries and treatments, who spend all day thinking about how to promote their product even if the science isn't really there."

CB: Dr. Woloshin, can you relate to that in your own practicing? Do you have patients come to you and say, "Hey what about this drug? I saw an ad for it," and how do you deal with that?

SW: Sure. I practiced for many years and I had many patients come to me, and that's one of the reasons why [Dr. Lisa Schwartz] and I developed this thing called the drug facts box, which is a way to summarize drug information — the benefits, harms and uncertainties of a drug, using the same information that the FDA used when they decided to approve the drug. So the idea is to let people know what the FDA knew.

That's information — that's different than a drug ad, which is not talking about benefit, which people assume is there, so it magnifies benefit. [The ads list] side effects and long, un-quantified laundry lists, so that minimizes the harms and doesn't acknowledge uncertainties. The drug ads are really effective in the sense that people pay attention to them and maybe they know the names of the drugs, but as far as a vehicle for educating people and promoting informed decision-making, I think they're pretty useless.

CB: To your earlier point, there is also the marketing to physicians. In fact, there was another study published just a couple of years ago in the Journal of American Medical of the American Medical Association that showed as little as $20 in free food from a pharmaceutical company could actually influence physician's prescribing habit. This is the scenario that you were talking about, Dr. Woloshin, where you have maybe a lunch ostensibly to inform a doctor about a new treatment therapy. So I wonder how you handle that, and what can the medical profession do about it, because as you mentioned, the FDA is stretched thin. There's perhaps not enough people to do the oversight.

SW: You're raising a really important issue, and I think it might be interesting to talk about in the context of the opioid crisis. We're all so familiar with this tragedy that, in part, was caused by exactly that sort of marketing — that the companies paid thousands and thousands of physicians, pharmacists and nurses to attend speaker training conferences, and they sponsored more than 20,000 education programs. They sponsored these ostensibly scientific organizations like the American Academy of Pain Medicine and the American Pain Society — substantially funded by the opioid manufacturers — but they issued statements endorsing the expanded use of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain, and asserted addiction risk was low, which wasn't true. And sadly and inexplicably, the FDA allowed that kind of language into the label. The companies also deployed an army of drug reps to go on the detailing visits to meet with doctors in their offices to promote opioid prescribing. The detailing visits accounted for one of the biggest categories of marketing, over $5 billion bucks in 2016. FDA can monitor the print and television ads, but they have no way to monitor what goes on in these encounters, or the drug company dinners, or the training programs to push their agenda. And that's a recipe for disaster. In the case of the opioid crisis, prescriptions and sales quadrupled between 2000 and 2015, and so did deaths.

CB: Dr. Woloshin, you co-authored this study with your late wife, Dr. Lisa Schwartz. She passed away from cancer in November; please accept our condolences. I know that you worked on a lot of things together, from lobbying the FDA for the drug fact box that you talked about, and I just wonder how you're feeling now that the study has been published knowing this was such a big collaboration for the two of you.

SW: We worked on this paper for almost two years. I'm very proud of the work that we did, and it's very bittersweet, because it's extremely sad and hard for me to even talk about it because the loss is so devastating. Everything I know about these issues that we've been talking about, I learned with her or from her. The only reason I'm here today is really because she believed so strongly that medicine was being corrupted by marketing, and she wanted to do what she could to help people make good decisions and get them the information they need that hasn't been influenced by people trying to sell something. So, I'm really proud of the work. I'm really happy that the journal published this beautiful tribute to her. It means a lot to me. But I'm just devastated.

CB: It's an important legacy. We appreciate your sharing it with us.